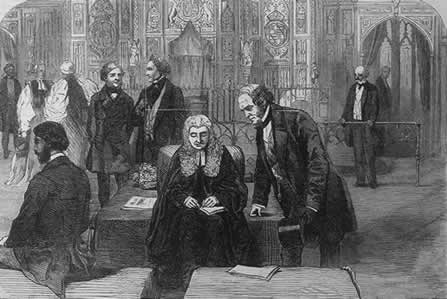

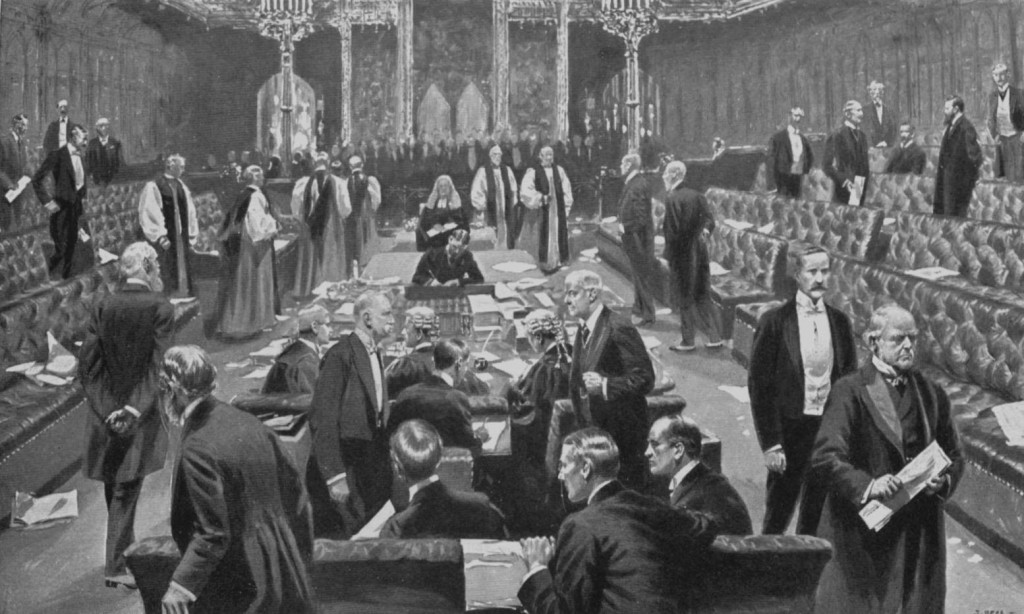

The House of Lords measured 100 feet by 50 feet, and was decorated in solemn hues of gold and crimson, with lofty stained-glass windows depicting the past kings and queens of England. At the end of the Chamber was a canopied throne of gold where the reigning monarch sat when opening Parliament. On the steps to the throne the eldest sons of peers and privy councilors were privileged to stand during the sittings of the House of Lords. Immediately before this was the Woolsack, a red ottoman upon which the Lord High Chancellor presided over the House. Unlike the Speaker of the House of Commons, the Lord High Chancellor could take part in debate. At his right sat the Lords Spiritual–the Archbishops and Bishops. To their right were the peers supporting the current Government with the Ministers seated in front of them. Opposite them sat the Opposition peers. In front of the Lord Chancellor was a table, upon which lay volumes of Parliamentary procedure and writing materials, where three clerks in wigs and gowns sat. Facing this was a desk for the reporters of Parliamentary debates, who relieved one another every fifteen minutes.

The House of Lords measured 100 feet by 50 feet, and was decorated in solemn hues of gold and crimson, with lofty stained-glass windows depicting the past kings and queens of England. At the end of the Chamber was a canopied throne of gold where the reigning monarch sat when opening Parliament. On the steps to the throne the eldest sons of peers and privy councilors were privileged to stand during the sittings of the House of Lords. Immediately before this was the Woolsack, a red ottoman upon which the Lord High Chancellor presided over the House. Unlike the Speaker of the House of Commons, the Lord High Chancellor could take part in debate. At his right sat the Lords Spiritual–the Archbishops and Bishops. To their right were the peers supporting the current Government with the Ministers seated in front of them. Opposite them sat the Opposition peers. In front of the Lord Chancellor was a table, upon which lay volumes of Parliamentary procedure and writing materials, where three clerks in wigs and gowns sat. Facing this was a desk for the reporters of Parliamentary debates, who relieved one another every fifteen minutes.

Near the strangers’ gallery were three or four benches in the center of the floor, facing the Lord Chancellor, known as “the cross benches,” upon which sat those Princes of the Blood Royal who had been created peers of the realm and who, though they were allowed to vote, belonged to no political party. A few peers also chose to be seated thus. Behind these benches was the place known as “the Bar,” where the Speaker and the members of the House of Commons stood when summoned by the Black Rod to the House of Lords to hear the Royal assent signified to the Bills agreed upon by both Houses. The divisions in the House of Lords mirrored that of the Commons, except the peers declared themselves in the Old Norman French “Content” or “Non Content” rather than “Aye” or “No,” and the tellers counted these votes with a white wand.

Near the strangers’ gallery were three or four benches in the center of the floor, facing the Lord Chancellor, known as “the cross benches,” upon which sat those Princes of the Blood Royal who had been created peers of the realm and who, though they were allowed to vote, belonged to no political party. A few peers also chose to be seated thus. Behind these benches was the place known as “the Bar,” where the Speaker and the members of the House of Commons stood when summoned by the Black Rod to the House of Lords to hear the Royal assent signified to the Bills agreed upon by both Houses. The divisions in the House of Lords mirrored that of the Commons, except the peers declared themselves in the Old Norman French “Content” or “Non Content” rather than “Aye” or “No,” and the tellers counted these votes with a white wand.

Also present in the House of Lords were the peeresses, whose galleries lined both sides of the Upper Chamber, foreign Ambassadors, invited guests (“Strangers”), and reporters, who each also possessed galleries of their own. But unlike the House of Commons, where the sexes were separated into their own galleries, ladies and gentlemen could sit together.

Also present in the House of Lords were the peeresses, whose galleries lined both sides of the Upper Chamber, foreign Ambassadors, invited guests (“Strangers”), and reporters, who each also possessed galleries of their own. But unlike the House of Commons, where the sexes were separated into their own galleries, ladies and gentlemen could sit together.

Contrary to popular belief, most peers sat regularly in the House of Lords, and throughout the nineteenth century, attendance reached its peak in the 1830s, 1850s, 1870s and late 1880s–no doubt spurred on by such issues like the Irish Question or the Deceased Wife’s Sister Act. However, sittings were usually brief, a quarter of an hour not infrequently the length of a sitting. Sometimes a sitting might have extended to an hour, on still rarer occasions it prolonged until seven pm, and at times on two nights of a Session of seven or eight months’ duration, the sitting could last until midnight. But it was more likely that newspaper reports would announce the adjournment of the House fifteen minutes after it first sat. Far from being lazy, the reasons behind these short sessions was because the House of Lords was practically barred from initiating legislature of an important nature.

Sittings in the House of Lords began at four, though as a rule, no business was done until half-past four, and during this interlude, the Lord Chancellor would essentially twirl his thumbs. The number of peers of the realm fluctuated over the years, but generally hovered around five hundred and seventy. Where the House of Commons required forty members to “make a House,” three peers formed a quorum, but if it appeared on a division that thirty lords were not in attendance, the question was declared not decided.

Sittings in the House of Lords began at four, though as a rule, no business was done until half-past four, and during this interlude, the Lord Chancellor would essentially twirl his thumbs. The number of peers of the realm fluctuated over the years, but generally hovered around five hundred and seventy. Where the House of Commons required forty members to “make a House,” three peers formed a quorum, but if it appeared on a division that thirty lords were not in attendance, the question was declared not decided.

When the Government changed, the parties crossed to floor, with the “ins” sitting on the benches to the right of the Lord Chancellor, and the “outs” occupying those on his left. The Lords Spiritual always occupied the same benches on the Government side of the House, near to the Throne, no matter which party was in office. Twenty-six in number–the Archbishops Canterbury and York, and twenty-four bishops–were distinguished from the Lords temporal by their full, flowing black gowns and their lawn sleeves. The peers in the House were much more soberly dressed except at the opening of Parliament by the Sovereign, whereupon they appeared in scarlet robes, slashed across the breast with stripes of ermine, few or numerous according to the low or high degree of the wearer in the peerage. Though the Lords temporal–royal peers, dukes, marquesses, earls, viscounts and barons–were allotted certain benches according to their rank, they only sat thus during the opening of Parliament.

Opinion of the day claimed that speeches made in the House of Lords were of an eloquent and more able quality than those made in the Commons, for members of the lower house spoke as often as possible to get their names in the papers. The demeanor was quite different in the Lords as well–none of the fury and raucous which characterized the doings in the Commons. But if order cannot be maintained, the procedure of the House provides for the quelling of the disturbance by the reading by the Clerk of two old Standing Orders in relation to asperity in speech and quarrels in the Chamber.

Opinion of the day claimed that speeches made in the House of Lords were of an eloquent and more able quality than those made in the Commons, for members of the lower house spoke as often as possible to get their names in the papers. The demeanor was quite different in the Lords as well–none of the fury and raucous which characterized the doings in the Commons. But if order cannot be maintained, the procedure of the House provides for the quelling of the disturbance by the reading by the Clerk of two old Standing Orders in relation to asperity in speech and quarrels in the Chamber.

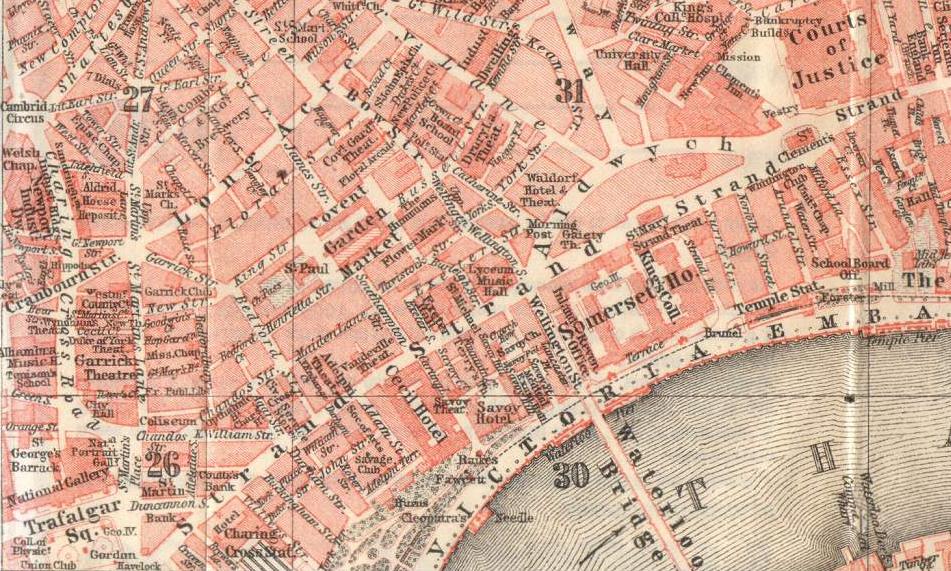

Though of lesser political power, the House of Lords was the Supreme Court of Appeal from the Courts of Justice of the United Kingdom. If a claimant felt an injustice was done him by the decision of any of the law courts, they could come to the House of Lords, whose judgment on the matter would be final and irrevocable. This court sat on Mondays, Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays throughout the legal year from 10:30 am to 4 pm, and gravity, dignity and decorum reigned supreme. No witnesses were examined, nor was there a jury, and sparring between opposing lawyers was unheard of. The lawyers would address the House at the Bar and lay down, in placid, conversational style, the facts of the case and the points of law on which he relied for judgment. After both sides presented their case, the House would adjourn and the parties involved would be informed of the day on which the House would deliver its decision.

As with such great power, there came resentment, and the growing dissent against the House of Lords affected the House of Commons, where the Conservative Party was defeated in 1906, and then invoked a Parliamentary crisis in 1910. Meanwhile, books and pamphlets filled bookstalls with such titles as Peers and bureaucrats: two problems of English Government and The Old Order Changeth, the Passing of Power from the House of Lords, one of which went so far as the proclaim that “our victory at Waterloo was a great misfortune to England….the feudal system, broken down and disorganized all over the Continent by Napoleon, preserved its old tradition in these islands…[and Britain] is now a hundred years behind the rest of Western Europe.”

As with such great power, there came resentment, and the growing dissent against the House of Lords affected the House of Commons, where the Conservative Party was defeated in 1906, and then invoked a Parliamentary crisis in 1910. Meanwhile, books and pamphlets filled bookstalls with such titles as Peers and bureaucrats: two problems of English Government and The Old Order Changeth, the Passing of Power from the House of Lords, one of which went so far as the proclaim that “our victory at Waterloo was a great misfortune to England….the feudal system, broken down and disorganized all over the Continent by Napoleon, preserved its old tradition in these islands…[and Britain] is now a hundred years behind the rest of Western Europe.”

The trouble began when in 1909 David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, introduced into the House of Commons the “People’s Budget”, which proposed a land tax targeting wealthy landowners, among other benefits for the common people of England. This bill was immediately defeated by the House of Lords, and in response, the Liberal Party made the curtailing of the House of Lords’ powers their primary campaign issue for the General Election of January 1910.

The chaos produced by this was enormous, and King Edward let it be known his willingness to raise men to the peerage to force the bill to pass through the House of Lords. He died in May however, before he could implement this, and when the Conservative Party, with their Liberal Unionist allies, gained more seats than the Liberals, the fight intensified. After another general election in December, the Asquith Government secured the passage of a bill to curtail the powers of the House of Lords. In the end, The Parliament Act 1911 effectively abolished the power of the House of Lords to reject legislation, or to amend in a way unacceptable to the House of Commons; most bills could be delayed for no more than three parliamentary sessions or two calendar years.

Further Reading:

Edwardian England: 1901-1914, ed. Simon Nowell-Smith

The Book of Parliament by Michael MacDonagh

How We are Governed: Guide for the Stranger to the Houses of Parliament by Howard Vincent

The House of Lords Question by Andrew Reid, Philip Stanhope, and Robert Collier Monkswell

The Rise of the Democracy by Joseph Clayton

House of Lords on Wapedia

Wow, what great information and pictures!

Great information! I’ve found most sources on this confusing as I do not

have a British background and don’t know much about how their government

functions.

Judith

My husband and I sat in the public gallery inside the House of Commons. It was exhilarating being right there where history has taken place. As a British royal historian, I had goosebumps. I can’t wait to return one day… maybe even get into the House of Lords! 😉

Thanks for such a wonderful site!

Regards,

Mandy