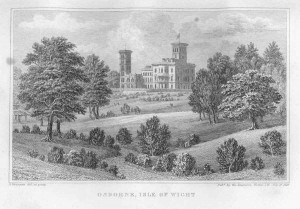

In the third week of December, Victoria traveled south aboard the royal train to Portsmouth where she boarded the 160-foot-long, 370-ton paddle-wheel steamer Alberta. The steamer bore the queen across the silent, gray waters of the Solent to the Isle of Wight, landing at East Cowes. Her Majesty then set off in a carriage through the small town, following York Avenue as it wound its way up the hillside, past the prosperous brick houses of her courtiers, and between a pair of granite piers adorned with bronze stags. The passage of her carriage down a gently curved drive flanked by the bare-leafed trees of winter sent a flagman scurrying up a twisting staircase to the top of a tall tower. He raised the royal standard. The Queen had arrived at the Italianate seaside palace, Osborne House.

In the third week of December, Victoria traveled south aboard the royal train to Portsmouth where she boarded the 160-foot-long, 370-ton paddle-wheel steamer Alberta. The steamer bore the queen across the silent, gray waters of the Solent to the Isle of Wight, landing at East Cowes. Her Majesty then set off in a carriage through the small town, following York Avenue as it wound its way up the hillside, past the prosperous brick houses of her courtiers, and between a pair of granite piers adorned with bronze stags. The passage of her carriage down a gently curved drive flanked by the bare-leafed trees of winter sent a flagman scurrying up a twisting staircase to the top of a tall tower. He raised the royal standard. The Queen had arrived at the Italianate seaside palace, Osborne House.

A creature of habit, and more so since Prince Albert’s death in 1861, Queen Victoria regularly returned to Osborne to celebrate the holiday. Her schedule rarely varied: she visited the mausoleum at Frogmore on the anniversary of Albert’s death and soon departed for Osborne, arriving a few days before Christmas, and remaining until the middle of February. Once there, the schedule included: afternoon drives in her pony cart despite inclement weather, with a brief stop at nearby Barton Man or, where members of the household, together with Victoria’s grandchildren, would gather to skate on the frozen-over lake. Unlike her other children who regularly joined her there for the holidays, the Prince of Wales preferred to celebrate with his own family at Sandringham, finding Osborne “utterly unattractive.”

or, where members of the household, together with Victoria’s grandchildren, would gather to skate on the frozen-over lake. Unlike her other children who regularly joined her there for the holidays, the Prince of Wales preferred to celebrate with his own family at Sandringham, finding Osborne “utterly unattractive.”

Christmas at Osborne was celebrated with all the festive touches of previous royal holidays at Windsor, though the widowed Victoria always regarded the celebrations somewhat wistfully. Footmen and housemaids spent hours decorating the house: chimney-pieces were draped with boughs of holly, yew and ferns, woven with cloves and set with candles to provide a sparkle; garlands of evergreen, dotted with holly and ivy, framed doorways; and poinsettias glowed red against the pastel walls. The florist provided miniature topiaries adorned with shimmer ing ropes of imitation jewels to grace tables, and large, festive bouquets of flowers added scent and color.

ing ropes of imitation jewels to grace tables, and large, festive bouquets of flowers added scent and color.

The celebration called for a dozen trees. Albert popularized the German custom of erecting a Christmas tree, but it was actually introduced to England by Queen Charlotte (consort of George III). The largest tree was placed in a tub at the foot of the grand staircase; others went into the drawing room, Princess Beatrice’s suite, and rooms for the royal household. The household tree was erected in the Durbar Room, and several smaller trees stood on tables covered in white cloth. All were carefully decorated by servants, their branches hung with blown glass and tin ornaments, bundles of cloves and cinnamon sticks, toffees and other small candies, silver tinsel, and red bows. Hundreds of candles, their holders clipped to branches, provided illumination, but the trees were not lit until Christmas Eve.

The afternoon of Christmas Eve found the queen making her appearance at the staff party in the servants’ hall. Members of the domestic staff, employees on the estate, and their wives and children, crowded the room to await her arrival. Tables were filled with pastries, cookies, tea and ale, and presents for the servants (always practical: clothing, bolts of cloth, meat pies, game, joints of meat, shoulders of lamb and crocks containing plum pudding). A footman handed each package to the queen, who took a particular delight in handing out gifts of toys, clothing or books, along with their very own gingerbread man, to the children. Carols were sung, followed by the national anthem, before the queen retired.

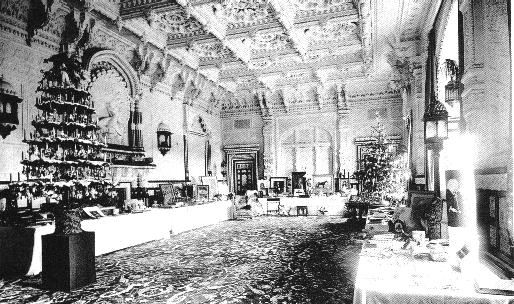

After tea, the queen distributed presents to the royal household in the Durbar room, where long tables draped in white cloth, fairly sagged beneath the weight of presents and the miniature trees crafted by the confectionery chef. These presents were of course much more lavish than those given to the domestic staff: gold or si lver cigarette cases, dressing gowns, jeweled cuff-links and watches for the men; and dresses, furs, and jewelry for the women. There were also an assortment of expensive, though useful household items, including silver salvers, tea services, silver coffeepots, paintings and books, along with signed photographs of members of the royal family encased in gilded or leather presentation frames. The queen and her family then exchanged gifts–usually paintings, vases, busts, expensive toilette and dressing services, and jewelry–which were then displayed on the tables in the Durbar Room. Each relative had his or her own table, and all of the gifts would be artistically arranged on top to give Queen Victoria the opportunity to be wheeled up and down the room to inspect them.

lver cigarette cases, dressing gowns, jeweled cuff-links and watches for the men; and dresses, furs, and jewelry for the women. There were also an assortment of expensive, though useful household items, including silver salvers, tea services, silver coffeepots, paintings and books, along with signed photographs of members of the royal family encased in gilded or leather presentation frames. The queen and her family then exchanged gifts–usually paintings, vases, busts, expensive toilette and dressing services, and jewelry–which were then displayed on the tables in the Durbar Room. Each relative had his or her own table, and all of the gifts would be artistically arranged on top to give Queen Victoria the opportunity to be wheeled up and down the room to inspect them.

And finally, Christmas morning. It began with a religious service, followed by luncheon at one, and tea at five o’clock in the queen’s sitting room. The traditional Christmas meal was a late dinner that began at nine. The pink and crimson dining room glowed in the light of the candles set within garlands of evergreens and holly, while bright red poinsettias and tendrils of ivy adorned the white damask tablecloth. To meet the holiday’s culinary needs, a month before the festivities, the chef de cuisine ordered up to 50 turkeys, a 140-pound baron of beef that took ten hours to roast over a spit, hundreds of pounds of lamb, dozens of geese, and crate after crate of vegetables, all shipped by train from Windsor. The confectionery chef and his staff spent days crafting 82 pounds of raisins, 60 pounds of orange and lemon peel, 2 pounds of cinnamon, 330 pounds of sugar, 24 bottles of brandy, and cup after cup of sugar into the Christmas mincemeat. This feast was followed by Christmas entertainment: a specially invited musician or singer who performed for the queen and her family before midnight brought the holiday to an end.

Finding comfort in Osborne, as she did with Balmoral, both monuments of her love and marriage to Prince Albert. to the end of her life, she regarded Osborne as “a clear paradise, which I deeply grieve to leave.”

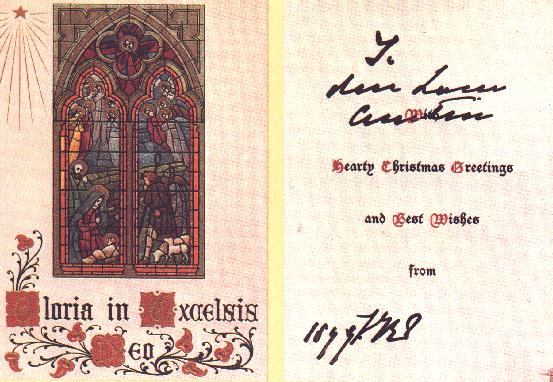

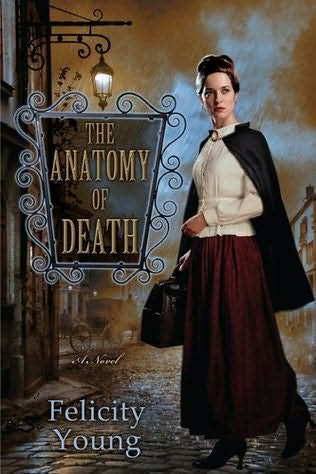

Christmas card from the Queen, 1897

Further Reading:

Twilight of Splendor: The Court of Queen Victoria During Her Diamond Jubilee Year by Greg King

I have a Xmas card [unsigned] but marked the royal household. The card cover is the grand staircase at buckingham palace at the 1848 state ball—the roundwood press.

Can you tell me what year this card represents?

Thank you Pat

Thanks for your thoughts on Queen Victoria at Christmas. Feel free to check out my article on Queen Victoria and her personal physician Sir James Simpson http://bit.ly/dYVQfH

Thank you for stopping by Ed! I enjoyed your article very much.