The administration of President Donald J. Trump has recently declared its intention to hide a 2014 report describing the CIA’s harsh detention and interrogation programs. By returning the document to Congress, this shields the report from ever being accessible to the American public through the Freedom of Information Act. Throwing this 6700-page report down the memory hole has more of a precedent than we would like to think. We’ve forgotten before.

The Water Cure

In 1902, almost seventy years before Vietnam and one hundred years before Iraq, there was a national conversation about how America should exercise its authority abroad, including how we should treat prisoners of war. It all began in America’s first overseas colony, the Philippines. At the conclusion of the Spanish-American War, the US purchased these islands from Spain for twenty million dollars, but America would spend twenty times that fighting the Filipinos, who did not want to simply exchange one colonial power for another. Occupation is ugly. The Senate Committee on the Philippines launched a detailed investigation into actions that “covered with a foul blot the flag which we all love and honor.” What were these actions?

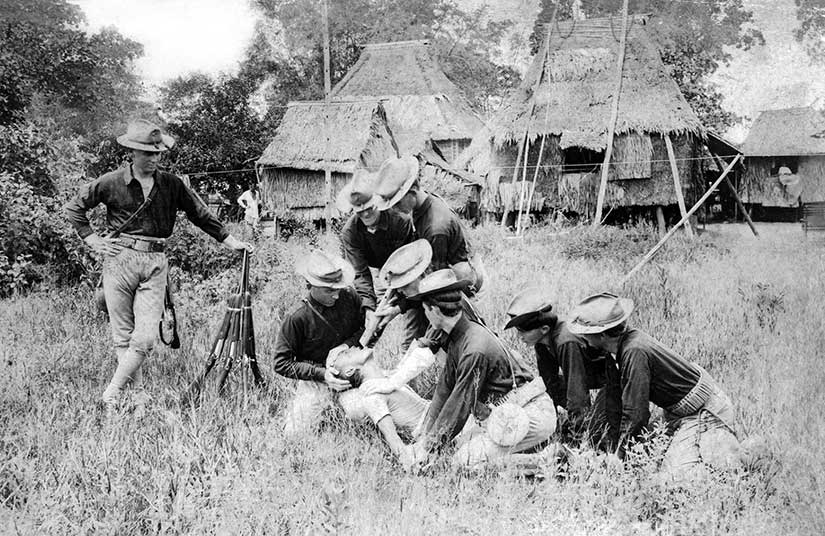

It was called the “water cure.” Soldiers laid a prisoner on his back, stood a man on each hand and foot, and forced a hollow tube into the victim’s throat. Through the tube they poured an entire pail of saltwater, dished up with a little sand to inflict a more severe punishment. When the prisoner did not give up, they poured in another pailful. Once the unlucky victim’s belly was “distended to the point of bursting,” a soldier would “tap” it with the butt of his gun. If the water did not spout high enough, they would jump up and down on his stomach. In the words of A. F. Miller of the 32nd Volunteer Infantry Regiment: “They swell[ed] up like toads. I’ll tell you it [was] a terrible torture.”

The Ends against the Means

Americans had not come to the Philippines to teach its soldiers enhanced interrogation techniques. Far from it. Americans claimed to have seized the islands to bring “the blessings of good and stable government,” in the words of President William McKinley:

…we come not as invaders or conquerors, but as friends, to protect the natives in their homes, in their employments, and in their personal and religious rights….[The American military must] win the confidence, respect and affection of the inhabitants of the Philippines…by proving to them that the mission of the United States is one of benevolent assimilation, substituting the mild sway of justice and right for arbitrary rule.

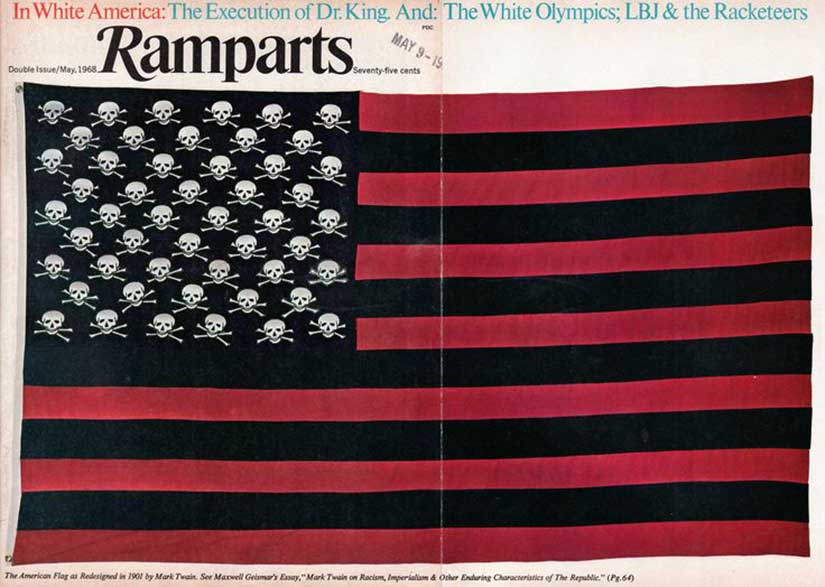

Novelist and prominent anti-imperialist Mark Twain pointed out the hypocrisy of Americans fighting a war to “civilize” another country and then succumbing to the very barbarism they sought to expunge. His essay “To the Person Sitting in Darkness” is one of his best and most biting pieces of satire:

The Person Sitting in Darkness is almost sure to say: “There is something curious about this — curious and unaccountable. There must be two Americas: one that sets the captive free, and one that takes a once-captive’s new freedom away from him, and picks a quarrel with him with nothing to found it on; then kills him to get his land.” …And as for a flag for the Philippine Province, it is easily managed. We can have a special one — our States do it: we can have just our usual flag, with the white stripes painted black and the stars replaced by the skull and cross-bones.

The End of a Conversation

The Senate hearings and national conversation did not come to any hard conclusions about what had happened in the Philippines, and who—if anyone—was to blame. (The Supreme Court did determine that Filipinos did not have all the legal rights of Americans because the Constitution did not quite follow the flag.)

Controversy was quelled by a conveniently timed declaration of “peace” in the Philippine islands on July 4, 1902. (It was not peace, though: fighting would continue until 1913, including other, bigger atrocities, like the hundreds of civilian dead at Bud Dajo.) But the American public was thrilled that the US military handed power over to a civil government under Governor William Howard Taft. Americans at home believed their problems were solved. However, because America did not finish the conversation, the public was forced to have it all over again in 1969 (when the My Lai massacre story broke) and in 2004 (when the Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse scandal broke). Now, with the threat to hide the 2014 torture report, we should be asking these questions all over again.

- Does the end justify the means?

- Do the means even work? (Does torture provide actionable information?)

- What happens when the use of torture is exposed, giving ammunition to our enemies and undermining the end goal of peace?

Unfortunately, Americans may be tiring of these questions before they can come to a consensus about the answers.

Read more about the history and use of the water cure in the Philippines and related issues at my author website.