By the close of the Great War, death had become a constant companion for both military personnel and civilians alike, yet no one expected that long after the ceasing of hostilities, between 50 to 100 million people worldwide would be struck dead by a seemingly harmless strain of influenza. Yet, just as quickly as the Spanish Flu swept across the globe, it disappeared just as swiftly from both people’s memories and the annals of history. In fact, during much of the first wave and second wave of the flu (mid-to-late 1918), reports on the disease varied from confusion to indifference, and knowledge of how it spread (and from where), and how it could be treated or prevented were also muddled.

The Medical Critic and Guide, September 1918 —

According to Spanish and French publications the new disease called Spanish grippe, which appeared a few weeks ago in Madrid, has invaded Switzerland and is spreading rapidly. In Madrid alone there have been 100,000 cases and already nearly 1,000 persons have died. On July 9, there were said to be 6,800 cases in the Swiss Army. Although the grippal character of the disease has been recognized the causation is obscure. The absence of the influenza bacillus has been demonstrated. The onset of the disease is sudden with severe headache, high fever, throat irritations or slight bronchitis, a dry hacking cough, complete loss of appetite, muscular and articular pains, gastric disturbances and general debility. The disease attacks particularly men under forty years of age, fewer women than men, and children scarcely at all.

The best preventives are fresh air, cleanliness, and constant disinfection. The disease is more amenable to careful dieting than to medicine.— (Boston M. and S. J.)

War Finance: As Viewed from the Roof of the World in Switzerland (letter written in September) —

The Spanish grippe, termed in Europe a mild form of cholera, has made its most notable impression at two distantly unrelated points, Berne in Switzerland, and Belfast in Ireland.

It knocked out the Swiss army, seventy-five thousand men under arms all the time now, but changed every two months. Switzerland maintains the proper ratio for defense — ten per cent. From her four million population, she can at any time summon four hundred thousand men to arms. But she had no defenses for the Spanish grippe which broke out here July 20, and soon filled every hospital to the limit and also nineteen hundred graves.

…In June and July there was slight comment in London upon a peculiar epidemic that would seize people so suddenly that, even at the theater, they had to be carried out. But there were few deaths from it, and if there were you would never hear of them in London.

…At Havre I first learned of the Spanish influenza as a deadly grippe. One of the leading English officials here permitted his orderly a visit to a sick sister in Belfast. When he returned the inquiry was as to his family, and he replied: “My sister was already buried, but I was in time to bury father and mother, two other sisters, five people next door and view thirty-three funerals on the way to the railroad station. Munition workers had to be called off to dig graves.”

Yet there were no reports in the public press. Ordinarily such an epidemic would have made columns in the newspapers. But when France loses men by the hundred thousand and permits no report and Germany after five millions of casualties has closed her list to the public early in 1917, and British war casualties steadily average seven thousand per day, epidemics, whether of influenza or cholera, are outclassed.

The antidote for Spanish influenza is said in France to be alcohol.

This lethargy changed practically overnight when influenza swept across Britain that autumn. It is estimated that between September and December of 1918, there were 12,000 deaths in London alone, and children began skipping to a pretty morbid nursery rhyme:

I had a little bird,

And its name was Enza.

I opened up the window,

And IN-FLU-ENZA.

By October, the Daily Mirror declared that “flu was tightening its grip on the country with as many as 1,000 patients clamouring for treatment at some north London surgeries and many doctors also down with the disease.” The severity of Spanish flu, where an otherwise healthy person could fall ill with what appeared to be mild influenza and then die unexpectedly, shook even the hardiest of doctors. Some victims–“big strong men, heliotrope blue and breathing 50 to the minute–would be fully conscious and clear-headed up to within half an hour of death, often not realising in the least how dire their condition was.” Others would slip into delirium, and still others–the “worst case by far”–were completely unconscious “hours or even days before the end, restless in his coma, with head thrown back, mouth half open, a ghastly sallow pallor of the cyanosed face, purple lips and ears.”

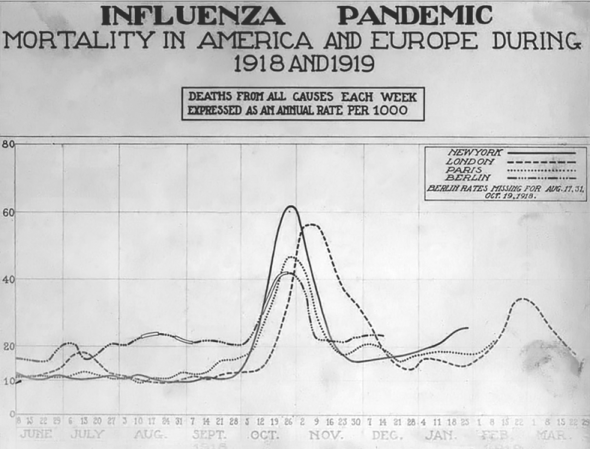

By November, the Spanish Flu struck down nearly every village and town in Britain: in Sheffield, there were nearly 200 deaths a week; in London the death rate was 55.5 per 1,000; in Liverpool 215; and in Manchester, during the peak in the final week of November, the death rate was 46 per 1,000.

Dr. James Niven, a Scottish physician and Manchester’s Medical Officer of Health, attempted to staunch the spread of Spanish flu in his city, and spread handbills and posters printed with advice on how to prevent and treat la grippe: avoid crowds, isolate oneself if one became ill, patients stay in bed, keep warm and call a doctor, discharges from mouth and nose should be destroyed, and those with even the mildest form of influenza should remain away from crowds for at least ten days.

Unfortunately, when news of the armistice reached Manchester Tuesday evening, everyone swarmed the streets in celebration, and continued partying into the next day. By Wednesday evening, the Manchester Evening News reported that the death toll had risen to 149, and the following days found reports of Manchester’s alarming numbers of deaths from Spanish flu.

In Niven’s Report on the Epidemic of Influenza in Manchester, 1918-1919, the outbreak was dreadful:

Mothers and fathers were often stricken together. The children, themselves ill, could not receive attention, and for a time it seemed as if it would not be possible to get coffins for the dead, or gravediggers to dig the graves… Bodies were left as long as a fortnight unburied, partly at home, partly at mortuaries, and partly at the premises of undertakers.

By the third wave of the flu (January-May 1919), authorities and health officials took the pandemic much more seriously, and medical specialists began to study the bacteria and its affects in order to understand just how and why the Spanish flu was so lethal. Questions that remained about the flu were why it affected the young and middle aged, whilst leaving the young and elderly relatively unscathed (however, Russia suffered from the reverse–children under 5 and adults over 65 were affected the worst), and why it virtually disappeared by autumn of 1919. Its cultural disappearance is also curious, as the letters collected by Richard Collier in The Plague of the Spanish Lady contain vivid and heartbreaking recollections from survivors of the pandemic–one would think that a disease that struck down so many and so quickly (and in America, shortened life expectancy by ten years!), and occurred within the 20th century, would remain as prominent in the history books as the 14th century Black Death. Nevertheless, it stands as an appalling bookend to the modern era’s first deadly war, and after its prominent role on Downton Abbey, it should not be forgotten.

Further Reading:

The Plague of the Spanish Lady: The Influenza Pandemic of 1918–19 by Richard Collier

Living With ‘Enza by Mark Honigsbaum

Epidemic and Peace, 1918 by Alfred W. Crosby

Britain and the 1918-19 influenza pandemic: a dark epilogue by Niall Johnson

Red Cross volunteers and the Spanish flu pandemic – British Red Cross

Flu: how Britain coped in the 1918 epidemic – The Independent

Influenza, 1918 – PBS’s American Experience

Spanish Influenza in North America, 1918–1919 – Harvard University Open Collection

The Flu Pandemic in Downton Abbey – Jane Austen’s World

Spanish Flu: The Forgotten Fallen – BBC docu-drama

Thanks for this — “Downton Abbey” was somewhat lacking in drama about the flu. I actually was sure they would kill off poor Lady Edith.

You shall see!

Why are nursery rhymes always so morbid?

That a world wide pandemic should strike in such a deadly fashion straight after WW1 surprises no one. Wars were always followed by famine and disease. But the flu largely affected the young and middle aged, whilst leaving the young and elderly relatively unscathed? That is the opposite of intuitive!

When the AIDS epidemic struck in c1981, I bet our oldest citizens were saying “here we go again… another killer disease”.

I asked my grandmother, now 100, whether she remembered the Influenza epidemic hitting their village in Italy. she didn’t seem to remember but when a visitor to the nursing home commented that she had heard Italians wore cloves of garlic around their necks to ward of disease, my grandmother replied that her Ma did. She said Ma was better than any doctor. Since my family all survived well into their 80s and 90s I’m going to take that as a true statement. It was such a terrible epidemic though. I have read a diary account of a young teenage girl and her younger sister in New England who had the ‘flu so badly they nearly died and one of an adult woman who had a mild case.

How interesting about the garlic. Most of the books I’ve read on the subject have mentioned that the flu was such a confusing disease, everyone had their own notions of a remedy or ward against it. I still shudder in horror over one passage, which described rows and rows of dead American soldiers, who returned from France relatively unscathed, only to die from the flu.

did they ever find a cure for this disease

I don’t believe they have. Scientists have studied and isolated the disease, but they haven’t fully solved what makes it tick, so to speak.