Nothing preoccupied the mind of an Edwardian hostess so much as the planning of a dinner party. From matters of food and drink, table service, the guest list, and matters of precedence, every detail was of the utmost importance. A dinner of tepid or cold food, of dull guests, and of seating arrangements that did not take the rank and form of each guest into account could doom a lady’s social aspirations in one evening.

Nothing preoccupied the mind of an Edwardian hostess so much as the planning of a dinner party. From matters of food and drink, table service, the guest list, and matters of precedence, every detail was of the utmost importance. A dinner of tepid or cold food, of dull guests, and of seating arrangements that did not take the rank and form of each guest into account could doom a lady’s social aspirations in one evening.

Since dinner giving was the most important of all social observances, gentlemen and their wives held them much more frequently than balls or other social occasions; a dinner was considered more intimate, and invitations were sent to those one was intimate with or with those the host and hostess hoped to become intimé. In the greater scheme of the inner workings of society, a dinner party was both a test of the hostess’s position and the direct road to obtaining a recognized place in society.

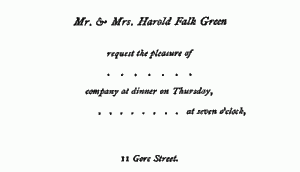

When issuing invitations to a large dinner party, it was customary for the hostess to give three weeks’ notice, though, by the 1910s, the notice was extended to four to six weeks in advance. This permitted sufficient time for the guests to bow out in case of an emergency–though the acceptance of the invitation was socially binding. Invitations could be purchased at stationary shops, and were blank save for lines where the hostess or her social secretary would fill in the names of the guests, the date, and the time of the dinner. These were sent in the name of both the host and hostess as following:

The dinner hour was approximately eight to nine, and guests were expected to appear at least fifteen minutes prior to the time listed on the invitation. The long, slow, and heavy meals of the mid-nineteenth century had disappeared by the Edwardian era: now hostesses preferred their dinner parties swift and filling (though this was taken to the extreme by Gilded Age hostess Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish, who would hurry her guests through eight or nine courses in forty minutes), most likely to make time for evening entertainments.

On arrival, ladies and gentlemen would take off their cloaks in the cloakroom or leave them in the hall with the servant before entering the drawing-room, where the host and hostess awaited them. The vogue for pre-dinner cocktails was strictly an American custom until about 1910, and once the host and hostess greeted each guest, the ladies sat and the men stood, chatting lightly until the last guest had arrived. If any parties were unacquainted, the hostess would introduce the guests of the highest rank to one another. At very large dinner parties, however, the butler was stationed on the staircase and announced the guests as they arrived, and no introductions were required.

On arrival, ladies and gentlemen would take off their cloaks in the cloakroom or leave them in the hall with the servant before entering the drawing-room, where the host and hostess awaited them. The vogue for pre-dinner cocktails was strictly an American custom until about 1910, and once the host and hostess greeted each guest, the ladies sat and the men stood, chatting lightly until the last guest had arrived. If any parties were unacquainted, the hostess would introduce the guests of the highest rank to one another. At very large dinner parties, however, the butler was stationed on the staircase and announced the guests as they arrived, and no introductions were required.

According to Arnold Palmer’s Moveable Feasts: Changes in English Eating Habits, the custom of pairing off to go in for dinner did not begin until early in the reign of William IV, and this was refined throughout the nineteenth century until it morphed into its usual form: The host would take the lady of the highest rank present in to the dinner, and the gentleman of the highest rank took in the hostess. This rule was absolute, unless the highest ranking male and female were related to the host or hostess, in which case his or her rank would be in abeyance, out of courtesy to the other guests.

Another don’t was for a husband and wife, father and daughter, or mother and son, to be sent in to dinner together. The hostess was advised to invite an equal number of men and women, though it was usual to invite two or more gentlemen than there were ladies, so that married ladies would not be obligated to go in to dinner with each others’ husbands only. Should the numbers be skewed, if there were more women than men, the ladies of highest rank would be taken into dinner by the gentlemen present, and the remaining ladies followed by themselves. In there were more men than women, the hostess would go in to dinner by herself, following the last couple. Prior to entering the dining room, the hostess would inform each gentleman whom he would take in to dinner.

The host remained standing until the guests had taken their seats, and he motioned to each couple where he wished them to sit. When the host did not indicate where the guests were to sit, precedence took over, and each lady and gentleman sat near the host or hostess according to their rank. The host and the lady he took in to dinner sat at the bottom of the table, she sitting at his right hand. The hostess sat at the top of the table, and the gentleman who brought her in to dinner sat at her left. According to precedence, the lady second in rank sat at the host’s left hand, and the other female guests sat at the right of the gentleman who took her in to dinner. Place cards with the names of each guest were used at large dinner parties, and in some instances, the name of each guest was printed on a menu and placed in front of each cover. The menus themselves were placed along the table, each viewable by one or two persons. These menus could be simple or elaborate, depending on the hostess’s tastes, and the dishes available in each course were written in French.

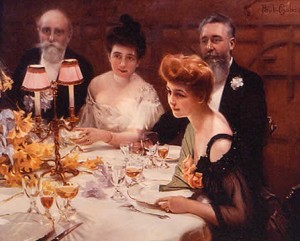

For table decoration, there were a number of variations available, though they were largely a matter of taste than of etiquette. The basic table setting was of a mixture of high and low center pieces, low specimen glasses placed the length of the table, and trails of creepers and flowers laid on the tablecloth. The fruit to be eaten for dessert was usually arranged down the center of the table, amidst the flowers and plate. Some dinner tables were decorated with a variety of French conceits (centerpieces), whilst others were sparse, save for the flowers and the plate. Lighting was an important feature, and though electric lights were in vogue when possible, it was not uncommon to dine by old-fashioned lamps and wax candles. Accompanying the decorations and lighting was the “cover,” which was the place laid at the table for each person, and consisted of a spoon for soup, a fish knife and fork, two knives, two large forks, and glasses for the wines being served.

For table decoration, there were a number of variations available, though they were largely a matter of taste than of etiquette. The basic table setting was of a mixture of high and low center pieces, low specimen glasses placed the length of the table, and trails of creepers and flowers laid on the tablecloth. The fruit to be eaten for dessert was usually arranged down the center of the table, amidst the flowers and plate. Some dinner tables were decorated with a variety of French conceits (centerpieces), whilst others were sparse, save for the flowers and the plate. Lighting was an important feature, and though electric lights were in vogue when possible, it was not uncommon to dine by old-fashioned lamps and wax candles. Accompanying the decorations and lighting was the “cover,” which was the place laid at the table for each person, and consisted of a spoon for soup, a fish knife and fork, two knives, two large forks, and glasses for the wines being served.

Dinner-table etiquette was strict–an uneducated or uncouth person who appeared innocuous enough, would reveal his or her inexperience in a finer milieu by displaying such shocking customs as eating off a knife, or tucking a napkin into the collar of their shirt. When a lady took her seat at the dinner table, she removed her gloves at once, though were long gloves, they were usually made to allow the glove to be unbuttoned around the thumb and peeled back from the wrists. Both ladies and gentlemen would unfold their serviettes and place them in their laps.

Soups were, of course, eaten with a soup spoon, though one spooned away from themselves and never ever slurped. Fish was eaten with the fish knife and fork, and all made dishes (quenelles, rissoles, patties, etc) were eaten with a fork only. Poultry, game, etc were eaten with a knife and fork, as was asparagus and salads. Peas, the test of true breeding, were eaten with a fork. In eating game or poultry, the bone of either wing or leg was not touched with the fingers; the meat was cut from the bone with the knife. Jellies, blancmanges, ice puddings, and practically any substantial sweet, were eaten with a fork. Cheese was eaten daintily, with small morsels placed with the knife on small morsels of bread, and the two conveyed to the mouth with the thumb and finger. When eating grapes, cherries, or other pitted fruits, they were brought to the mouth, whereupon the pits and skins were spit discreetly into the hand to be placed on the side of the plate.

Dessert was served to the guests in the order in which dinner was served. When the guests had helped themselves to the wine and the servants had vacated the dining room, the host would hand the decanters around the table, starting with the gentleman nearest him, as ladies were not supposed to require a second glass of wine during dessert. If she required a second glass, the gentleman seated beside her would fill the glass–she would definitely not help herself to the wine. Ten minutes or so after the wine had been passed once around the table, the hostess gave a signal for the ladies to leave the dining room by bowing to the lady of the highest rank present. The gentlemen rose when the ladies did, and the women quit the dining room in the order of their rank, the hostess following last. The gentlemen were left to their port and claret, while the ladies retired to the drawing room for coffee. While the ladies drank their coffee, a servant took the coffee to the gentlemen, and after a few more rounds of wine and the cigarettes and cigars were smoked, they joined the ladies. This custom, however, shortened by 1910 or so, and at times, the practice of ladies and gentlemen separating after dinner was abandoned by smarter hostesses.

Dessert was served to the guests in the order in which dinner was served. When the guests had helped themselves to the wine and the servants had vacated the dining room, the host would hand the decanters around the table, starting with the gentleman nearest him, as ladies were not supposed to require a second glass of wine during dessert. If she required a second glass, the gentleman seated beside her would fill the glass–she would definitely not help herself to the wine. Ten minutes or so after the wine had been passed once around the table, the hostess gave a signal for the ladies to leave the dining room by bowing to the lady of the highest rank present. The gentlemen rose when the ladies did, and the women quit the dining room in the order of their rank, the hostess following last. The gentlemen were left to their port and claret, while the ladies retired to the drawing room for coffee. While the ladies drank their coffee, a servant took the coffee to the gentlemen, and after a few more rounds of wine and the cigarettes and cigars were smoked, they joined the ladies. This custom, however, shortened by 1910 or so, and at times, the practice of ladies and gentlemen separating after dinner was abandoned by smarter hostesses.

Dinner ended in town about half an hour after the gentlemen joined the ladies in the drawing room. In the country, it was common to begin games or play cards into the wee hours of the night. There was no etiquette for leave-taking, and after the host and hostess saw each guest into his or her or their carriages, their duties were done for the night.

Further Reading:

Manners and Rules of Good Society by A Member of the Aristocracy

Manners and Social Usages by Mrs. John Sherwood

Etiquette of Good Society by Lady Colin Campbell

The Correct Thing in Good Society by Florence Howe Hall

I really want to host a dinner party now! I need some guests first, and a fine dress.

Where do you get these wonderful pictures? I am looking for a good resource for Edwardian period paintings in a realist style.

Hi Thomas,

A lot of my photos came from the Mary Evans Picture Library. Others are taken from books I’ve downloaded at Google Books, some I’ve scanned from books I own, and still others are borrowed from other websites.