We’ve already run down a list of the basic sartorial necessities of a society woman in a previous post, where the author laments the “The Impossibility of Dressing on £1000 a Year“, but now we follow the Edwardian woman on her annual shopping trip to Paris. Most titled women reserved trips to Paris as a special treat–and most English ladies, including Queen Alexandra, made do with court dressmakers or the skilled needles of their discreet lady’s maid. However, the wealthiest Englishwomen (including Americans) and European women descended upon the Rue de la Paix to replenish their wardrobes in the chicest shops each season.

Were one to lay out a “shopping map” of Paris, one would find that, with certain exceptions, the dressmakers and jewellers are assembled in the Rue de la Paix, the milliners are in the Faubourg Saint-Honoré, the antiquity dealers in the Rue Lafayette, the Rue de Provence,—while the articles de Paris are on the Avenue de l’Opera and the Grands Boulevards.

Each quarter has its own magasin de nouveautés, such as the Louvre, the Bon Marché, the Trois Quartiers, the Printemps, where, not as much as at the London stores, but to an almost unlimited extent, everything can be bought.

Thus, as on the old market-places, to-day in the Rue de la Paix, the lady shopper who does not find what she wants at Doucet’s need seek only a few steps farther, at Worth’s, at Paquin’s, at Raudnitz’. If it be letter-paper, fancy picture-frames, porcelain ornaments, bronze statues, Parisian or cosmopolitan bric-a-brac she is looking for, she may wend her way up the Avenue de l’Opera and along the Boulevards, where she will see a bewildering display of novelties.

The centre of the old curiosity shops was originally the Hôtel des Ventes or Government auction-rooms in the Rue Drouot. Thence, little by little, the trade in antiques has radiated, reaching even across the river to the Rues de Seine, de Rennes, des Saints Peres, and the Quai Voltaire.

Behind the Palais Royal, in the Rues du Caire, du Mail, d’Aboukir, are collected the stores where feathers, artificial flowers, glass beads and passementerie trimmings are sold both retail and wholesale.

It is from localities such as these, which for generations have been monopolised by one especial branch of commerce, that Paris shipped to the United States over one million francs’ worth of gowns and lingerie during the first three months of 1905; 2,069,000 francs’ worth of hats and artificial flowers; 1,468,000 francs’ worth of fans, brushes, opera-glasses and other ornaments classed under the general head of articles de Paris.

These figures give some idea of the activity of trade carried on, and they make one realise, at the same time, the immense superiority of such jewellers as Boucheron and Cartier, such milliners as Taty and Reboux, such tailors as Francis and Linker,—who in the midst of so keen a rivalry hold a leading place.

As for leather goods, the palm is given to the English merchants who have established themselves in the Rue de la Paix. Leuchars and Kendall surpass, in the of their tiny shop windows, any perfection that the French have attained in the way of dressing-cases, portfolios, purses, bags, and so on.

The system of business in Paris shops differs somewhat from that of London. It will be found, too, that Paris shopkeepers are, as a rule, far more obliging and willing to be agreeable to their customers. Nearly all the large shops will send goods on approval (à condition), and nearly all will take back goods that have been paid for, when purchasers have changed their mind within a few days, and, what is more, they frequently refund the money. It is not even necessary to make an exchange. All that a customer has to do is to take back the article (with the receipted bill if possible) and say to one of the attendants in the department in which the article was purchased, “Je viens faire un rendu.” The shop-walker makes a note, writes down the name and address of the returner of the article, and the attendant accompanies his client to the caisse, where the money is refunded. When the articles returned consist of material or ribbon cut by metre from a piece the goods returned must measure at least 2 or 3 metres. This, of course, would not apply to very rich and rare lace, silks, or trimmings.

English people are often inclined to think that Paris dressmakers and modistes charge most expensive prices. But this is an exaggerated view. Wages are no higher in France than in England, and the incomes of the middle class are far lower, yet a glance at the women of all classes in the streets of Paris will show that the ethics of dress are far higher here than in London. This is due to many causes, but the principal reason is that where an Englishwoman would have two or three indifferently-built gowns, the Parisienne of the same class will have a single well-cut, well-made and silk-lined gown. Of this she will take great care, changing it as soon as she returns to her house and brushing and putting it away carefully. So that a person of even the most modest means can pay for a well-made gown. It is difficult, though not impossible, to buy a really well-cut, well-made woollen gown, lined with silk and simply trimmed, in Paris under 150 francs (£6), but from that price upwards charming gowns can be purchased from the smaller dressmakers. The larger shops, such as the Printemps, the Bon Marche, and the Louvre make charming gowns, not silk-lined, for even less than that sum, and give two or three fittings if necessary.

But every Parisienne employs her own petite couturiere, generally a beginner who has started her own modest establishment after some years’ apprenticeship in one of the larger and well-known establishments of the sartorial capital. Besides Paquin, Doucet, Callot Sours, Bechoff David, Worth, Drecoll and others of the same rank, who are the first couturiers in the world, there are smaller houses which create their own models and turn out delightful and original costumes as exquisite in every detail as those of the larger houses, from prices beginning at £12 for a silk-lined cloth gown. It is the same with modistes. The most elegant modistes of Paris charge £10 or £12 for a hat that might cost £6 or £8 at a lesser modiste’s, and far less at a third-rate house. It must be remembered that it is not the materials of

a costume or of a hat which make its value, but the novelty of the model. Once copied by the lesser houses a model loses all its value.

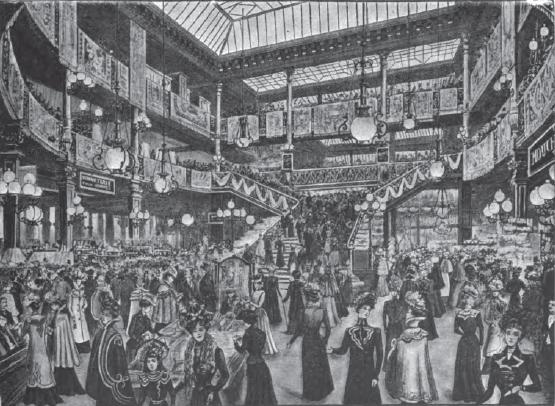

That Beraud painting is wonderful. Very evocative of the bustling 1907 era.

You know if I was selecting a PhD topic in history now, I would choose some sort of cultural or leisure time activity in Edwardian life that included women – pleasure piers, wintergardens, open air band stands, collections of fine and decorative arts created by individual families, the Garden City Movement, shops and tea rooms etc.

Thank you.

That would be a fascinating topic. I’d read that! 😀

I had read before that Queen Alexandra frequently shopped in Paris, particularly at Worths.