The wealthy and well-born have always had their Grand Tours and foreign processions, but the Age of Steam and Electricity, if not the explosion of colossal wealth born from these two elements, made traveling for leisure a class-wide pastime. Thomas Cook opened travel to middle-class Britons, and Baedeker’s guide-books brought sophistication. However, it was the ties between the major cities of the United States and the courts of Europe (I hypothesize that the siege laid by the American heiress on European nobles created these links), and between the British Empire, which created a Society on a scale never seen before. By the end of the Edwardian era in 1914, it was common for Americans, Britons, and Europeans to live in a continuous state of Social Seasons! And all of this was facilitated by the ocean steamship.

The wealthy and well-born have always had their Grand Tours and foreign processions, but the Age of Steam and Electricity, if not the explosion of colossal wealth born from these two elements, made traveling for leisure a class-wide pastime. Thomas Cook opened travel to middle-class Britons, and Baedeker’s guide-books brought sophistication. However, it was the ties between the major cities of the United States and the courts of Europe (I hypothesize that the siege laid by the American heiress on European nobles created these links), and between the British Empire, which created a Society on a scale never seen before. By the end of the Edwardian era in 1914, it was common for Americans, Britons, and Europeans to live in a continuous state of Social Seasons! And all of this was facilitated by the ocean steamship.

The roots of the steamship reaches back to the 16th century, when there arose a growing need for a power other than the “fickle wind” or “laboring oar.” However, this demand did not reach fruition until the early 19th century, when shipping magnates grabbed any steam-powered invention in search of one which would push them and their ships ahead of the competition. Success came about in the 1820s, when the first steamers plied their trade between Dublin and Holyhead, and Dover and Calais.

The first vessel to cross the Atlantic was the Savannah, a ship which crossed old and new technologies, being fitted with a steam-engine and paddle-wheels, but also sails. It left New York on March 29, 1819 and arrived in Savannah, Georgia April 8th. The ship then left the Georgia port May 20th–with no passengers, as people probably feared the journey–for Liverpool, which it reached June 30th, a sailing time of 29 days and 11 hours. Needless to say, this successful trip sparked the beginning of the transatlantic trip, as well as travel to England’s far-flung colonies by steam.

The 1890s saw the construction of “Ocean Greyhounds,” which pulled the focus towards luxury and comfort on the high seas, as well as speed. Now steamships were equipped with staterooms, lounge areas, amenities such as pools and libraries and gyms,and costly decor. For the top ocean liner companies, such as Cunard, White Star, Hamburg-Amerika, and so on, competed for transatlantic travel (as well as steerage passengers headed from Europe for America) and the Blue Ribbon–a prize awarded to the fastest steamship across the Atlantic. By the 1910s, the average duration of a crossing was 6-9 days.

With so much passenger traffic from New York to Liverpool, Southampton to Cape Town, Le Havre to Genoa, Marseilles to Bombay, Singapore to Sydney, Tokyo to San Francisco, and all the way back again, order was definitely needed, and a number of guide books written specifically for ocean travel flooded the book market. Cook’s guides were old standbys, as were Bradshaw’s Routes, but a number of individuals produced charming and thoroughly-written books concerning traveling aboard a steamship , and what to do upon reaching one’s destination.

The best season for traveling across the Atlantic towards Europe was between April and November, which were, naturally, the months during which the social seasons were at their height. Though neither passports nor visas were necessary during this era, a passport was required for travel in Russia (and one was liable to be turned away if Jewish), and it was customary for lodgers in Prussia to submit their identification papers and their object for residing in Berlin, however temporary. Otherwise, travelers had to worry only about their luggage, their through-tickets, and customs when arriving in Europe.

The top steamship lines, all of which were fully equipped with luxurious first and second class accommodations. elegant restaurants and dining areas, and a number of amenities such as swimming pools and gymnasiums, were Cunard, White Star, Hamburg-America, North German Lloyd, and the Holland-America line. Lesser, but equally comfortable lines were American, Leyland, and Red Star. For first class travelers sailing from New York, suites and cabins on the top steamship lines could range from $75-300 (about $1800-7100 in 2010), while the same accommodations on the second tier of steamships could run between $40-125 (~$950-3000 in 2010). Lower fares would of course be found during the off-seasons: westbound between November 1st and April 30th; eastbound between October 1st and March 31st.

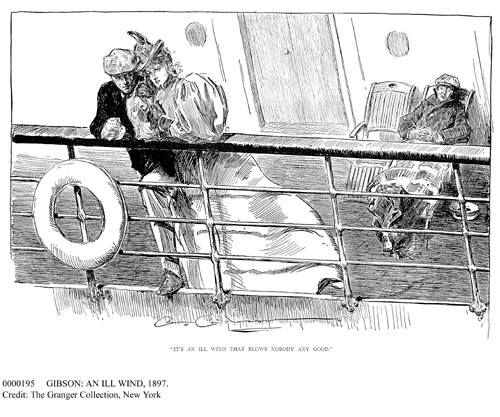

Once the steamship was chosen, and the berths paid for, passengers were advised to visit their ship the day before sailing, unless one was familiar with the line. This made travel much easier, as one could inspect the rooms, and befriend one’s steward or stewardess before the crush of fellow passengers in order to secure a nice bath time and have your steamer-chair (cost: $1) placed in a choice area on the deck.

Sailing day was next, and the docks were full of well-wishers, newspaper reporters, steamship employees, and passengers. It could be a chaotic time, but those who took the time–and money–to ease their entry aboard sailed right ahead to their rooms. Inside there might possibly be telegrams waiting, or flowers and fruit baskets sent from friends–though to combat sea-sickness, passengers were advised to tell their friends not to send food aboard. The trunks marked “Not Wanted” were sent to the hold, and the unmarked luggage, save tags with the stateroom number, was promptly unpacked and put away by the steward(ess).

Clothing for steamship travel was supposed to be simple and sturdy, to keep one warm and to cause as little fuss as possible in case of accident. A list of essential attire for a woman included one tailor made suit, one pair of thick silk or woolen tights, four sets of combination undergarments, shirtwaists, a sweater, a woolen wrapper for going to the bath, a dressy bodice for dinner, a pair of shoes with rubber soles or heels, and three pairs of pajamas. A man required a black coat for dinner, with the necessary shirts for evening attire, an old suit, woolen underclothing, a generous supply of handkerchiefs and socks, several pairs of pajamas, a bathrobe and slippers, and the requisite ties and collars.

Life at sea could vary in enjoyment, depending on one’s temperament, experience at sea, and congenial passengers, though amusements could be limited. Most steamers carried an excellent library, from which books could be obtained by applying to the steward in charge. Many boasted of ample deck room, where all sorts of athletic games were devised, and shuffleboard and the ring-toss were popular amusements. Card playing was another pastime, with bridge-whist being favored–and passengers were advised to look out for card-sharps plying their trade. The ship’s concert was always a feature of on the last day of a transatlantic voyage, during which money was collected for different institutions, both American and foreign, erected for the benefit of sailors. On German ships the concert was replaced by the captain’s dinner, during which the first-class dining saloon was lavishly decorated and the menu top-notch.

The bane of shipboard life was sea-sickness. There being no cure of the ailment (and there still is not), passengers took precautions before the date of departure. A variety of cures were: cotton in the ears, a pinch of bicarbonate of soda, powdered charcoal after each meal, and sniffing ammonia each morning. Drinking plenty of hot water was another cure, as well as a diet of well-masticated beef for the first three days at sea. Remedies of a more reliable bent were exercise, careful eating, and drinking either Vichy or Arpenta water, or a mild purgative. Mothersill’s Seasick Remedy, a powder in gelatine capsules, was vouchsafed by Bishop Taylor-Smith, Chaplain General of the British forces, Lord Northcliffe, doctors, bankers, scientists, and all manner of influential people, and The Shredded Wheat Company advertised Triscuits as “the perfect Toast, the ‘traveler’s delight,’ a satisfying, sustaining food on land or on sea.” .

After six to nine days at sea, depending on the speed of the ship, the end of the journey was neigh. Perhaps new friends were made, or relationships broken by the forced proximity, perhaps one’s destination was anticipated or dreaded, or one spent the entire time in misery, laid up with seasickness or another unfortunate ailment. Whatever one’s experience aboard, the hassle of travel was far from over once the ship docked, with customs, luggage, and through tickets to take care worry over. Foreign countries had different customs procedures, with the English being very lenient (spirits, tobacco, silver plate, copyrighted books, and music being the only things asked for), to very strict (as in France, Russia, Egypt and Constantinople). Train tickets could be booked in advance, speeding up the process of customs, and if traveling to the Continent, one was advised to mark the itinerary of the trip quite clearly (though, Thomas Cook was trusted because of the company’s efficiency in arranging extended travel).

After six to nine days at sea, depending on the speed of the ship, the end of the journey was neigh. Perhaps new friends were made, or relationships broken by the forced proximity, perhaps one’s destination was anticipated or dreaded, or one spent the entire time in misery, laid up with seasickness or another unfortunate ailment. Whatever one’s experience aboard, the hassle of travel was far from over once the ship docked, with customs, luggage, and through tickets to take care worry over. Foreign countries had different customs procedures, with the English being very lenient (spirits, tobacco, silver plate, copyrighted books, and music being the only things asked for), to very strict (as in France, Russia, Egypt and Constantinople). Train tickets could be booked in advance, speeding up the process of customs, and if traveling to the Continent, one was advised to mark the itinerary of the trip quite clearly (though, Thomas Cook was trusted because of the company’s efficiency in arranging extended travel).

The popularity of motor tours created a need for automobile accommodations, and arrangements for taking a motorcar abroad (the packing [$30-75] and freight included), was between $200-300, all of which could be handled by American Express. England required no duties for automobiles entering their ports, but in France and Germany, the cost was $12. Once the duty was paid in France, a seal would be attached to a conspicuous part of the car; the machine was then said to be plombé. On leaving the country, the seal was removed by an official and the duty was refunded. This was expensive, but not as expensive as hiring a car overseas, which could be priced as high as $500 per day!

For many–particularly newly wealthy Americans barred from the nation’s most exclusive circles–the cost was worth it if one could rub elbows with royalty and aristocratic luminaries and thumb your nose at those who snubbed you back at home. Others found that it strengthened the bond between upper class societies, mirroring the familial ties between the royal families of Britain and Europe.

Ultimately, the lines could blur between nationalities, forming a social group based on wealth and class rather than country of origin, which then diluted the importance of one social circle or another. Transatlantic society was now broken up into sets dependent upon one’s interests and friends. So independent did this make Society, the ever important London season was in danger of losing its place in the annual social round!!

Nevertheless, the meeting of and socializing with others of a like mind and background solidified the significance of the well-born and well-placed. Moreover, this constant moving about sparked the rise of photojournalism and society columns, which fed the need of the less fortunate public to feast on the adventures, exploits, and activities of their “social betters” prior to the advent of Hollywood cinema stars (the first of which was Florence Lawrence, the Biograph Girl). At what price, we all know now, but at the time, in the words of Mrs. Hwfa Williams, “It Was Such Fun!”

Note: The was published in the Fall 2010 issue of GILDED

Further Reading:

The Sway of the Grand Saloon by John Malcolm Brinnin

The Fabulous Interiors of the Great Ocean Liners in Historic Photographs by William H. Jr. Miller

The Edwardian Superliners by J. Kent Layton

Floating Palaces by William H. Miller

I’m writing a book about an Edwardian steamship now, so this post was invaluable. Thank you so much for writing it!

Thanks so much for this post. I’m dying for some one to write a romance set on a transatlantic journey from either New York/London or vice versa. One where the ship doesn’t sink or crash to add tension. Or the hero/heroine isn’t in steerage. Hmm!

Hello Elizabeth,

There is a series of mysteries that take place on some of the famous transatlantic liners, written by Conrad Allen:

Murder on the… Caronia; Celtic; Lusitania; Marmora; Mauretania; Minnesota; Oceanic; Salsette.

The books feature George Porter Dillman, American detective & Genevieve Masefield, English would-be socialite, in the early 1900’s.

While they are classed as mysteries, there is an element of romance involved. I felt the author was a bit stiff, but I read them for the descriptions of the travel and elegant atmosphere.

As usual, I would recommend starting with the earliest book, the Lusitania, as the main characters continue throughout the series.

Regards,

Sara

Sounds like a great setting for a novel.