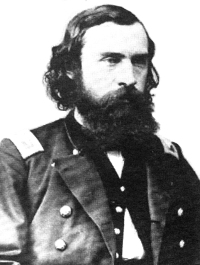

Outside of a financial panic or murder, the only thing that struck fear into the hearts and minds of Gilded Age society was Town Topics. This elegant weekly, which recorded the exploits of society, published promising literature, sporting news, and even offered financial advice, was published by Colonel William d’Alton Mann, a Civil War veteran and businessman, who developed a railroad sleeping car before selling it to Nagelmackers (of Orient Express fame) in 1883. Between this time and his acquisition of Town Topics, Mann had made and lost a fortune warring with George Pullman, but through his various failures he quickly realized the fortune to be made in society gossip.

Outside of a financial panic or murder, the only thing that struck fear into the hearts and minds of Gilded Age society was Town Topics. This elegant weekly, which recorded the exploits of society, published promising literature, sporting news, and even offered financial advice, was published by Colonel William d’Alton Mann, a Civil War veteran and businessman, who developed a railroad sleeping car before selling it to Nagelmackers (of Orient Express fame) in 1883. Between this time and his acquisition of Town Topics, Mann had made and lost a fortune warring with George Pullman, but through his various failures he quickly realized the fortune to be made in society gossip.

Town Topics began its life as The American Queen, and under editor Louise Keller (founder of the Social Register), it was a genteel periodical dedicated to “art, music, literature, and society.” The failing magazine was purchased by E. D. Mann, the Colonel’s brother, who renamed it Town Topics and began to change the tone from one of polite obsequiousness to fit the new era of celebrity culture ushered in by social climbing swells like the Vanderbilts. E.D. Mann handed control of Town Topics to the restless Colonel Mann, who pushed the magazine into infamy.

The Colonel, whom acquaintances described as “a kindly looking gentleman,” soon gathered a network of paid spies drawn from servants, telegraph operators, hotel employees, seamstresses, grocers, and vengeful socialites to supply the magazine with gossip. He created a column for these juicy scandals entitled “Saunterings,” where he planted them between seemingly innocuous descriptions of the latest social events in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston. Anonymous gossip was nothing new to society journalism, but Colonel Mann turned the tables with “Saunterings” by scattering clues about the subject of his “blind items” throughout the harmless society news. And sometimes, he was bold enough to state the persons involved in the scandal outright.

The Colonel, whom acquaintances described as “a kindly looking gentleman,” soon gathered a network of paid spies drawn from servants, telegraph operators, hotel employees, seamstresses, grocers, and vengeful socialites to supply the magazine with gossip. He created a column for these juicy scandals entitled “Saunterings,” where he planted them between seemingly innocuous descriptions of the latest social events in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston. Anonymous gossip was nothing new to society journalism, but Colonel Mann turned the tables with “Saunterings” by scattering clues about the subject of his “blind items” throughout the harmless society news. And sometimes, he was bold enough to state the persons involved in the scandal outright.

An example after the jump:

Society News

At the Patriarchs’ Ball it was noticed that Ward McAllister devoted himself almost entirely to Lady Sykes, and I hear that he made himself familiar, through his repeated questioning of Lady Sykes, with the proper way of addressing Royalties and English swells in general…Blind Item

High society has been treated to a sorry spectacle of inebriety during the last two weeks at balls and dinners, and I am glad to say that this shocking example, though unfortunately a woman, is not an American, but a specimen of British aristocracy. Society, far from endeavoring to shield her failings, has been openly discussing her behavior at the dinner party given in the house of one of the newly rich swells of New York, and has freely commented on her calling for a “B&S” (Brandy and Soda) during the progress of the cotillion at one of the most recent balls. If Great Britain is to send us such specimens of her boasted aristocracy, I would advise society to entertain in camera and with a bread and water diet. Clue.

The rise of Town Topics created chaos with American High Society. Socialites and plutocrats knew not which way to turn, suspecting their housemaids, butlers, and dressmakers of supplying the gossip, or even their social enemies. The threat of in-home spies made society so paranoid, many began making up gossip to test the trustworthiness of their servants and circles. Yet, Town Topics was the most widely-read magazine in society–though no one would ever admit to owning a subscription. Colonel Mann quickly upped his bribery to outright blackmail, offering those guilty of indiscretions the opportunity pay for the suppression of certain facts. If a story was particularly damaging, Mann would print up a copy Town Topics and send it to the offender to allow them to correct any errors. On the days before Town Topics went to press, worried members of society arranged meetings with Mann at his favorite place–Delmonico’s–, or in his office, where they could negotiate for discretion. The amounts Mann managed to extort from America’s wealthiest men was staggering ($10,000 was about $230,000 in 2008 dollars):

E. Clarence Jones, $10,000

Russell Alger, Senator, $100,000 in Alger-Sullivan Lumber Co. shares

William K. Vanderbilt, $25,000

Dr. Seward Webb, Vanderbilt’s brother-in-law, $14,000

William C. Whitney, $1,000

J. Pierpont Morgan, $2,500

George Gould, son of Jay Gould, $3,000

Howard Gould, son of Jay Gould, $2,500

Collis P. Huntington, $5,000

James R. Keene, $76,000 (+14,000 repaid !)

John ‘Bet-a-Million’ Gates, the barbed-wire king, $20,000

Roswell Flower, broker & former governor of New York, $3,000

Grant B. Schley, $1,500

Charles M. Schwab, $10,000

Thomas Fortune Ryan, $10,000

Perry Belmont, $4,000

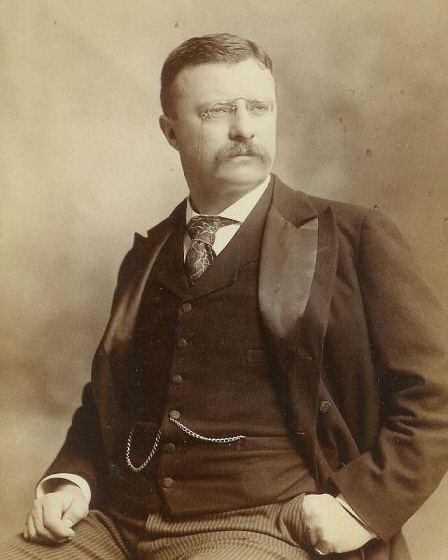

Ironically, Colonel Mann’s downfall came not from his extortion racket but from his 1904 attack in “Saunterings” on the willfully scandalous Alice Roosevelt.

From wearing costly lingerie to indulging in fancy dances for the edification of men was only a step. And then came—second step—indulging freely in stimulants. Flying all around Newport without a chaperon was another thing that greatly concerned Mother Grundy. There may have been no reason for the old lady making such a fuss about it, but if the young woman knew some of the tales that are told at the clubs at Newport she would be more careful in the future about what she does and how she does it. They are given to saying almost anything at the Reading Room, but I was really surprised to hear her name mentioned openly there in connection with that of a certain multi-millionaire of the colony and with certain doings that gentle people are not supposed to discuss. They also said that she should not have listened to the risqué jokes told her by the son of one of her Newport hostesses.

Norman Hapgood, editor in chief of Collier’s Weekly, a popular magazine whose founders were viciously attacked by Mann, used this opportunity to openly attack Town Topics and its creator. Mann fought back in his own editorials, but Hapgood threw down the gauntlet and charged Mann with blackmail. Matters escalated–as Hapgood wanted–until Mann sued Collier’s and Hapgood for libel. The trial, which opened January 16, 1906, laid the inner workings of Town Topics bare, and it took the jury minutes to find Hapgood innocent of libel. The DA’s subsequent charges of Mann for perjury started another circus, and though the Colonel cleared of the charges Town Topics never again held society in abject fear and terror. The magazine limped on until shortly after Colonel Mann’s death in 1920, but he had changed the way newspapers and magazines reported gossip for good.

Further Reading:

The Man Who Robbed the Robber Barons: The Story of Colonel William d’Alton Mann by Andy Logan

A Short History of Rudeness: Manners, Morals, and Misbehavior in Modern America by Mark Caldwell

A Season of Splendor: The Court of Mrs. Astor in Gilded Age New York by Greg King

He was the Rupert Murdoch of his time!

Lol, totally.

Bizarre, I had left a comment but it didn’t take. I had read somewhere that Emily Post’s husband’s refusal to succumb to Mann’s blackmail led partly to his downfall.

It was. Edwin Post, Emily’s husband, colluded with the D.A. William Travers Jerome to set up a sting to bring Mann down about a year after Town Topics attacked Alice Roosevelt.

This is the most telling line: “Town Topics was the most widely-read magazine in society–though no one would ever admit to owning a subscription.” People always seemed to love dirt being dished on tall poppies, and probably haven’t changed in the last 100 years. But they were embarrassed by their _own_ nastier, gossipier side.

The amounts Mann managed to extort from those very wealthy families was nightmarish. You correctly labelled “negotiating for discretion” as what it was – blackmail. The sad thing is that if my sons were drinking in public or my husband was giving dictation to the secretary every night of the week, I might be desperate too. People get into a total panic when their good name is/might be tarnished, a fact Mann absolutely understood.

We had a newspaper in Melbourne that flourished for decades. Apparently it made so much money by negotiating for discretion with desperate families, there was no need for paid advertisements in the paper!

The love/hate relationship we have with gossip fascinates me. I freely admit to finding celebrity gossip entertaining, so I’m always amused by the number of people who leave comments like “who cares?” or “aren’t there more important topics to discuss?”.

The prospect of scandal seems to be the zeitgeist of the Gilded Age, which is interesting when compared to England and Europe (sans France), where the scandals were mostly suppressed with the tacit collusion of the press. Perhaps the exposure of scandal by journalists is/was a unique function of a republic–freedom of press, transparency, etc.

You brought up an interesting point Evangeline. The US papers, particularly those owned by Hearst, began during the Gilded Age to become more and more salacious (yellow journalism) whereas in England, they were much more discreet. The affair between Edward VIII and Mrs. Simpson wasn’t really reported on until after he became King and it looked like it was moving towards marriage.

It’s also very interesting to read issues of Country Life and Town & Country from the 1900s. Though both focus on the aristocracy of Britain and America, respectively, there’s a sort of apologetic and kowtowing tone in CL towards the British aristocrats who opened their homes to its journalists, whereas T&C presents upper-class life as something its readers have a right to know about and aspire to joining.

That certainly hasn’t changed in the past 100 years either, although The Tatler spends a great deal of time both fawning and poking fun at the aristocracy.

I really need to subscribe to the Tatler, or at least browse through a copy!

Has anyone ever seen Muller-Ury’s 1902 portrait of the Colonel?