Perhaps due to poetic license, or historical media hearsay (i.e. inaccuracies that become “fact” due to continuous repetition in TV, movies, and literature), the second season of Downton Abbey shows a largely abbreviated and fictionalized version of life in a country estate-cum-military hospital. Sue Light, a British Military Nurse historian and blogger at This Intrepid Band, posted about the inaccuracies here and here to clear things up (and her blog does not diminish my enjoyment of the series!). Since there are many historians and genealogists with far, far greater knowledge of WWI nursing and military hospitals, my post is to give a general overview of the topic–within the context of the show–during the Great War, using the primary and secondary resources I have on hand.

In August 1914, there were “463 trained nurses of Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Nursing Service (QAIMNS), and of the Territorial Force Nursing Serving 2783…the British Red Cross, St. John’s Ambulance Association and Brigade, and the County Associations (men and women) numbered 2354.” Nurses were needed at once, and six parties of QAIMNS reserves were sent to France and Belgium by August 20th, the Naval Nurses (about 70 in reserve) were called up and sent to various hospitals, and the Territorial force were called out on August 5th, “and in ten days 23 Territorial General Hospitals in England, Wales and Scotland were ready to receive the wounded and the nurses were also ready.” Each of these Territorial General Hospitals had 520 beds, but this soon proved inadequate after a few months of war, and “the accommodation of practically every hospital was increased to 1,000 to 3,000 beds and many Auxiliary Hospitals had to be organized.”

Galvanized by the same calls for patriotism and bravery as their menfolk, ladies of the upper and aristocratic classes were eager to do their bit by volunteering as nurses and lending their estates to the military–all of which caused considerable chaos amongst the trained nursing corps and the Government. The young ladies like Lady Sybil Crawley, or her real life counterparts Joan Poynder (dau. of Sir John Dickson-Poynder) and Monica Grenfell (dau. of Lord Desborough), war work combined their desire for independence and to have something to do.

Joan Poynder had a “passion for independence…and I knew that I wasn’t going to get much in the pre-war days except through marriage…But luckily I got it immediately by pretending I was much older and going in for nursing.” By lying about her age, Joan was able to join the Red Cross, and “after a period of nursing in six hospitals in England, managed to get into a French hospital, even though at nineteen she was below the regulation age for such work.” Monica became a probationer at the London Hospital in August 1914, and three months later was accepted as probationer at the British Hospital at Wimereux, where she was the only one amongst a fully trained nursing staff.

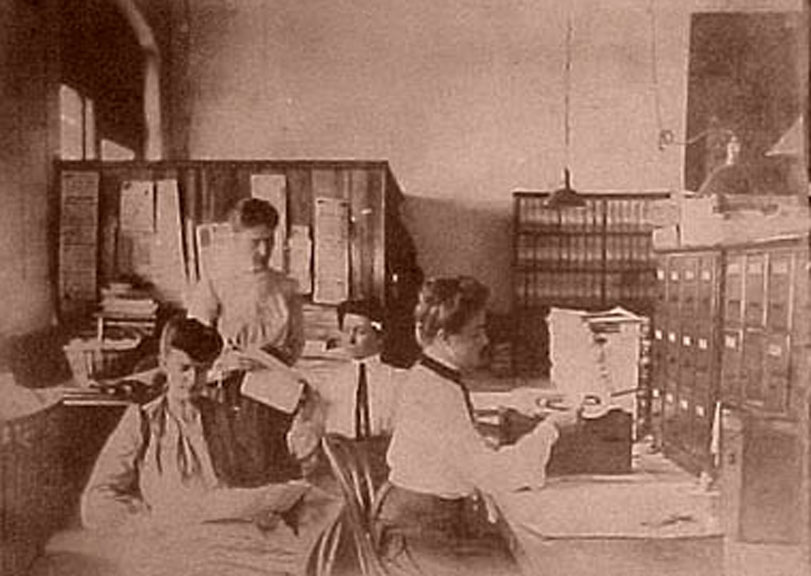

THE VOLUNTARY AID DETATCHMENT (VAD) DURING THE FIRST WORLD WAR © IWM (Q 2469)

The British Red Cross and the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, worked together through the joint committee set up to administer the Times Fund for the Red Cross, and in time of war they were controlled by the War Office and Admiralty. The Red Cross had, since 1909, “organized Voluntary Aid Detachments to give voluntary aid to the sick and wounded in the event of war in home territory. There were 60,000 men and women trained in transport work, cooking, laundry, first aid and home nursing. St. John’s ambulance had the same system of ambulance workers and V.A.D.’s to call on.”

The services of V.A.D.’s–many of them from good backgrounds and with little nursing service, let alone experience in a professional capacity–were soon depended upon heavily, as it became quite clear within the first weeks of the war, that the number of trained nurses, both veteran and recent graduates, provided inadequate. V.A.D. Hospitals were opened, most of them in large private houses lent for the purpose, and within “nine months there were 800 of these at work in every part of England, Scotland and Wales.”

Vera Brittain, who left Somerville College to join the V.A.D. in 1915, wrote to her fiance, Roland Leighton:

I can honestly say I love nursing, even after only two days. It is surprising how things that would be horrid or dull if one had to do them at home quite cease to be so when one is in hospital. Even dusting a ward is an inspiration. It does not make me half so tired as I thought it would either…

The majority of cases are those of people who have got rheumatism resulting from wounds. Very few come straight from the trenches, it is too far, but go to another hospital first. One man in my ward had six operations before coming and is still almost helpless…

I have various things to do, all of which belong to the kind of work which is called probationers’ work. Another nurse & I have three wards to look after between us. Generally I do two & she does one, as she has other work like massage to do which does not come within my sphere. I have to take the men their breakfasts (they are nearly all in bed for breakfast), prepare the tables for the doctor, with hot water etc, tidy up & dust the wards & make the beds. These latter are not made in the ordinary way but in a particular method you have to learn how to do, & are called medical beds. Not every sick person has a medical bed, but cases of rheumatism always do.

Many V.A.D.’s wrote of their experiences with hostile Sisters, who despised them for not being properly trained, and “Matrons of ordinary hospitals, accustomed to a rigid system, found it difficult to handle voluntary workers, whom at first they distrusted. Class feeling also came in, and for a while in some hospitals the voluntary help did not work well.” No doubt the frivolous actions of V.A.D.’s like Lady Diana Manners, who while nursing at the Rutland Hospital (her mother, the Duchess of Rutland’s town home, converted to an officer’s hospital), spent much of her off-duty time partying into the early hours of the morning, contributed to this feeling, but for the most part, V.A.D.s proved themselves, and earned the grudging respect of trained nurses.

Caption of Punch’s satirical cartoon: Visitor. “And how did you know when you were wounded?” Tommy. ‘Saw it in The Daily Mail.”

Over the course of the war, numerous country estates and London mansions were converted into hospitals and convalescent homes for military casualties or as temporary lodgings for the scores of Belgian refugees who escaped their occupied country in 1914. At the Duke of Bedford’s Woburn Abbey, the riding school and indoor tennis court were converted into a 100-bed hospital, and Blackmoor, the Hampshire home of the Earl and Countess of Selborne, was converted with the countess as commandant, and the drawing room, dining room and smoking room turned into wards, the hall into the men’s living room, the library as the nurses’ sitting room, and the billiards room became a store (not until Easter 1919 was the home turned back to its pre-war appearance). Even Highclere Castle was converted to hospital use, with the Countess of Carnarvon turning to her (rumored) biological father, Alfred de Rothschild for funds with which to equip her home with the finest service.

According the present Lady Carnarvon in an article in The Telegraph:

Thirty nurses were recruited. The family’s personal physician was hired as medical director. Arundel, a bedroom on the first floor in the northwest corner of the house, became an operating theatre. All the castle’s 41 south-facing rooms had to be fitted with exterior blinds. And when the men started to arrive, “it was like moving a house party of 50 people into the castle on a permanent basis” – with the same number of staff. [Source]

Not all estate owners were as generous: Lord Wemyss declined his wife’s suggestion to turn Stanway into a hospital, and even threatened to close the house altogether! This reaction was rare, however, and both nurses and owners of great estates experienced many traumas and hardships on the Home Front, which did much to shake up Edwardian society.

Sources:

Ladies of the Manor by Pamela Horn

Women and War Work by Helen Fraser

How We Lived Then, 1914-1918 by Mrs. C. S. Peel

Testament of Youth by Vera Brittain

Women in the First World War by Neil Storey

Further Reading:

Country Houses in Medical Service – Jane Austen’s World

The Military Hospitals at Home

World War One: wounded soldiers and the Edmonton Military Hospital

Auxiliary Hospitals During WWI

What did the Red Cross do in WWI?

Letters home from a First World War nurse

The role of aristocratic volunteers during the First World War

Fabulous post. Thank you for this wonderful information, which I shall be linking to. Vic