The typical Edwardian woman wished to see her name printed in the newspapers but thrice in her lifetime: at birth, at marriage, and at death. Fortunately for the press-hungry, a woman’s wedding was cause for pages and pages of articles devoted to announcements, details of the ceremony, and advice for the blushing bride. No more so was this seen than with the highly anticipated weddings of society women, whose trousseaux, bridesmaids, groom, and wedding gifts were newspaper fodder even for those invited! To regulate the demand for lavish weddings and press access to the impending nuptials, the already dozens of etiquette books on the market were supplemented by books devoted explicitly to pulling off a beautiful and unforgettable wedding ceremony.

The typical Edwardian woman wished to see her name printed in the newspapers but thrice in her lifetime: at birth, at marriage, and at death. Fortunately for the press-hungry, a woman’s wedding was cause for pages and pages of articles devoted to announcements, details of the ceremony, and advice for the blushing bride. No more so was this seen than with the highly anticipated weddings of society women, whose trousseaux, bridesmaids, groom, and wedding gifts were newspaper fodder even for those invited! To regulate the demand for lavish weddings and press access to the impending nuptials, the already dozens of etiquette books on the market were supplemented by books devoted explicitly to pulling off a beautiful and unforgettable wedding ceremony.

The wedding customs of Edwardian England heavily influenced the fashion in America, though there were considerable differences in the former. By the late 1900s, afternoon weddings had become very popular, with 2:30 pm as the most fashionable time, despite the legally recognized time for marriage ceremonies being between 8 am and noon.

To counteract this legality, a special license was obtained (during most of the 19th century, only a few were in position to obtain them) from the Archbishop of Canterbury, after application at the Faculty Office–though a very special reason had to be given to meet with his approval. This license cost on average about £30. Two other options for marriage in England were marriage by “banns” and marriage by license. The “banns,” from an Old English word meaning “to summon”, were the public announcement in church that a marriage was going to take place between two specified persons. They were required to be published in three consecutive weeks prior to the marriage in the parish in which the groom resided and also that in which the bride resided, and both bride and groom were advised to reside at least fifteen days in their respective parishes before the banns were announced.

A marriage by license was a bit quicker, as either the bride or the groom were required to reside in their chosen parish for at least fifteen days prior to the application for the license, either in town or in the country. This £2 license was obtained at either the Faculty Office, the Vicar-General’s Office, the Doctor’s Commons, or at the chosen church where the bride and groom were to be married. On top of these fees,the officiating clergyman needed to be paid (usually according to the position and means of the groom), and the clerk who legalized the marriage required a tip. Interestingly, in Britain, all fees relating to marriage were paid by the groom, and most of the marriage details were left on his shoulders, including the purchase of the bride’s wedding ring and her bouquet, as well as the bouquets and trinkets for the bridesmaids!

A marriage by license was a bit quicker, as either the bride or the groom were required to reside in their chosen parish for at least fifteen days prior to the application for the license, either in town or in the country. This £2 license was obtained at either the Faculty Office, the Vicar-General’s Office, the Doctor’s Commons, or at the chosen church where the bride and groom were to be married. On top of these fees,the officiating clergyman needed to be paid (usually according to the position and means of the groom), and the clerk who legalized the marriage required a tip. Interestingly, in Britain, all fees relating to marriage were paid by the groom, and most of the marriage details were left on his shoulders, including the purchase of the bride’s wedding ring and her bouquet, as well as the bouquets and trinkets for the bridesmaids!

In America, the arrangements and the details, if not the financial expense, of the wedding were largely assumed by the bride and her family, leaving the groom with little to do besides show up on the chosen date. The expenses of an American wedding could be heavy: for a church wedding, the services of the clergyman were requested and the church engaged for the date and hour appointed for the wedding. The sexton of the church was enlisted to have the church aired and comfortable for the impending nuptials. To him went the responsibility of making certain an awning and carpet were laid on the church floor, that a man was outside to assist guests from their carriages and maintain order, that another man was at the door to check invitations, and that a policeman was there to keep those uninvited away. To the sexton did much of the planning and preparation of a society wedding fall! Because of the superstitions held by America’s early settlers, weddings were frequently held in June, September, October, and January, though April was a popular month for city brides.

Roman Catholics prohibited marrying on Lent, and though Protestant marriages could be solemnized at any time, the old adage “Marry in Lent, you’ll live to repent” held fast, and that holiday was generally avoided. A nursery rhyme also influenced the day of the week on which a wedding was held–Monday for Wealth, Tuesday for health, Wednesday, best day of all; Thursday for losses, Friday for crosses, Saturday, no luck at all–though Friday was avoided as bearing the mark of Cain and also the stigma of Jesus’s crucifixion. The fashionable hour was high noon, though in imitation of the English, afternoon weddings were popular, and 3 pm was popular for winter weddings, and 4 pm in the spring. At one point in time, evening weddings were much in vogue, but fashionable society gave them up quickly.

Roman Catholics prohibited marrying on Lent, and though Protestant marriages could be solemnized at any time, the old adage “Marry in Lent, you’ll live to repent” held fast, and that holiday was generally avoided. A nursery rhyme also influenced the day of the week on which a wedding was held–Monday for Wealth, Tuesday for health, Wednesday, best day of all; Thursday for losses, Friday for crosses, Saturday, no luck at all–though Friday was avoided as bearing the mark of Cain and also the stigma of Jesus’s crucifixion. The fashionable hour was high noon, though in imitation of the English, afternoon weddings were popular, and 3 pm was popular for winter weddings, and 4 pm in the spring. At one point in time, evening weddings were much in vogue, but fashionable society gave them up quickly.

The appointment of the wedding gifts were taken very seriously in the United States. The Gilded Age was truly gilded for a bride, with presents growing absurdly gorgeous, displacing the old Dutch custom of giving the young couple household items and a sum of money, and turning into a bold display of wealth and ostentatious generosity. Wedding gifts were displayed at the home of the bride two or three days before the wedding, and the bride and her mother hosted a tea as a way to thank those who sent presents–and also allow everyone to see the lavishness of the gifts sent to the bride. They were customarily placed on tables covered with white damask cloths, which were set around in an empty room to facilitate a tour of the gifts. This was in direct contrast to English custom, where wedding presents were sent to the bride’s residence immediately after the wedding and were supposed to be put in their rightful places and definitely not arranged for the purpose of display. The French did one even better, as the nearest of kin collected a sum of money which was sent to the bride’s mother, who spent it on the trousseau, or jewels or silver, or however the bride so chose.

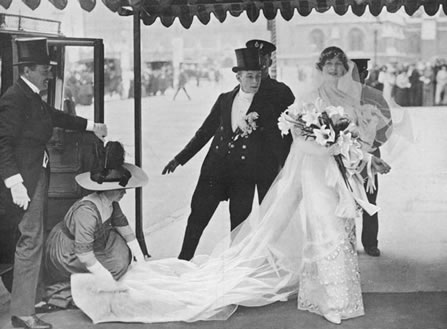

The most important parts of the wedding were the bride’s gown and trousseau. The traditional attire for a bride was a gown of soft, rich cream-white satin, trimmed simply or elaborately with lace, a wreath of orange-blossoms, and a veil of lace or tulle. The skirt had a train, and except at an evening wedding, waists cut open, or low at the neck, or with short or elbow sleeves (unless the arms were covered with long gloves) were not approved for brides. A wedding gown was supposed to be sumptuous and of the most costly materials, for the bride was privileged to wear her wedding down for six months after her marriage at functions requiring full dress. The train averaged eighty inches in length, though very tall brides wore ninety-five inch trains.

The most important parts of the wedding were the bride’s gown and trousseau. The traditional attire for a bride was a gown of soft, rich cream-white satin, trimmed simply or elaborately with lace, a wreath of orange-blossoms, and a veil of lace or tulle. The skirt had a train, and except at an evening wedding, waists cut open, or low at the neck, or with short or elbow sleeves (unless the arms were covered with long gloves) were not approved for brides. A wedding gown was supposed to be sumptuous and of the most costly materials, for the bride was privileged to wear her wedding down for six months after her marriage at functions requiring full dress. The train averaged eighty inches in length, though very tall brides wore ninety-five inch trains.

The richest wedding gown was worn, naturally, by Consuelo Vanderbilt on her wedding to the 9th Duke of Marlborough. Of rich white satin, covered with flounces of point d’Angelterre, the court train was fastened to her shoulders and attached to the skirt below the hips, falling in a straight line to lie three and a half yards on the ground. It was edged in its entire length with a borner of rose-leaves tied by true-lovers’ knots (the irony!), wrought with pearls and tiny silver spangles. Accordingly, Consuelo’s trousseau was suitably lavish and just as detailed in the press, with Vogue publishing an illustrated article and the New York Times running nearly two pages to describing her lingerie. In her memoirs, Consuelo details the agony of “[reading in] stupefaction that my garters had gold clasps studded with diamonds, and I wondered how I should live down such vulgarities.” For men wedding attire was much simpler: morning dress was de rigeuer, though an etiquette manual published in the late 1890s detailed the declining fashion for morning wear by American men, who increasingly appeared at weddings in tuxedos.

The actual service was an equally lavish affair: the bride was driven to the church with her father, where relatives and guests awaited. Once the bride alighted from the carriage, the bridesmaids and ushers preceded her, two by two, as her father escorted her down the aisle. As the bridesmaids and ushers reached the lowest altar step, they moved alternately left and right, leaving space for the bridal pair. When the bride reached the lowest step, the groom took her by her right hand and conducted her to the altar where they both kneeled on an elaborate kneeling cushion. Formerly, brides removed the whole glove for the groom to place the ring on her finger, but by the turn of the century, gloves were made with a removable left ring-finger, to facilitate easy access. After the ceremony, the bride and groom marched down the aisle to a choir and strewn rose petals and were immediately driven home. The English fashion for wedding-breakfasts–where prior to the wedding the bride, groom, and their families, sat down to a delicious champagne brunch to toast the impending wedding–did not take off in America, and instead, a reception held after the wedding was popular. Nonetheless, the bride and groom took leave of their families and guests, and in England, were conducted in a four-in-hand to their destination, and in the United States, to the train station.

The actual service was an equally lavish affair: the bride was driven to the church with her father, where relatives and guests awaited. Once the bride alighted from the carriage, the bridesmaids and ushers preceded her, two by two, as her father escorted her down the aisle. As the bridesmaids and ushers reached the lowest altar step, they moved alternately left and right, leaving space for the bridal pair. When the bride reached the lowest step, the groom took her by her right hand and conducted her to the altar where they both kneeled on an elaborate kneeling cushion. Formerly, brides removed the whole glove for the groom to place the ring on her finger, but by the turn of the century, gloves were made with a removable left ring-finger, to facilitate easy access. After the ceremony, the bride and groom marched down the aisle to a choir and strewn rose petals and were immediately driven home. The English fashion for wedding-breakfasts–where prior to the wedding the bride, groom, and their families, sat down to a delicious champagne brunch to toast the impending wedding–did not take off in America, and instead, a reception held after the wedding was popular. Nonetheless, the bride and groom took leave of their families and guests, and in England, were conducted in a four-in-hand to their destination, and in the United States, to the train station.

Widows marrying for a second (or third) time held noticeably simpler weddings. They were advised not to wear bridal veils, a wreath or orange blossoms, nor orange-blossoms on their gown, nor should they be attended by bridesmaids–though she could have pages should the wedding be a smart one. A widow could be given away by her father, uncle or brother, but it was optional after the first wedding, and many a quiet wedding did not feature the widow being “given away.” Formerly, widows married in gray or mauve, though it was later thought permissible for her to wear a cream or white dress, though some wore pale colors, with a matching hat or toque, and a bouquet comprised of mauve, pink, or violet flowers. Interestingly enough, the subject of a widow continuing to wear her first wedding ring was of importance, and etiquette advised the young widow to remove her first band, though she should not cease to wear it until she has arrived at the church. However, it was more usual for a formerly widowed bride to wear both rings for the remainder of her life.

The German custom of celebrating Silver weddings became a vogue in Britain of the late 1910s. The entertainments given to celebrate such an occasion were either an afternoon reception and a dinner party; a dinner party and an evening party; a dinner party and a dance; or a dinner party only, of some twenty or thirty covers. The invitations were issued on “At Home” cards three weeks beforehand, the cards being printed in silver with the name of the husband and wife, and the date and the time on them. Each person invited was expected to send a present in silver, and these were exhibited in the drawing room on the day of the Silver Wedding with a card attached to each bearing the name of the giver. At the afternoon reception, matters were much as at an afternoon wedding, with refreshments and a large wedding cake in which the wife made the first cut much as a bride would do. At the dinner party, the husband and wife went in first, followed by the guests according to precedence, and a wedding cake occupied a prominent place on the table. At the dance, the husband and wife danced the first dance together, and subsequently led the way into the supper room arm-in-arm, where their health was toasted. In the country, some Silver Weddings were celebrated in festivals ranging over three days, and balls, dinners, and treats were given to the neighbors, tenants, villagers and servants. At this celebration, the wife wore white and silver, or gray and silver.

Further Reading:

Manners and Rules of Good Society (1913) by A Member of the Aristocracy

The Book of Weddings (1907) by Mrs. Burton Kingsland

Manners and Social Usages (1897) by Mrs. John Sherwood

The Wedding Day in All Ages and Countries in Two Volumes (1869) by Edward J. Wood

Everyday Etiquette (1905) by Marion Harland and Virginia Van de Water

Thanks for the wonderful history on Edwardian weddings! I found it very interesting how variations of those traditions still continue today.

Well, I think it might be safe to say that our obsession with weddings hasn’t changed much since Edwardian times. 🙂 I don’t know if it’s still typical, but I remember going to a wedding when I was little where all the wedding gifts were arranged on tables with white table cloths and we all took a tour of them to see what the bride & groom got. I thought it was terribly boring.

Loved this thorough post. Thank you.

I love your site. I was wondering whether I could obtain your permission to copy a section of your article on weddings. The portion I am interested in, is the following:

“Of rich white satin, covered with flounces of point d’Angelterre, the court train was fastened to her shoulders and attached to the skirt below the hips, falling in a straight line to lie three and a half yards on the ground. It was edged in its entire length with a borner of rose-leaves tied by true-lovers’ knots (the irony!), wrought with pearls and tiny silver spangles.”

Proper acknowledgment shall be given in the appropriate sections of the book.

I remain in keen anticipation of your favorable reply.

Kind Regards,

Georgia

Hi Georgia,

Thank you so much for the compliment. I gladly give permission to excerpt from this website.

Regards,

Evangeline

such a helpful resource, thanks so much ; )