Of equal importance with the women’s suffrage movement was the extension of the franchise. Not surprisingly, until the dawn of the twentieth century, most men were ineligible to vote in Britain’s general and bye-elections, and of those who could vote but were of little power, their votes were frequently directed towards candidates backed by peers or other influential men. The Reform Acts of 1832 and 1867 were not enough; ridding the land of “rotten boroughs” or permitting male landowners or householders to vote still left a very large percentage of English men absent from the voting polls. Couple this with the fight for secret ballots in the 1870s and plural voting (not actually abolished until 1948), and the typical General or By-election of the Edwardian era was a circus.

The history of the franchise reform bills in England during the 19th century represented the struggle for democracy in the country. Because the class system was so entrenched in society, most–especially politicians–believed that only certain classes had the right to vote, and the fight for enfranchisement was a bitter one until the Representation of the People Act 1918. Until then, the Corrupt and Illegal Practices Prevention Act (1883), the Third Reform Act (1884), and an Act of 1885, held many suffragists at bay. The first act criminalized bribing and intimidation of voters and standardized the amount of money a politician could spend on their campaign, the second extended the same voting qualifications as existed in the towns to the countryside, and the third redistributed parliamentary seats and made every constituency of uniform importance. The voting population was now at 5.5 million, though 40% of males remained disenfranchised and only a fraction of the other 60% actually could vote, due to existing property legislation. These reforms were put to the test in the General Election of 1885, where the Liberals won a slim majority, but the agitation for Home Rule split the party, which led to another General Election in 1886.

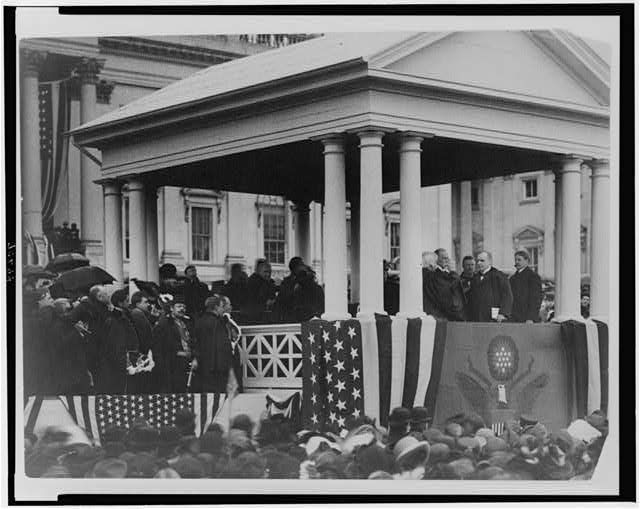

World War One put an end to the restrictions on voting (with the exception of women younger than 30) when politicians pushed through the Representation of the People Act 1918 when they realized it was unconscionable to deny the right to vote to the millions of men who fought for the country:

1. All adult males gain the vote, as long as they are over 21 years old and are resident householders

2. Women over 30 years old receive the vote but they have to be either a member or married to a member of the Local Government Register

3. Some seats redistributed to industrial towns

4. Elections to be held on a decided day each year

This Act tripled the number of eligible voters from 7.7 million in 1912 to 21.4 million by the end of 1918, and women now accounted for about 43% of the electorate. The Equal Suffrage Act was passed ten years later, by which women were given equal voting rights with men.