Every other Saturday, I am opening the doors of Edwardian Promenade to authors whose work will interest readers of the blog. If you are an unpublished novelist, or have a new or upcoming release that deals with American or English society between the years 1880 and 1945, contact me for more information!

AUTHOR NAME: M.K. Tod

BOOK TITLE: Unravelled

DESCRIPTION: Two wars, two affairs, one marriage. In October 1935, Edward Jamieson’s memories of war and a passionate love affair resurface when an invitation to a WWI memorial ceremony arrives. Though reluctant to visit the scenes of horror he has spent years trying to forget, Edward succumbs to the unlikely possibility of discovering what happened to Helene Noisette, the woman he once pledged to marry. Travelling through the French countryside with his wife Ann, Edward sees nothing but reminders of war. After a chance encounter with Helene at the dedication ceremony, Edward’s past puts his present life in jeopardy. When WWII erupts a few years later, Edward is quickly caught up in the world of training espionage agents, while Ann counsels grieving women and copes with the daily threats facing those she loves. And once again, secrets and war threaten the bonds of marriage. With events unfolding in France, England and Canada, UNRAVELLED is a compelling novel of love, duty and sacrifice set amongst the turmoil of two world…

WWI JOURNALS MIGHT HAVE BEEN THE EQUIVALENT OF BLOGS

In May 2009 while researching WWI Paris, I found three journals that vividly brought the home front experience to life. These were On the Edge of the War Zone by Mildred Aldrich, Fighting France by Edith Wharton and Paris War Days by Charles Inman Barnard. At that time, Aldrich and Barnard were journalists, Wharton already a well-known novelist. These were people who had lived through it and written about their experiences with great regularity. Excitement bristled as, pen in hand, I read every single word.

When publishing his diary, Charles Inman Barnard stated his intent very clearly: “These notes … are published with the idea of recording, day by day, the aspect, temper, mood, and humor of Paris, when the entire manhood of France responds with profound spontaneous patriotism to the call of mobilization in defense of national existence.” His diary begins on Saturday, August 1, 1914 and continues until Wednesday, September 16, 1914. My copy is full of underlining and margin notes.

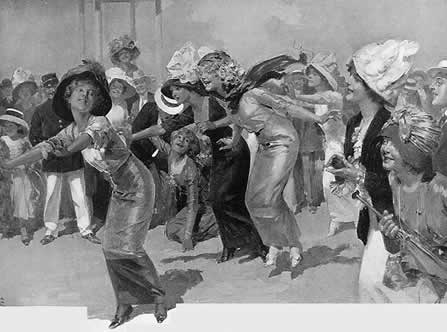

After mobilization notices were posted on August 1, 1914 – “Crowds of young men, with French flags, promenaded the streets, shouting ‘Vive La France!’ Bevies of young sewing girls collected at the open windows and on the balconies of the Rue de la Paix, cheering, waving their handkerchiefs at the youthful patriots, and throwing down upon them handfuls of flowers and garlands that had decked the fronts of the shops.”

As mobilization proceeds and war is declared young men disappear from the streets of Paris. Servants head off to war. Vehicles, including bicycles, are requisitioned. Rioters smash shops owned by Germans, curfews are imposed. At night “[n]o one was allowed to loiter. To wait five minutes outside a house was to court investigation and possibly arrest. There was no sound except that of footfalls and a low murmur of conversation.”

Breakfast rolls are no longer produced. Milk is rationed. Telephone conversations must be in French. Telegrams must be authorized. Wireless installations are forbidden. Prisoners charged with light offenses are allowed to enlist. Versailles becomes a gathering spot for the army. Women train to become nurses. New regulations are enacted for war correspondents. Cafes are forbidden from selling absinthe. Race courses at Auteuil and Longchamp are “turned into large grazing farms for sheep and cattle requisitioned by the military authorities.”

Beyond these observations of day-to-day life, Barnard reports on political events, German advances, French military affairs and the heavy fighting occurring throughout Belgium and France. Unfortunately, France is outnumbered and out-generaled. On September 2nd, Poincare moves the French government to Bordeaux telling his countrymen and women to ‘fight and stand firm’. By September 16th the German advance is finally stopped and Paris heaves a sigh of relief.

Edith Wharton was one of the few foreigners allowed to travel to the front lines during WWI but she begins her journal with The Look of Paris, recording observations about that city from July 30, 1914 to February 1915. Her journal is just as compelling as her novels. In August she writes: “War, the shrieking fury, had announced herself by a great wave of stillness … Paris scorned all show of war, and fed the patriotism of her children on the mere sight of her beauty. It was enough.”

Like Barnard, Wharton records the unfolding of regulations, the advent of refugees, and the reactions of citizens and soldiers to war. By February she received permission to visit the Argonne. “Along the white road rippling away eastward over the dimpled country the army motors were pouring by in endless lines, broken now and then by the dark mass of a tramping regiment or the clatter of a train of artillery.” Entries from that region of France as well as later trips reveal a country in the midst of war: a town where “nothing was left but a brick-heap and some twisted stove-pipes”; a field hospital where all was “monastic shades of black and white and ashen grey”; a night in Verdun when “the hush was so intense that every reverberation from the dark hills beyond the walls brought out in the mind its separate vision of destruction”; the large village of Laimont “wiped out as if a cyclone had beheaded it”; a red flash of a bomb followed by a “white light [that] opened like a tropical flower, spread to full bloom and drew itself back into the night”.

In May 1915 Wharton is in Lorraine and the Vosges and she writes of “murdered houses” and a town “spread out in its last writhings”, and of Gerbeville where the “ruins seem to have been vomited up from the depths and hurled down from the skies, as though she had perished in some monstrous clash of earthquake and tornado.”

The entire journal is riveting.

In the spring of 1914, Mildred Aldrich moved to the small village of Huiry overlooking the Marne river valley. She was sixty-one years old. On the Edge of the War Zone takes the form of letters and follows an earlier volume called A Hilltop on the Marne where she explains to the recipient of her letters that she moved away from Paris because she felt the “need of calm and quiet – perfect peace”. Aldrich had no idea that the war would be on her doorstep a few months later.

Through her eyes we see a village coping with life in close proximity to fierce fighting. Often they have no information about what’s taking place and try to piece together clues from “thin ribbons of smoke” or the intermittent sounds of booming cannons or the occasional passing troop of soldiers.

In November 1914 Aldrich tells her friend that “we have settled down to a long war, and though we have settled down with hope, I can tell you that every day demands its courage.” In December she is offered a trip by motorcar to see a few villages in the area. Along the way Mildred and her companions stop to walk across a field full of graves. “[T]he boys lie buried just where they fell—cradled in the bosom of the mother country that nourished them, and for whose safety they laid down their lives … we reached a point where, as far as the eye could see, in every direction, floated the little tricolore flags, like fine flowers in the landscape.”

As winter unfolds, Mildred Aldrich reflects on fresh disasters like the use of gas and the destruction of the Lusitania. German gas attacks change the French people. “Their faces had become more serious, their bearing more heroic, their laughter less frequent, and their humor more biting.” According to Aldrich, an awful hatred arose.

Throughout 1916 regiments billet in Huiry and Aldrich learns much about the duties of soldiers and their activities when resting behind the lines. This series of letters ends when the United States enters the war in April 1917 but is followed by two further collections: The Peak of the Load and When Johnny Comes Marching Home.

Beyond Barnard, Wharton and Aldrich I found A Village in Picardy by Ruth Gaines, Home Fires in France by Dorothy Canfield, You Who Can Help by Mary Smith Churchill, and Letters of Agar Adamson, a collection edited by Norm Christie. Collectively these memoirs provide an unvarnished look at war through the eyes of everyday people and have offered insights and inspiration for the three novels I have set during WWI. But beyond that they offer any reader an honest appraisal of what occurs when nations set out to conquer other nations.

I wonder whether these writers might have been bloggers in today’s world. Tweets would not have sufficed for the depth of information they provide and their reflections about the people and circumstances of war.

M.K. Tod writes historical fiction and blogs about all aspects of the genre at A Writer of History. Her debut novel, UNRAVELLED: Two wars. Two affairs. One marriage. is available in paperback and e-book formats from Amazon (US, Canada and elsewhere), Nook, Kobo, Google Play and soon on iTunes. Mary can be contacted on Facebook, Twitter and Goodreads.

I would love to read those journals, particularly Edith Wharton’s. I’m working on a book set in 1919 Sacramento, but the family has connections to WWI. I’ve bookmarked this post for my research.

What interested me as well, Elizabeth is that they are so well written. Wharton’s prose for example is almost as fine as her novels. Good luck with your research.

“Breakfast rolls are no longer produced. Milk is rationed. Telephone

conversations must be in French.” – Details, details. It’s these kinds of little details that contribute so much to creating authenticity in historical fiction. The letters people wrote, the journals they kept. Thanks for sharing the specifics of these critical resources you found for research and writing UNRAVELLED, Mary!

These journals are truly fascinating, Carol. Of course, I’m totally obsessed!

Thank you.. I am always looking for WW1 writing that was not written published by our governments’ Departments of War.

You were very fortunate in researching the WWI experience in Paris that you found three contemporary journals that survived and were published. The practice of censorship was pervasive at the time, at least in the armed forces, and even photographers had to be registered and approved. Even personal letters tended to be thrown out over the years 🙁

In reading the book Australians at the Western Front – Fromelles 1916, I was constantly in tears reading the diaries and letters. They were so personal, so immediate, so painful! http://melbourneblogger.blogspot.com.au/2013/09/australians-at-western-front-fromelles.html

Thanks for stopping by from Melbourne. I agree with you about being in tears over some diaries and letters. I wonder whether Wharton, Aldrich and Barnard were able to bypass the censors because of their American status? Thanks also for the link and information about Fromelles. The senselessness astounds me.