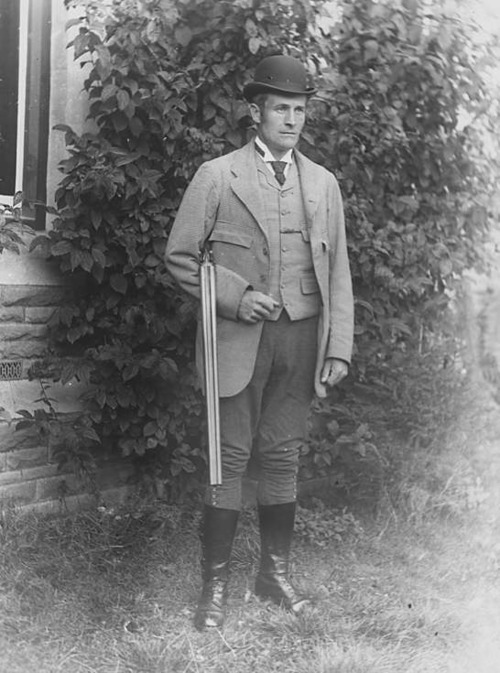

The position of a gamekeeper in England is a curious one. Admittedly he is among the most skilled and highly trained workers of the The country-side. His intimate knowledge of wild life commands respect. Often he is much more than a careful and successful preserver of game—a thoroughly good sportsman, a fine shot. His work carries heavy responsibility; as whether a large expenditure on a shooting property brings good returns—and on him depends the pleasure of many a sporting party. On large estates he is an important personage—important to the estate owner, to the hunt, to the farm bailiff, and to a host of satellites. His value is proved by the many important side-issues of his work—dog-breeding and dog-breaking, or the breaking of young gentlemen to gun work. Yet, in spite of the honourable and onerous nature of his calling, he is paid in cash about the same wage as a ploughman.

The actual wages of a first-class gamekeeper may be no more than a pound a week. A system has sprung up by which he receives, in addition to wages, many recompenses in kind, while his slender pay is fortified by the tips of the sportsman to whom he ministers. This system has bred in him a kind of obsequiousness—he is dependent to a great extent on charity. With a liberal employer he may be well off, and all manner of good things may come his way; but with a mean employer the perquisites of his position may be few and far between.

At the best, he may live in a comfortable cottage, rent free. His coal is supplied to him without cost, and wood from the estate. Milk is drawn freely from the farm—or he may have free pasturage for a cow of his own. A new suit of clothes is presented to him each year. He may keep pigs for his own use, usually at his own expense, but this is a small item, and even here he may be helped out by a surplus of pig-food from the kitchen of the house or from the farms. He has a fair chance to make money by dog-breeding and exhibiting. Then there is vermin and rabbit money which he earns as extra pay, and useful sums may flow into his pocket from the hunt funds.

He may keep fowls at his employer’s expense, and if not solely for his own use, he has the privilege of a proportion of the eggs, and a reasonable number of the chickens may be roasted or boiled for his own table. The estate gardeners aid him with his gardening operations, and many surplus plants and seeds find their way into his plot. To rabbits he may help himself freely, also to rooks and pigeons. After each shooting party his employer—if a generous master—invites him to take home a brace of pheasants and a hare; and there may be other ways in which game comes to his larder.

Commissions and fees of various indeterminate sorts may swell his coffers. All kinds of supplies he secures, if not freely, at reduced prices. And always there is the harvest of tips. Clearly there is every chance for a gamekeeper to receive charity of some form or another, if it is not always offered; and this must tend to weaken that independence which is found by the man who is paid for his labour fairly and squarely in cash.

Wood-pigeons are among the gamekeeper’s perquisites. Apart from a very occasional request from “the house” for the wherewithal for pigeon-pie, the pigeons shot are for the benefit of the keeper and his family, and when he shoots more than he requires there are always labourers and others glad of a pigeon or two “to make a pudden.” Rabbits, also, are perquisites, but to be sold no more than pigeons. The popular idea is that keepers may help themselves to any game they please—true, they could if so minded. But no matter what a keeper’s ethics in other directions, as a rule he deals honourably with the game in his charge. The keeper has no more right to take a brace of birds or a hare without permission than has an ironmonger’s assistant to take a coal-scuttle.

Gamekeepers, though their work for wages is never done, yet have a few legitimate ways of adding to their incomes. Of course they have the opportunity of making a good deal of money if they trespass on their employers’ time; but your keeper is an honest man, and his work is the object of his life. Most keepers are skilled vegetable gardeners, and may make a few shillings from peas and beans. Often enough they have a cunning way with flowers, though envious amateurs are free with their hints about the advantages to be gained from burying foxes to enrich the soil. We know one who will put in a fair day’s work with spade and wheelbarrow before even the waggoners have stirred to give their horses breakfast. Going his rounds, the keeper marks good briers for budding; if he does not sell them, he will beg choice buds from rose-growers, and a year or two later the passer-by may be tempted to offer half-a-crown for the fine roses of his little plot.

For the first time in many a long year a gamekeeper may find himself taking a holiday in the early days of February—either because he has left his place of his own free will, or has been dismissed. “Left owing to shoot being given up “—that is the usual reason for a keeper’s enforced holiday. Married keepers seldom leave berths of their own accord except to better themselves; but a young bachelor keeper with a light heart may be fond of change, and scores of places are open to him from which married men are barred. Often he can afford to take a holiday while he looks about for a new berth; he can find lodgings anywhere, and what with odd jobs and the money he has saved he can exist comfortably until he finds an employer to suit him.

The married keeper is not so light-hearted, and perhaps on this account the best permanent berths go to the married men. The chance of such a berth gives the country maiden her best chance of bagging an elusive bachelor. Sometimes she captures the heart of a bachelor before he has found a berth that will support a wife; then he will advertise for a place, making the ambiguous statement: “Married when suited.” No doubt some keepers who have issued this form of advertisement could tell strange stories of the applications received.

— A Gamekeeper’s Notebook by Owen Jones & Marcus Woodward

Comments are closed.