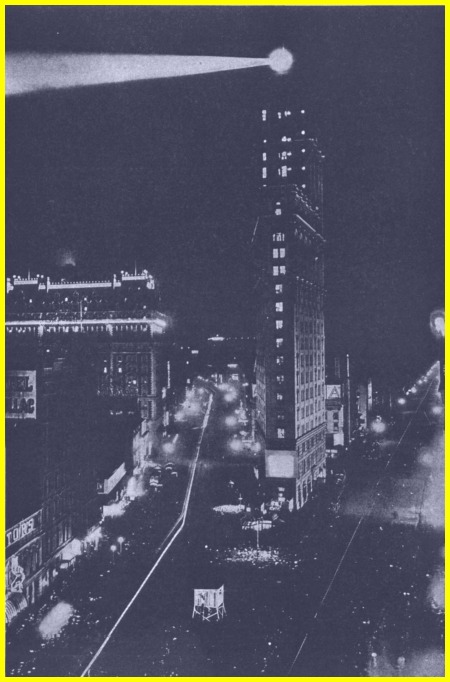

From the late 1890s through the 1910s, there emerged a spectacular, dazzling nightlife along Broadway. At that time, Broadway was a two mile stretch of din and dazzle between Madison and Longacre Square (renamed Times Square in 1904). One might rub shoulders with sparkling showgirls and squalid prostitutes, cops and confidence artists, panhandlers and the wealthiest men of Wall Street. Nicknamed the “Gay White Way” because of the never-ceasing splendor of lights from street lamps to marquee boards, the classic way to spend a night on Broadway began with cocktails, then to a show, then to one of the gaudy, extravagant “lobster palaces.”

From the late 1890s through the 1910s, there emerged a spectacular, dazzling nightlife along Broadway. At that time, Broadway was a two mile stretch of din and dazzle between Madison and Longacre Square (renamed Times Square in 1904). One might rub shoulders with sparkling showgirls and squalid prostitutes, cops and confidence artists, panhandlers and the wealthiest men of Wall Street. Nicknamed the “Gay White Way” because of the never-ceasing splendor of lights from street lamps to marquee boards, the classic way to spend a night on Broadway began with cocktails, then to a show, then to one of the gaudy, extravagant “lobster palaces.”

These “lobster palaces,” defined as “one of the elegant, expensive new restaurants that emerged in New York City, which specialized in lobsters and attracted the rich and famous,” catered to the theatrical crowds that nightly surged out of limousines, taxis and theatres in search of dinner or an after-theatre supper. And “lobster palace society,” comprised of playboys, professional beauties, stars such as Lillian Russell, chorus girls, kept women, sportsmen, newspaper men, celebrities of the Bohemia of the arts, and businessmen from the hinterlands. Beginning with the opening of Café Martin in 1899, the lobster palace, and its accompanying society both challenged and changed the components of New York society and its nightlife, proving a worthy ancestor of the “café society” of the 1920s and 1930s.

The first official lobster palace was Café Martin, which was opened in 1899 by Louis Martin, who had successfully operated a small hotel on Ninth St that was a favorite of French visitors. When he learned that Delmonico’s was vacating its site on Twenty-Sixth street to move uptown, he leased the building and created an intimate restaurant that introduced side-by-side eating known as a banquette. This cozy atmosphere was very attractive to men who wished to entertain young women who were not their wives and not surprisingly, Café Martin became the rendezvous of the smart set for luncheons and dinners. Another beguiling feature was his dining terrace, which was placed just above the street and covered with a brightly striped awning. Seated behind shrubs, flowering plants, and palms, guests could admire the splendid view of Madison Square without being seen. Martin hired an orchestra for his cafe and allowed women to dine there if escorted, and even served drinks to them (cafes normally operated as masculine preserves).

Café Martin was quickly followed by the Café des Beaux Arts, founded by a former employee of Martin, Jacques Bustanoby, and his two brothers. Located a Forty-Second and Sixth, Bustanoby’s restaurant was immediately popular with theatergoers and the headliners of the shows. The attraction for the theatre stars were the soirees artistique, which Jacques cajoled them into performing. Lillian Russell, for example, would enter the restaurant to applause and in the company of Jesse Lewishon, Diamond Jim Brady and his wife Edna, and producer Florenz Ziegfeld and his wife, Anna Held, and it was in this restaurant that Lillian and Diamond Jim, both famous for their girths and appetites, wagered that if she could match him course for course, he would give her a huge diamond ring the following day. According to Bustanoby, Lillian slipped into the ladies’ room and came out with a heavy bundle under her arm, wrapped in a tablecloth. She told the proprietor to keep it for the next day and then returned to the table and ate plate-for-plate, beating Jim fair and square.

Café Martin was quickly followed by the Café des Beaux Arts, founded by a former employee of Martin, Jacques Bustanoby, and his two brothers. Located a Forty-Second and Sixth, Bustanoby’s restaurant was immediately popular with theatergoers and the headliners of the shows. The attraction for the theatre stars were the soirees artistique, which Jacques cajoled them into performing. Lillian Russell, for example, would enter the restaurant to applause and in the company of Jesse Lewishon, Diamond Jim Brady and his wife Edna, and producer Florenz Ziegfeld and his wife, Anna Held, and it was in this restaurant that Lillian and Diamond Jim, both famous for their girths and appetites, wagered that if she could match him course for course, he would give her a huge diamond ring the following day. According to Bustanoby, Lillian slipped into the ladies’ room and came out with a heavy bundle under her arm, wrapped in a tablecloth. She told the proprietor to keep it for the next day and then returned to the table and ate plate-for-plate, beating Jim fair and square.

The bundle she handed to Bustanoby was her corset.

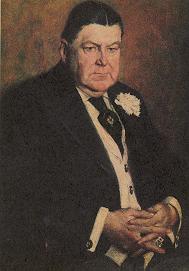

“Diamond Jim’s” given name was James Buchanan Brady, and though a successful financier, he was most known for his love of the items which gave him his name, and his astounding appetite. It was not unusual for Brady to eat enough food for ten people at a sitting. A typical Brady breakfast would be: eggs, pancakes, pork chops, cornbread, fried potatoes, hominy, muffins, and a beefsteak. For refreshment, a gallon of orange juice—or “golden nectar”, as he called his favorite drink. Lunch might be two lobsters, deviled crabs, clams, oysters and beef, with a few pies for dessert. The usual evening meal began with an appetizer of two or three dozen oysters, six crabs, and a few servings of green turtle soup, followed by a main course of two whole ducks, six or seven lobsters, a sirloin steak, two servings of terrapin and a host of vegetables. For dessert, the gourmand enjoyed pastries and a two pound box of candy.

Lillian Russell, his longtime amour–though the actual details of their relationship (romantic or platonic?) are murky–“airy, fairy, Lillian, the American Beauty”–after whom America’s favorite rose was named–whose hourglass (while corseted) figure with its ample hips and very full bosom weighed 200 pounds; she was the Belle Epoque ideal. She was known equally for her legendary beauty, her voice and stage presence, and her appetite, as it was said she ate more than Diamond Jim! Whatever the case was, restaurateurs and maitre d’hotels sighed in ecstasy alike when the two descended upon a lobster palace after a performance, with Rector’s being the ideal place.

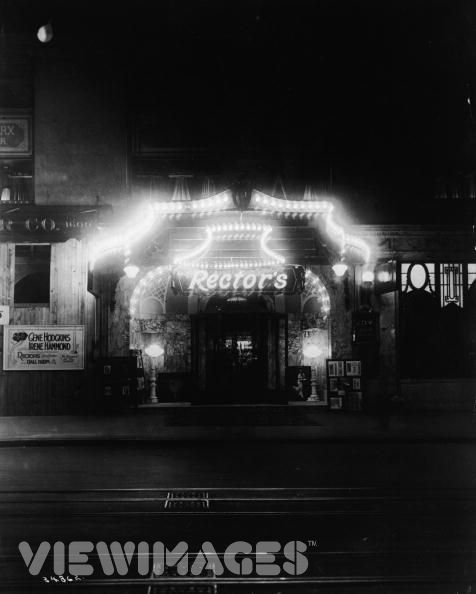

Rector’s, though making its debut in New York City after the restaurants of Bustanoby and Martin, was the premiere lobster palace. Though sharing fame with such entities as Shanley’s and Murray’s Roman Gardens, etc in terms of opulence and grandeur, something about Rector’s placed it ahead of the crowd. It didn’t help either that everybody went to Rector’s.

Lobster palace society indulged itself in a healthy exhibitionism which led to its most characteristic ceremony, the “entrance.” At no other place could one make an entrance as at Rector’s. A sturdy, imposing building of Greco-Roman design, the interior was breathtaking, Charles Rector lavishing $200,000 to transform the interiors into a mirrored paradise of green and gold, providing linen especially woven in Dublin, hand-stenciled silver covered a hundred tables on the ground floor and seventy-five on the second. Four private dining rooms completed the interiors. In a neat coup before opening, Rector wooed saucier Charles Parrandin, the maitre d’hotel Paul Perret and the business manager Andrew Mehler from Delmonico’s. His staff of 165 were impeccable, most having graduated from professional schools in Switzerland and though the hours were grueling (10 am to 3 am with three hours off in the afternoon) and the salary meager ($25 dollars weekly), Rector’s was the place to be for both patrons and employees alike.

Lobster palace society indulged itself in a healthy exhibitionism which led to its most characteristic ceremony, the “entrance.” At no other place could one make an entrance as at Rector’s. A sturdy, imposing building of Greco-Roman design, the interior was breathtaking, Charles Rector lavishing $200,000 to transform the interiors into a mirrored paradise of green and gold, providing linen especially woven in Dublin, hand-stenciled silver covered a hundred tables on the ground floor and seventy-five on the second. Four private dining rooms completed the interiors. In a neat coup before opening, Rector wooed saucier Charles Parrandin, the maitre d’hotel Paul Perret and the business manager Andrew Mehler from Delmonico’s. His staff of 165 were impeccable, most having graduated from professional schools in Switzerland and though the hours were grueling (10 am to 3 am with three hours off in the afternoon) and the salary meager ($25 dollars weekly), Rector’s was the place to be for both patrons and employees alike.

On to the “entrance”:

The time is somewhere between eleven thirty and midnight. The orchestra is playing, when it is suddenly called to a halt. The leader has caught sight of a star just about to enter (if she is not a star recognizable on sight, he has probably been tipped off in advance as to her identity). There is a pause of silence during which all conversation ceases. Then the orchestra strikes up the song currently associated with the star who, blushing faintly, glides swanlike to her table, skin dazzling, diamonds winking, profile at the proper tilt. Her escort, probably hidden behind the blanket of violets, her evening’s tribute, knows his name will go down in

history.

By the 1910s, competition for patronage became fierce, particularly after the ragtime dance craze swept across both sides of the Atlantic. As restaurateurs and patrons sought new diversions, into America came the cabaret. Initially existing on the fringes of New York society, and mainly known through Parsian caf-concs of the 1890s, the cabaret first reached beyond the vice districts to the attention of respectable New Yorkers in the spring of 1911 when Henry B. Harris and Jesse Lasky, two vaudeville entrepreneurs, opened the Folies Bergère Theater on Forty-Ninth in the heart of the theatre district. Two shows a night were offered: first, an elaborate revue from 8 pm to 11 pm, and an after-theater cabaret performance from 11:15 pm to 1 am. The two promoters introduced a champagne bar, a balcony promenade, and the first American midnight performance. Soon after its opened though, the Folies suffered a financial decline. Offering only 700 seats, the theatre could not sustain its huge redecoration costs and entertainment investment. Designed as a theatre-restaurant, the Folies’ two elements didn’t work well together. The restaurant only comprised 41% of the floor plan.

Nonetheless, people latched onto the idea of supper, dancing and a show, and by late 1911 and early 1912, a number of lobster palaces picked up the cabaret idea and began experimenting with the presentation of entertainment along with the sale of food and drink. Jacques Bustanoby opened the Domino Room at Columbus Circle and introduced midnight ’til dawn dancing. Reisenweber’s, which could claim to have introduced cabaret to America, had four rooms and a ballroom. At various times, it had its large restaurant divided into the 400 Room–where the Dixieland Jazz Band were introduced –, the Sophie Tucker Room and the Doraldina Hawaiian Room–was the first in New York to echo with the pitter-pat of turkey-trotting feet–, all offering patrons a choice of environments. Later cabaret/lobster palaces were The Midnight Frolic and the Century Roof (Cocoanut Grove), who charged relatively expensive covers of $1-2 for a couple without drinks! Once inside, drinks cost 25 cents for cocktails and highballs, $2.50 for a pint of champagne, five dollars for a quart. Sans Souci, founded by Vernon and Irene Castle, was the first cabaret not associated with a preexisting lobster palace. Designed after Parisian models, the club opened Dec 1913 in a basement on 42nd Street. Other places followed suit, opening special cabaret establishments. Finally, theatres converted their roof gardens to cabarets and ballrooms.

Dancing girls were the sole attraction of this first show, and within two weeks every lobster palace with a dance floor had a chorus line. At first, the development of the floor was almost accidental, as restaurants merely followed Lasky and Harris’s policy of presenting a few entertainers as incidental diversions. restaurant managers would hire a few special intimate acts, such as singers and dancers, from rathskellers or the lower rungs of vaudeville and have them circle among the tables as incidental attractions to the dining and drinking. Rather than putting up stages, the restaurants cleared a space in the dining room or installed small platforms. It was only after 1915, after the ragtime dance craze had made the cabarets profitable that owners were convinced of their earning potential and began to implement more elaborate stages.

The seating of patrons at tables was the other distinctive feature of the cabaret, one that encouraged greater intimacy between audience and performers and among the audience itself. Guests watched the entertainment from dining chairs at tables. As the years went by, the size of meals declined as guests spent their time watching the acts or dancing, but the restaurant setting and the table continued as an important locus for patrons’ dining, drinking and personal interactions.

Lobster palaces died with the closing of the Great War, and despite efforts to revive the old restaurants of both lobster palace society and the Four Hundred, society had changed too much. Most notably was the sudden popularity of Harlem in the 1920s, and finally, Prohibition, which put many legitimate restaurants out of business who were unable to sustain profitability without the sale of liquor.

Further Reading:

On the Town in New York by Michael Batterberry & Ariane Batterberry

Diamond Jim Brady by Harry Paul Jeffers

Empire City by Kenneth T. Jackson, David S. Dunbar

Steppin’ Out by Lewis A. Erenberg

Welcome to our city by Julian Street

Incredible New York: High Life and Low Life of Last Hundred Years by Lloyd R. Morris

A great description of the Lobster Palace! I cited this page at http://maine-lobster.com/lobster-facts

Thanks!!