While watching Giles and Sue Live the Good Life, a hilarious, reality-TV take on a British sitcom, I was struck by the similarities between today, the 1970s, and the Edwardian period.

While watching Giles and Sue Live the Good Life, a hilarious, reality-TV take on a British sitcom, I was struck by the similarities between today, the 1970s, and the Edwardian period.

All three time periods came after long periods of extensive growth, consumerism, and amazing technological advances. However, though many people were much more prosperous than their forefathers, society was experiencing a bout of uncertainty and instability. To focus on the Edwardian era specifically (since that is the topic of this blog, natch), the lives of the professional and middle-classes were both comfortable and unsettled.

The boom years of the Victorian era opened up so many fields for men and women, and now that they’d worked, worked, worked to attain a prosperous life, the fashionably appointed home, fully-stocked larder, luxurious clothing, the servants, and extended holidays at the sea or even abroad appeared a bit overdone. Adding to the ennui was the hustle and bustle of city life, where a person found it difficult to relax with carriages and motorcars clattering down the streets, construction of new buildings filling the days and nights, and the people walking, riding, talking, cycling, playing, entertaining, etc, never let up.

The backlash against this was understandable, and the anxious middle-class took to the Arts and Crafts movement. This was an art, architecture, and lifestyle philosophy that grew out of the Pre-Raphaelites in the 1860s and attained recognition in the 1880s and 1890s.

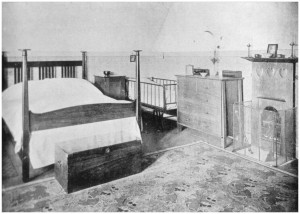

With its emphasis on clean lines, natural decoration, and organic design, as well as an “advocacy of economic and social reform”, this was essentially an anti-industrial movement desiring to move away from the arrogant, the fussy, and the self-satisfied.

The philosophy bore fruit mostly in architecture and interior design, but from it also sprang the Garden city movement initiated in 1899 by Sir Ebenezer Howard, who proposed suburban cities “planned, self-contained, communities surrounded by ‘greenbelts’ (parks), containing proportionate areas of residences, industry, and agriculture.”

Howard was inspired by Edward Bellamy’s utopian novel, Looking Backward, and wrote To-morrow: a Peaceful Path to Real Reform (reprinted in 1902 as Garden Cities of To-morrow), which offered “a vision of a town free of slums and enjoying the benefits of both town (such as opportunity, amusement and high wages) and country (such as beauty, fresh air and low rents).”

An ideal garden city would “would house 32,000 people on a site of 6000 acres (2400 ha), planned on a concentric pattern with open spaces, public parks and six radial boulevards, 120 ft (37 m) wide, extending from the centre. The garden city would be self-sufficient and when it had full population, another garden city would be developed nearby.”

He further “envisaged a cluster of several garden cities as satellites of a central city of 50,000 people, linked by road and rail.” Only two garden cities were created–Letchworth and Welwyn–and of the two, Letchworth, Hertfordshire, was the most famous.

A 1911 article in La Follette’s Weekly Magazine gushed over Letchworth:

A 1911 article in La Follette’s Weekly Magazine gushed over Letchworth:

Letchworth is a town made to order. You realize this the moment yon step off at the station after the rapid run of thirty-four miles from London. You see immediately that Letchworth is made of a single plan. Its factories are shut off in one corner of the city, at a spot adjoining the railroad, and in the direction opposite to that of the prevailing wind. The workingmen’s cottages, splendidly built and with a’ maximum of light and air, are within a few hundred yards of the factories, but are separated by a wide boundary of grass. The other houses are not cramped or huddled, nor are they built with a complete independence of one another, but are arranged in clusters and groups, with an infinite variety, but with an attempt at harmony. The shops, the batiks, the schools, the public buildings, the churches, the parks, the play-grounds, the open squares, all have suitable and defined locations. The roads, streets and avenues are laid out in advance, each being given a width adapted to its probable needs. The gas mains, wires, pipes and other underground connections, are put in before (and not after) the street is paved. The city is planned as a house is planned. Everything to the last detail is foreseen. It is intended to make as few changes as possible in the years to come.

Letchworth…is never to exceed a population of thirty-five thousand. Of the six square miles of Letchworth only two are to be built upon. These two square miles will very comfortably house thirty-five thousand people in detached dwellings, with gardens, and public play-grounds, parks and other open spaces. But this urban part of Letchworth is always to be surrounded by a belt of twenty-five hundred acres of land. For all time Letchworth is to have the country at its doors. It is to have the vivifying touch of the open land. It is to be saved from contact with the slums and evil tenements which would surely spring up around it, if it were to grow to the very limits of its land. In its turn the agricultural belt should prosper by the rise within its centre of a city with thirty-five thousand consumers. The farmer situated on the Letchworth belt can daily drive to town with eggs and milk and butter and vegetables and the proximity of the city will give a money value to the land, just as the proximity of the land will give a healthy value to the city.

Garden city residents were no doubt encouraged to take advantage of growing and raising their own vegetables and fruits and livestock, respectively, and with the passing of the Small Holdings Act of 1892, one could yield a satisfactory income from market gardening, bees, poultry, pigs, cut flowers, fruit culture, etc etc. Add to this the leisure time and entertaining, and sporting events (cricket, lawn tennis, bowls, golf, rugby, swimming, etc), and the garden city was the Edwardian’s vision of paradise. Of course the reality was not as shiny as Howard’s ideals, but the garden city movement–and the quest for a simple, organic life–has obviously never left us!

Do you “live green” (in 21st century speak)? Any experience gardening or raising livestock? Would you ever chuck it all to live in the country and grow your vegetables and fruit?

Further Reading:

Visit Letchworth’s official website

Letchworth: The First Garden City by Mervyn Miller US | UK

fascinating, these waves of change. i’ve been looking into the arts & crafts movement but hadn’t gotten as far as the garden cities. and we have, in fact, chucked it all to live in the country!

They really are. If I’m not being too nosy, what were your reasons for moving to the country?

There’s also a show called Edwardian Farm that I saw on Amazon.co.uk. I love Sue Perkins, I just watched the documentary she did on Anne Lister. I’ve also seen her on Graham Norton and she’s hilarious! As for The Good Life, which was one of my favorite sitcoms, I’m always amazed that they never tried to Americanize that one. I think it would be hilarious to see a couple try to grow vegetables on a miniscule terrace in New York or try to have a goat in their back yard.

I’ve been meaning to catch up with that series. The BBC also aired a miniseries set in 1890 Wales, following a modern-day family living as farmers in Snowdonia. And I love Sue Perkins–her droll, self-deprecating humor slays me. I share your surprise that The Good Life wasn’t Americanized–but then again, we had Green Acres in the 1960s, and it seems networks shied away from anything “rural” after that decade.

I don’t have experience gardening or anything like that, but it does sound idyllic!

reasons for moving to the country, hmm. more space inside and out for a lot less money, to be somewhere really beautiful, quiet, peaceful, and connected to our food. we found a place where there’s strong community, and the children are surrounded by other homeschoolers, lots going on together, so they meet friends at dance and again at forest school etc.. the chance to forage and grow more of our own food. we live close to an organic farm, it’s really important to me that our food is local and organic. the price for organic in london was astonishing! i’d like to keep chickens but haven’t been so courageous yet.. i’m an artist and a lot of my work involves traditional skills, so it is a great situation to learn. i can walk out my door and keep walking for so long without meeting a road, i haven’t been stopped by one yet! and at the same time we’re within an hour of london, so i can still get in to see friends, go to museums, take the children on field trips. it works for me! x

Your life sounds very peaceful and relaxing! Now I’m tempted to look into farms…