The Edwardian era appeared rife with social movements, but none caused as much furor as the “New Woman.” From Paris to London to New York to San Francisco, this phenomenon resulted in bitter denunciations, criticism and recriminations which thundered from pulpits to the Houses of Parliament.

The New Woman was a reaction against the long-held notions of femininity and the proper social sphere for women. This reaction was born, ironically, from the very reforms which were to enfranchise men. With schooling compulsory in the 1870s and 1880s, both boys and girls were given at least a basic education, which enabled them to find employment beyond the expectations of their parents’ generation.

As a result of the agricultural depression of the 1880s, young men and women, raised on tenant farms, or whose parents were employed by factories, found life insecure and uninspiring. Raised on the abundance of newspapers, periodicals and journals that proliferated in the late Victorian era, the lure of city life was difficult to resist. And so, for the first time, young women left their home for work, not in the traditional pursuit of domestic service, but as a professional.

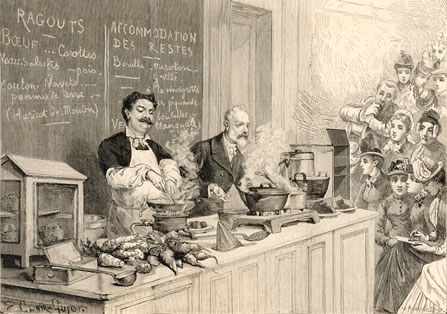

New technologies spread rapidly across the globe in the second half of the 19th century: the telephone, the telegraph, the elevator, the typewriter, the sewing machine, the cash register, etcetera. With these new technologies came jobs, and these jobs needed bodies to man them. Obviously, men were hired over women, but gradually, women began to make significant inroads in professional employment.

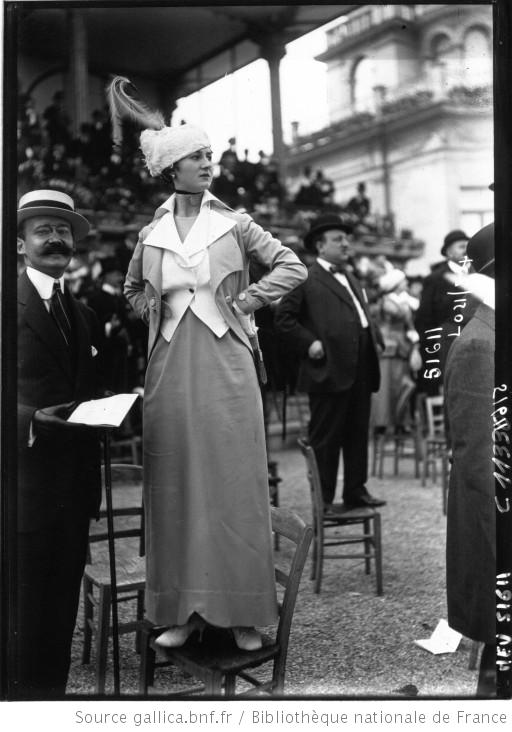

From the working girl of the period–perhaps a saleswoman, a secretary, telephone exchange operator–came the New Woman (or Gibson Girl, as she was characterized in the United States) who was personified by the shirtwaist, tall stiff collar, necktie, and heavy serge skirts she adopted as uniform. Perhaps she would ride her bicycle, which would require the scandalous bloomers!

These “New Women” were not content with their existence as “superfluous” women that characterized the mainstream press’s “woman problem”–that is, what to do with the increasing number of women who would never marry? This caused confusion over the gender role of women and led to a “tremendous debate over whether woman’s natural role was simply to procreate, or whether women should exercise the same range of choices men had.”

These questions and contradictions found a place in the fiction of the period, which was quickly called “New Woman literature.” Playwrights such as Henrik Ibsen and Arthur Wing Pinero wrote popular plays that put modern topics such as venereal disease, prostitution, and the role of marriage in the public eye, while authors like Annie Sophie Cory (Victoria Cross), Sarah Grand, Mona Caird, George Egerton, Ella D’Arcy and Ella Hepworth Dixon put a voice to the trials and tribulations of the New Woman.

Another segment of the New Woman was the “Bachelor Girl.” An advice book published during the era characterized the girl-bachelor as a “comfortable creature” and a “clever nest-builder.” More prevalent in American than Europe due to the vaster opportunities for women, the girl-bachelor was most often found in large American cities, sharing a flat or living in a boarding house with other working girls, and working in department stories, millinery shops, couturiers, as a secretary, a clerk, telephone exchange operator, waitress, hat-check girl, and a host of other supporting positions. Far from being old maids, the bachelor girl broke with traditional intersex relations, her financial and social independence putting her outside of the sphere of hearth and home.

Ultimately, the New Woman, the girl-bachelor, challenged and threatened, in the end shattering notions of proper gender roles for women. In reaction to this threat, there poured upon the heads of these women numerous satires in fiction, plays, cartoons and newspaper editorials of the “emancipated woman.” These scornful pieces of media claimed the New Woman had “unsexed” herself and lost the respect of men. They asked in response to “what does she want” with “what does she not want?”

She, according to an editorial in the New York Times, “dresses like a man, as far as possible, thereby making herself hideous…the next step will be to wear her hair short and adopt a mustache.” She also wants, “to work by man’s side and on his level and still be treated with the chivalry due her in her own kingdom–home and society–and any abatement of this treatment produces a storm of indignation and wrath quite beyond the sex she is endeavoring to emulate.” And that’s not the worst of the opinions.

The retaliation against the New Woman spilled onto the suffrage debate, creating more problems within the movement as not only man pit himself against woman, but woman versus woman as well. Despite this conflict, the New Woman was here to stay, and paved the road for the women of the post-war society.

Further Reading:

The New Woman

Henrik Ibsen and the New Woman

New woman novelists

Home Life in America by Katherine Graves Busbey

A word to women by Charlotte Eliza Humphry

The new girl: Girls’ Culture in England, 1880-1915 by Sally Mitchell

A new woman reader by Carolyn Christensen Nelson

Thanks for this site! I’m going to visit often — LOVE the Edwardian era, too!

-Eliza