To the Edwardians, everything had its place, and most importantly, everyone. For a society now transformed by the influx of wealth-sans-birth, a set rules were created to show who was in, and to keep others out. Prior to the Victorian era, Britain’s ruling class of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were composed of scarcely more than three or four hundred families, whose wealth and power stemmed virtually, with no exceptions, from land. By the end of the nineteenth century, these three or four hundred families had expanded tenfold and Society was alternately termed the “Upper Ten Thousand.” The main contributor to this drastic change were the increasing numbers of self-made millionaires and the declining values of land. The Reform Act of 1832, which abolished “rotten boroughs” and enabled the middle-classes and nouveaux riche the opportunity to rise in status as an MP, further contributed to the expansion of society. Thus, the newly elected MP and his family, energetically climbing the social ladder, needed guidance for behavior.

After the ascension of Queen Victoria, “gentility” was the accepted norm for social behavior not only for the middle-classes, but also the upper-classes. Outside of a few rebels (either left over from the wild Regency era, like Lady Blessington, or foreigners, like Louisa von Alten, 7th Duchess of Manchester), the first two or three decades of the Victorian era cultivated propriety and exclusiveness. To contain society against the social climbers, the card-and-call system was created. This system provided assurance that if your domestic and sexual reputation were unassailable, and your income above a certain level, you were permitted entry into a group of acquaintances with whom you could mix freely without feelings of social unease or constraint.

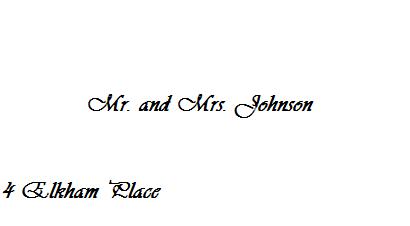

According to Lady Colin Campbell, you could not “invite people to your home, however often you may have met them elsewhere, until you have first called upon them in a formal manner and they have returned the visit.” The first step in the call-and-card system was to obtain calling cards. Previous generations brandished important-looking, ostentatious cards of very stiff, very highly-glazed vellum, with their names written in a series of flourishes. By the 1890s, cards had grown plainer, the gentleman’s name smaller than the lady’s, with name and address printed in an ordinary style. Married couples often had their names together on one card:

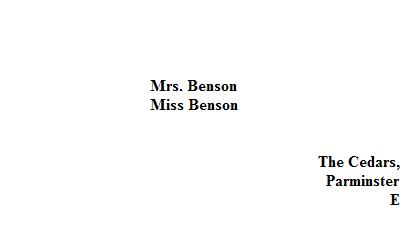

While unmarried daughters had their names place beneath that of their mother’s:

The method of calls varied, depending upon the occasion, but the typical call—the “calls general”—entailed the leaving of cards in the home of a prospective acquaintance. After an introduction was been made through a mutual friend, a formal visit was expected to be returned within three or four days. After receiving any particular hospitality such as a dinner or ball, it was necessary to call, or merely to leave cards at the door, within the few following days. The hours for calling were strictly confined between three and six o’clock p.m. For an acquaintance to call before luncheon would be the grossest presumption.

In regard to the calling cards, a lady left her own and two of her husband’s, one intended for the gentleman of the house and the other for the lady (meaning, the lady of the house would be given cards from both the caller and the caller’s husband). When leaving her husband’s cards, they would be placed on the hall table, and should the lady of the house be absent when one called, one corner of the card was to be turned down, which signified that one has called personally. The formal “morning” call was the follow-up to the card. Together, they indicated that a state of friendship existed between the two parties concerned, ready to be built upon as might seem convenient or pleasurable. However, if a call was followed by a card, it was a snub and obviously indicated that the lady had reached too high above her.

If a lady progressed past the stage of leaving cards and was invited to an “At Home,” the pressure had increased. Not only was she on display for the hostess, but most likely, the hostess’s own social circle, which meant she had to please and impress everyone. Furthermore, she had only fifteen minutes in which to do it. When she arrived at the house, she gave her card to her footman, who then handed it in at the door. If the mistress was willing to receive guests, the lady would enter the house and be led to the drawing room, where she would be introduced and promptly seated in the nearest vacant chair to her hostess. The question uppermost in the minds of the hostess and her friends was whether the newcomer make people feel awkward. Things that could create awkwardness included a lack of required family background, a lack of wealth (though a good background made up for poverty), a lack of assurance, lack of an acceptable moral reputation, and most important, the lack of ability to conform to the group’s social demands.

To be truly accepted into the new circle, the lady had to prove that she lacked nothing in all five respects; to fail one prerequisite would mark oneself as a red-flag that the quiet drawing-room could suddenly fall into chaos. However, since her very presence indicated a modicum of acceptance, there as another hurdle to leap over: was her voice pleasant; how did she speak (did she say “father,” rather than the correct “my father”); did she gush; did she wear the right clothing for the occasion; did she flutter and keep gestures to a minimum; and above all, did she carry herself with a poise the proclaims her a potential member of the circle as of right?

If the lady impressed the hostess and her friends, further calls were made and returned, and soon, the hostess’s card became a familiar sight in the lady’s card-basket as she was slowly absorbed into the circle. The hostess’s friends also initiated card-and-call moves of their own. The one invitation to tea was followed by another. Perhaps an invitation to a ball. A visit in an opera box. Then—triumph—there was an invitation to a dinner party!

Further Reading:

The Model Wife: 19th Century Style by Rona Randall

The Social Calendar by Anna Sproule

Etiquette of Good Society by Lady Colin Campbell

This is so interesting.

Delightful, many thanks.

So nice to read. It just struck me that the Museum of Bags and Purses in Amsterdam currently is exhibiting (until 30-1-11) accessories that ladies used to carry with them in the 19th century, including calling card cases, but the background information you provide, on the whole culture concerned is so intriguing! Thank you.

And many of these people called themselves Christians!