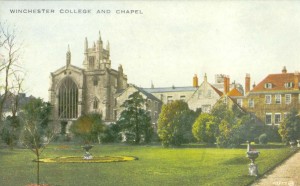

Winchester is older, Rugby the most progressive, and Harrow boasts the most illustrious alumni, but when one thinks of the English public school, one thinks of Eton. Located near Windsor, almost in the shadow of the eponymous Royal Castle–which no doubt showered the college with royal favor–Eton came to symbolize all that was right and good with Edwardian England. Eton was founded by Henry VI in 1440, who drew the rules for governing this “college” from that of Winchester’s, and even took half of that college and settled them at Eton.

Winchester is older, Rugby the most progressive, and Harrow boasts the most illustrious alumni, but when one thinks of the English public school, one thinks of Eton. Located near Windsor, almost in the shadow of the eponymous Royal Castle–which no doubt showered the college with royal favor–Eton came to symbolize all that was right and good with Edwardian England. Eton was founded by Henry VI in 1440, who drew the rules for governing this “college” from that of Winchester’s, and even took half of that college and settled them at Eton.

The new school was considered a sister college to its elder until it formed its own character (the aforementioned “royal favor”) and became the school of choice for the aristocracy and nobility. By the nineteenth century, Eton had educated more sons of the upper classes than the other public school, and its reputation as the birthplace of the empire’s brightest and highest in the land was solidified by the number of statesmen, military heroes, athletes, and writers, among others, who came out of the school.

Unlike at Winchester, the lines between Collegers and Oppidans, or the poor boys whose tuition and board were supplied by the college, and the boys whose parents paid for tuition and lived in their own houses with a Master, were fiercely drawn. The Collegers, no matter what form (grade in US English), were consigned to the worst food, lodgings, and treatment, and well into the nineteenth century, “the sixteen senior collegers had no water except what they made the lower boys fetch in for them overnight from the pump in the yard.” The lower boys had no basins or water at all, and they bore the brunt of the system of fagging, where “any neglect of duty was met with brutal punishment.”

This state of affairs, as well as the neglect and greed of headmasters, raised public outcry in the 1860s, and a Royal Commission was created in 1861, the effect of which was the Public Schools Act 1868, which “removed these schools from any direct jurisdiction or responsibility of the Crown, established church or government, establishing a board of governors for each school and granting them independence over their administration. The Act led to rapid development of the schools, away from the traditional classics-based curriculum taught by clergymen, to a broader scope of studies.”

Under the act and the statutes of 1872, neglect and abuse at Eton lessened, but they had the adverse effect of ridding poverty as one of the qualifications for admission. Now boys from wealthy and aristocratic backgrounds could enter Eton as Collegers. This broke down the prejudice against “beastly tugs”, yet it barred access to higher education of poor and lower-class boys, for whose attendance these public schools had been founded! Now a disadvantaged boy had to be extremely clever and intelligent to beat the well-to-do boys (whose parents could afford “crammers”) in the entrance examinations.

However, life at Eton could be exhilarating and stimulating. The guiding force of the boys were education, sports, and morals, though not always in that order, and independence of thought and a questioning outlook were encouraged. In School Boy Life in England: An American View, John Corbin presents a pleasant view of a typical Oppidan’s life:

However, life at Eton could be exhilarating and stimulating. The guiding force of the boys were education, sports, and morals, though not always in that order, and independence of thought and a questioning outlook were encouraged. In School Boy Life in England: An American View, John Corbin presents a pleasant view of a typical Oppidan’s life:

A boy enters his “house” at about twelve years old. From this time on he is carefully watched by the housemaster, with a view to checking his bad traits and developing his good ones. Most of the masters make it a point to find out all they can about a boy from his parents, and then carry on his training as it was begun; or if they think his training unwise, to correct it. The fact that most of the troublesome details of discipline are in the hands of the elder boys makes a master’s relations with his pupils unusually frank and affectionate. And as the masters are always well educated, usually sensible, and often famous athletes, they have a strong and very admirable influence. Much of all this, of course, the boy never suspects. He simply grows to respect and like his master without quite knowing why.

Perhaps the most important friendship a boy makes in his house is with his fag-master. His chief duties as a fag are to cook breakfast and supper in the house kitchen and serve it in his master’s room; but in many of the houses the boys eat all their meals together, except tea, which is always served in the separate rooms; so the fags have very little to do in return for the friendship of the older boys. In the past, to be sure, the system of fagging was often grossly abused; and even to-day it is, like all good institutions, liable to abuse; yet altogether too much has been said about its tyranny and brutality. Most small boys are glad enough to be with the big boys, and a Senior who plays football or rows well may have as many youngsters to wait on him as he chooses.

Fag-masters are often the fags’ best friends, and even at the universities afterwards keep a kindly eye upon them. Sometimes it happens that a fag turns out a great cricketer or oarsman, in which case his old fag-master is as proud of him as of a younger brother. Or, like as not, in after-life a country parson can look back upon the time when he fagged the bishop of his diocese. In a speech made in 1896 by Lord Rosebery, late Prime Minister of England, there is an amusing reference to fagging: “It is a long time since you and I, Mr. Chairman” (Mr. Acland, Minister of Education), “first met. I have always been a little under your presidence, because I began as your fag at Eton, and I little thought, when I poached your eggs and made your tea, that we were destined to meet under these very dissimilar circumstances.”

The Houses clustered around the college buildings were pleasant and cheerful. Unlike at Winchester, Eton boys had a room of their own, “seldom more than twelve feet square, and besides a folding-bed, bath-tub, and wash-stand, they contain not only a fireplace and a tea-table, but also a study table and chair, and sometimes a bookcase and an ottoman.” The boys spent most, if not all of their time, with the fellows in their house on a firm schedule of chapel, school hours, and “lock-up” in the evening. The result was that each house had its own debating society, cricket and football teams, and “house four” on the river.

The Houses clustered around the college buildings were pleasant and cheerful. Unlike at Winchester, Eton boys had a room of their own, “seldom more than twelve feet square, and besides a folding-bed, bath-tub, and wash-stand, they contain not only a fireplace and a tea-table, but also a study table and chair, and sometimes a bookcase and an ottoman.” The boys spent most, if not all of their time, with the fellows in their house on a firm schedule of chapel, school hours, and “lock-up” in the evening. The result was that each house had its own debating society, cricket and football teams, and “house four” on the river.

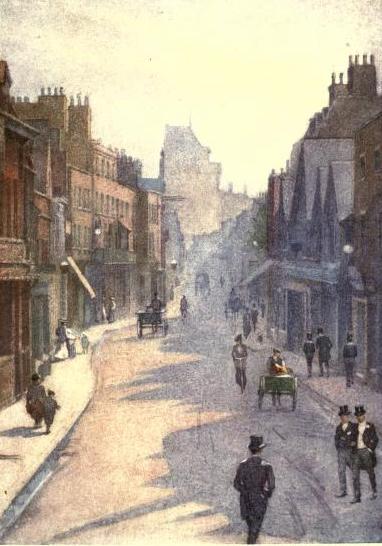

On an average full day, the Upper and Lower Schools were called to the two Winter Halfs at 6:45 am, and had to be in school by 7:30 (in the Summer Half this was 6:15 and 7 am). Hot coffee and cocoa and buns or biscuits were provided before Early School, which lasted fifty minutes, after which the boys returned to their houses for breakfast (8:20 in winter, 7:50 in summer). Chapel in winter and summer was at 9:15 and bells began at 9:50. After Chapel, which lasted about fifteen minutes, there was School until 10:30, and then an interval where refreshments were provided in the houses (though most boys would venture to the “Sock Shops” in town); School began again from 10:45 to 11:45.

From 11:45 till dinner (1:45 in winter and 1:30 in summer), or “after twelve,” Lower Boys went to the Pupil Room for exercises, verses, etc for their division masters, under the supervision of their tutor. They remained there until they finished and their tutor provided feedback (“tear them over” or “rip”, and if well done, exempted the student of needing to copy their verses, etc). This was also the time when troublesome pupils were disciplined. Dinner was mandatory unless given leave by the House Master, and after it until about 4 pm, Lower Boys were free to do as they like. They returned to School from 4 to 5:45, with a short break at 5 pm. After this was “lock-up,” and the boys had tea in their Houses, where an “Order” (bread, milk, tea and butter) was provided for each (this schedule changed depending on Sundays, Halfs, which school, and one’s academic standing, but otherwise).

Sports and school societies characterized Eton the strongest. The most important society was The Eton Society, or “Pop.” Exclusive, self-elected and wielding enormous influence over Eton, election to Pop was the most coveted social distinction at the college. In The Children of The Souls, Jeanne Mackenzie tells of the anxiety and struggle of Patrick Shaw Stewart, scion of an old, but financially-strapped Scottish family, and a Colleger, to get into Pop. Once inside this hallowed society, Patrick was taken up to the highest pinnacle of the social ladder by new friends Julian Grenfell, Charles Lister, and Edward Horner, among others, who were the children of the aristocratic and well-connected “Souls.”

Sports and school societies characterized Eton the strongest. The most important society was The Eton Society, or “Pop.” Exclusive, self-elected and wielding enormous influence over Eton, election to Pop was the most coveted social distinction at the college. In The Children of The Souls, Jeanne Mackenzie tells of the anxiety and struggle of Patrick Shaw Stewart, scion of an old, but financially-strapped Scottish family, and a Colleger, to get into Pop. Once inside this hallowed society, Patrick was taken up to the highest pinnacle of the social ladder by new friends Julian Grenfell, Charles Lister, and Edward Horner, among others, who were the children of the aristocratic and well-connected “Souls.”

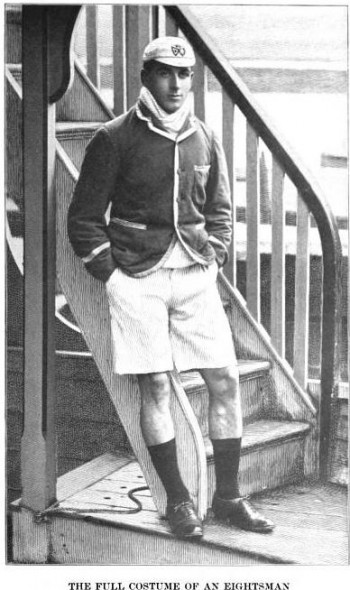

It is fitting that Pop, though wanting “first-rate fellows”, was filled with the college’s top athletes, for sports were the focus of all public schools during the Victorian and Edwardian eras. They were the cricketers who played against Winchester and Harrow, the boating-men who rowed for and often won the Ladies’ Plate at Henley, and the boys who represented the school at football. The Eton Wall Game, which was similar to rugby and football (soccer), pitted the Oppidans against the Collegers, fives were a favorite sport during the winter, and the annual cricket match between Harrow and Eton at Lord’s was so popular, it became a fixture on the social calendar from the 1870s on.

The height of the Eton calendar was the fourth of June, which celebrated George III’s birthday. On this day all Eton alumni visited the college, the boys’ mothers and sisters dressed in their finest summer gowns, and the Thames was filled with punts and house-boats:

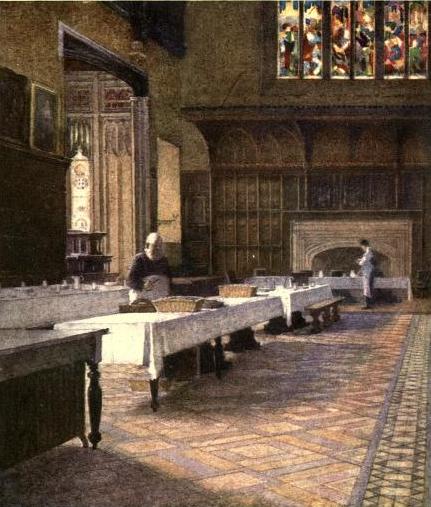

Luncheon is served in the College Hall, and after toasts are drunk all gather in the playing-fields to chat, listen to the music, and, perhaps, watch the game of cricket. At four o’clock comes chapel, and afterwards the boys serve strawberry-mess and tea to as many guests as can be got into their nine-by-twelve rooms. Then all the frocks, parasols, brass bands, white waistcoats, and buttonholes swarm to the river to celebrate the departure of the boats for Surly. This is conducted with almost military pomp. When the boats arrive at Surly, dinner is served under tents on the meadow opposite Surly Hall. After this they all row back.

Sources

School Boy Life in England: An American View by John Corbin

The Children of the Souls by Jeanne Mackenzie

Eton by An Old Etonian

The World and Its People v5 by Larkin Dunton

Eton: Water-colours by Edith Danvers Brinton

I’ve been waiting for this since forever. Thank you!!!

Glad to have been of service! And you’re welcome. 🙂

Wonderful post Evangeline. I hope you share with us more about the other schools, Winchester, Harrow and Rugby.

Thank you Elizabeth! I wrote a much shorter post and Winchester (and this post confirmed why there is so much information about Eton when compared to the other colleges!) last year.

I just adored reading this! Thank you so much, Evangeline!

I’m so glad this was enjoyable Valerie! You’re welcome.

This is the most detailed and benign description of the institution I’ve come across, and suggests an appetite for schedule and order that would have driven me barmy. For keeping adolescent boys out of trouble though, I suppose it had its charms. Thanks for a very informative post.

You’re welcome! I’m sure the headmasters and tutors appreciated the schedule. 😉

I love the watercolors! Where did you find them?

They are amazing, aren’t they? From the last book listed in my sources–it saved me a lot of time trying to find historical pictures of Eton.

Charming article and pictures…The book…Stand Before Your God…by Paul Watkins…gives a very interesting perspective by an American boy at Eton…Gracias for your fine blog…

What a wonderful post. I had always wondered what life was like at Eton. The pictures are beautiful too.

Wonderful post, Evangeline! A little bit of info for everyone! And I agree, the watercolors were gorgeous.

Do you have information regarding the Holland that Holland House is named for at Eton and the year it was named?