Among other pithy observations made by the Duke of Wellington, the most famous is the apocryphal boast that “The battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton.” Wellington attended the boys’ school during the late 18th century, and indeed, many of Britain’s most famous, most erudite, and most influential gentlemen passed through the halls of Eton, or Harrow, or Winchester, to name a few of the elite institutions. As England was and continues to be a class-conscious society, education was built on social lines, and even the public schools were divided into castes, with certain schools not only determining which set you belonged to, but also which college you would attend at Oxford or Cambridge.

The role of the public school played a large part in the creation of the ruling caste. Though English law regarded education as a right, irrespective of poverty, the access and leisure time required to commit to education has frequently been only in reach of those from the upper classes. The product of these public schools were leaders not only by birth, but by the careful and deliberate grooming of the headmasters. Their status as elite schools for gentlemen solidified after the Industrial Revolution, from which grew the plutocracy, and the emergence of the British Empire, which allowed the sons of younger sons of aristocrats the opportunity to earn a living whilst serving and protecting their nation–which in turn strengthened the ruling elites.

John Corbin, in his 1895 book, Schoolboy life in England, An American View, stresses the role in which public schools played in English society:

To be a public-school boy means as much in the afterlife as to be a college man means here [America]…a man may leave Eton or Rugby to go to the Military College at Sandhurst, to go into business, to travel–or to do nothing, in fact–and his case is easily explained; but if he wants to be sure of passing current among strangers he must at least have been to a public school–even if he has never passed an examination, was flogged every day of his life, and expelled at the end of his first term.

Because of this importance, a boy of eleven or twelve would be shipped off to Eton or Rugby from far-flung places of the Empire by his Colonial administrator father, and millionaire industrialists did all they could to get their sons into these schools. By the 1880s, it was even difficult for the sons of Old Wykehamists or Old Carthusians to obtain acceptance, as for example at Eton, the examination for Election tested candidates on Latin Composition (Prose and Verse); Translation from Latin and Greek; Mathematics (including Arithmetic, Algebra, and Euclid), and “General Papers,” not limited to Latin and Greek Grammar and Parsing. As attendance costs for these schools seldom fell below £100, each school set up a Foundation from which boys chosen for the scholarships could offset the steep fees. So fierce was the competition for the few slots which opened each year (ranging from eleven to fifteen in number), special tutors were paid upwards of 100-120 guineas a year (~$500-600) to drill boys as young as ten in the examination subjects.

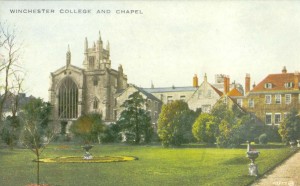

Of the public schools, the greatest were Winchester, Eton, Rugby, Harrow, and Charterhouse, with the first being the oldest existing public school.

Winchester was founded at the city of Winchester in Hampshire, England in 1382 by William of Wykeham, Bishop of Winchester and Chancellor to both Edward III and Richard II. Wykeham’s purpose in found his school, or “college,” as it has always been called at Winchester, was to prepare boys to enter a college he founded at Oxford (New College). So rigorous was the curriculum at Winchester, graduates found themselves too far advanced for the teaching they found at Oxford. Wykeham’s solution was to employ a special body of tutors at New College, a custom which spread to Oxford’s other colleges. This innovation influenced the structure of the English university system, whereupon each college had its own set of instructors. Wykeham intended that all his scholars should be chosen from the poorer people, and left funds to support them. These scholarships were highly coveted, and during the late 19th century, it was common for the sons of university graduates–who were often rich–to obtain these openings; far from the disadvantaged boys Wykeham intended. Within the college itself there was keen competition, particularly as the five or six best students were granted scholarships at New College (which was called “getting off to New”).

However, not all boys were supported by scholarships. Despite the difficult examinations and quest to become “scholar” of Winchester, there were boys who parents paid the full tuition, lodging, and board, which amounted to about £3500 ($700) a year. These boys were known as “commoners,” and though paying students did exist in the early years of the college’s founding they grew too numerous to control. In 1740, Dr. Burton, the Head Master, created the “Old Commoners” to serve the needs of non-scholar boys. However, their undisciplined behavior threatened the tranquility of the college, and Dr. Burton discharged the “commoners” to create the “tutor’s house system.” In each house resided about thirty-five boys, all of whom were under the care of the Master, whose family lived in as well.

Discipline at Winchester was not as strict as other public schools, but the boys–or men, as they were called–were not permitted to enter the town, and needed special “leave out” to go out and about the countryside. The typical school day began at seven in the morning, and bedtime was around nine or ten. Constant attendance at prayers were required, and there were four services on Sunday. For breaches of discipline, a boy would be flogged. However, the main idea of discipline in an English public school was that much of it should be dealt by the boys themselves. At Winchester it was ordained that eighteen of the older boys, called prefects, would “oversee their fellows, and from time to time certify the masters of their behavior and progress in study.” The duty of a prefect was to deliver a “tunding,” that is, beating a disobedient student across the back of his waistcoat with a ground-ash the size of one’s finger. According to an old Prefect of Hall, the art of tunding was to catch the edge of the shoulder blade with the rod, and strike in the same spot every time. In this way it was possible to cut the back of the offending boy’s waistcoat into strips.

All the public schools had their own customs and slang. At Winchester, a “strawberry mess” was a meal of strawberries and ice cream; a “horse-box” was a desk; and “washing stools” were the prefects’ tables, which were placed in commanding positions. A boy would ask of his cohort, “Is Smith a thick, or only a thoking jig?” which would translate as “Is Smith a blockhead or is he a clever boy who likes to loaf?” Each house would record the slang and customs in a book, in which all “notions“, ancient and modern, were recorded. A boy’s first duty, upon entering the school, was to pass an examination before his superiors on the contents of the book, whereupon he would be accepted, quite easily into the fold of the school–save if he were a complete rotter. In a way, the public school served as conditioning for the adult life of these boys, and was definitely the source of their love for pomp and tradition, and their unflagging devotion to “queen and country.”

Further Reading:

Schoolboy life in England, An American View by John Corbin

Everyday Life in Our Public Schools by Charles Eyre Pascoe

Winchester Notions: The English Dialect of Winchester College by Charles Stevens

School Life at Winchester College by Richard Mansfield