History has unfortunately immortalized Lady Duff-Gordon as the cold, imperious woman who, with her husband, Sir Cosmo, commandeered a lifeboat to themselves during the sinking of the Titanic, thus completely ignoring her position in history as one of the first couturiers.

History has unfortunately immortalized Lady Duff-Gordon as the cold, imperious woman who, with her husband, Sir Cosmo, commandeered a lifeboat to themselves during the sinking of the Titanic, thus completely ignoring her position in history as one of the first couturiers.

Lady Duff Gordon was born Lucy Christiana Sutherland in 1863. Her sister, the future romantic novelist Elinor Glyn, was born the following year. After a lackluster childhood in Canada and on the Isle of Jersey, Lucy made an even more lackluster match with the alcoholic James Wallace in 1884. In a move that presaged her innate audacity and independence, Lucy separated from and then divorced Wallace nine years later. She took her young daughter Esme, and after a stint at dressmaking from her home, Lucy opened the Maison Lucile in Old Burlington Street, in the heart of the West End shopping district. By the turn of the century, business at Maison Lucile boomed prompting a relocation in 1897 to 17 Hanover Square, and a further move (circa 1901-04) to 14 George Street. In 1903 the business was incorporated as “Lucile Ltd.” and in 1904, the couture house moved to its final premises at 23 Hanover Square. By that time, Lucy had remarried to Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon, a dashing sportsman whose keen business sense helped Lucy expand her business and social horizons even further.

Lady Duff Gordon was born Lucy Christiana Sutherland in 1863. Her sister, the future romantic novelist Elinor Glyn, was born the following year. After a lackluster childhood in Canada and on the Isle of Jersey, Lucy made an even more lackluster match with the alcoholic James Wallace in 1884. In a move that presaged her innate audacity and independence, Lucy separated from and then divorced Wallace nine years later. She took her young daughter Esme, and after a stint at dressmaking from her home, Lucy opened the Maison Lucile in Old Burlington Street, in the heart of the West End shopping district. By the turn of the century, business at Maison Lucile boomed prompting a relocation in 1897 to 17 Hanover Square, and a further move (circa 1901-04) to 14 George Street. In 1903 the business was incorporated as “Lucile Ltd.” and in 1904, the couture house moved to its final premises at 23 Hanover Square. By that time, Lucy had remarried to Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon, a dashing sportsman whose keen business sense helped Lucy expand her business and social horizons even further.

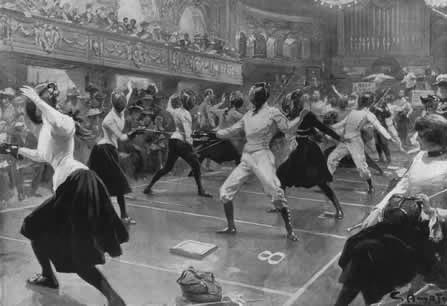

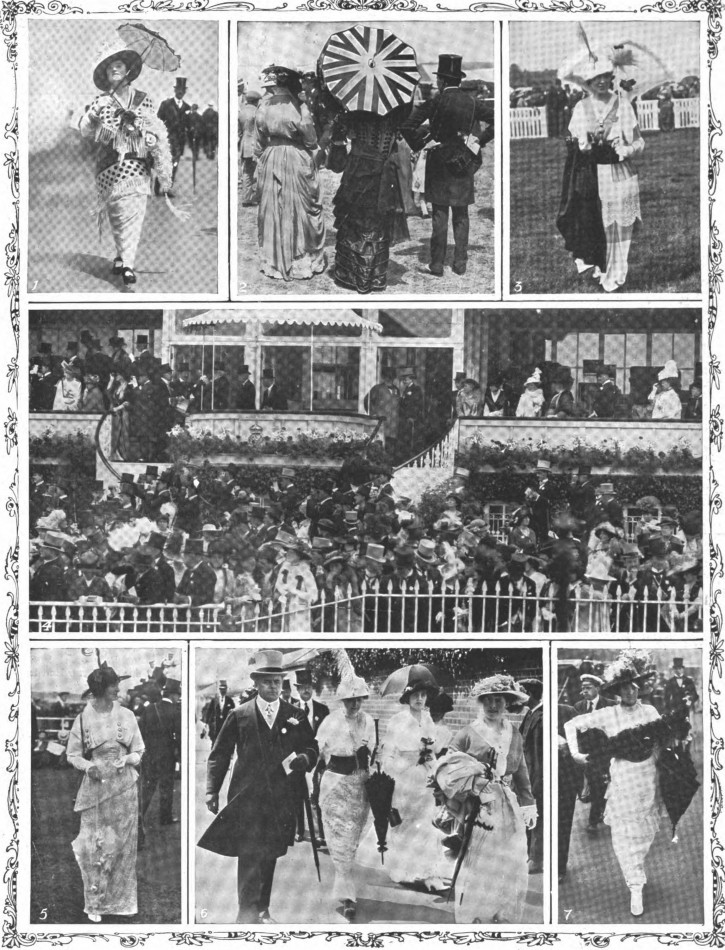

What made the Lucile brand unique was Lady Duff Gordon’s insistence upon individuality and innovation. Her designs were not startling and utterly different like those of Paul Poiret, but she honed in on what women craved in their attire: romantic, sensual gowns and lingerie full of the frou-frou, silks and lace so popular during the Edwardian era. Her most enduring and famous designs were for smash-hit operetta, The Merry Widow (1908). The large picture hat she designed for lead actress Lily Elsie, reminiscent of the “Gainsborough” hats of the 1780s, swept through fashionable society. Hats blossomed practically overnight in response, and remained that size until around 1912. Another innovation of the Lucile, Ltd was the fashion show, or mannequin parade. Ever since Charles Frederick Worth popularized actual showings of gowns on mannequins (models) in the 1850s, prospective clients liked to see gowns on the bodies of real women before choosing them. Lady Duff Gordon whipped this showing into a stage production, complete with stage, curtains, mood-setting lighting, music from a palm court orchestra, little gifts, and elegant programs. Clientele invited to the mannequin parade would relax with a cup of tea and a plate of biscuits (cookies) in chairs facing the “catwalk” as a vendeuse called out the names of what Lucy called her “emotional gowns,” which were influenced by literature, history, and her interest in the psychology and personality of her clients. The models were statuesque and beautiful, and soon became as famous and sought-after as Gaiety Girls.

What made the Lucile brand unique was Lady Duff Gordon’s insistence upon individuality and innovation. Her designs were not startling and utterly different like those of Paul Poiret, but she honed in on what women craved in their attire: romantic, sensual gowns and lingerie full of the frou-frou, silks and lace so popular during the Edwardian era. Her most enduring and famous designs were for smash-hit operetta, The Merry Widow (1908). The large picture hat she designed for lead actress Lily Elsie, reminiscent of the “Gainsborough” hats of the 1780s, swept through fashionable society. Hats blossomed practically overnight in response, and remained that size until around 1912. Another innovation of the Lucile, Ltd was the fashion show, or mannequin parade. Ever since Charles Frederick Worth popularized actual showings of gowns on mannequins (models) in the 1850s, prospective clients liked to see gowns on the bodies of real women before choosing them. Lady Duff Gordon whipped this showing into a stage production, complete with stage, curtains, mood-setting lighting, music from a palm court orchestra, little gifts, and elegant programs. Clientele invited to the mannequin parade would relax with a cup of tea and a plate of biscuits (cookies) in chairs facing the “catwalk” as a vendeuse called out the names of what Lucy called her “emotional gowns,” which were influenced by literature, history, and her interest in the psychology and personality of her clients. The models were statuesque and beautiful, and soon became as famous and sought-after as Gaiety Girls.

Lady Duff Gordon’s influence on the fashion industry didn’t end there. She opened branches of Lucile Ltd in New York (1910), Paris (1911), and Chicago (1915), and licensed her name to Sears, Roebuck & Co for a two-season lower-priced, mail-order fashion line. With such highs, it was inevitable that The House of Lucile would hit a snag. In 1917 she was embroiled in the lawsuit Wood v. Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon, wherein the judge stripped her of the use of her own name after she contracted the sole right to market her name to her advertising agent. Shortly thereafter, the House of Lucile began to collapse. Lucy’s connection with her fashion house was cut short after a restructuring, but as with Paul Poiret and many other trendy Edwardian fashion houses, the name Lucile and the inspiration of its namesake designer were considered old-fashioned and démodé. Lady Duff Gordon briefly resurrected her design career with a ready-to-wear collection, and remained influential as a fashion columnist, but her pre-war success proved elusive. After penning her florid and discreet memoirs Discretions and Indiscretions in 1932, Lady Duff Gordon died three years later at age 71.

Lady Duff Gordon’s influence on the fashion industry didn’t end there. She opened branches of Lucile Ltd in New York (1910), Paris (1911), and Chicago (1915), and licensed her name to Sears, Roebuck & Co for a two-season lower-priced, mail-order fashion line. With such highs, it was inevitable that The House of Lucile would hit a snag. In 1917 she was embroiled in the lawsuit Wood v. Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon, wherein the judge stripped her of the use of her own name after she contracted the sole right to market her name to her advertising agent. Shortly thereafter, the House of Lucile began to collapse. Lucy’s connection with her fashion house was cut short after a restructuring, but as with Paul Poiret and many other trendy Edwardian fashion houses, the name Lucile and the inspiration of its namesake designer were considered old-fashioned and démodé. Lady Duff Gordon briefly resurrected her design career with a ready-to-wear collection, and remained influential as a fashion columnist, but her pre-war success proved elusive. After penning her florid and discreet memoirs Discretions and Indiscretions in 1932, Lady Duff Gordon died three years later at age 71.

Despite living on as a Titanic “villan” and a footnote in legal history, Lucy Duff Gordon is a powerful and unforgettable woman in history. Through her imagination and eye for clothing, she helped lay the foundations for today’s couture and ready-to-wear industry, and the impact of fashion on society.

Further Reading

Lucile Ltd: London, Paris, New York and Chicago by Valerie Mendes and Amy de la Haye

The ‘IT’ Girls: Lucy, Lady Duff Gordon, the Couturiere “Lucile,” and Elinor Glyn, Romantic Novelist by Meredith Etherington-Smith and Jeremy Pilcher

Lady Duff Gordon, a website

Madame Lucile: A Life in Style by Randy Bryan Bingham

Lucile Couture at The Fashion Spot

Ur-Couture: The House of Lucile

Photos of Lucile’s clothing