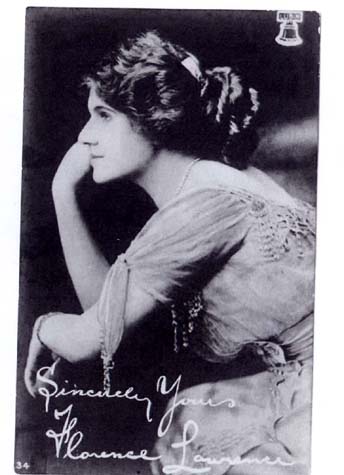

Though Mary Pickford is associated with the early days of American cinema, it was her fellow Canadian Florence Lawrence who is the first movie star. Born on New Year’s Day in 1890, the Hamilton, Ontario native entered show business at the age of four, traveling the vaudeville circuit as “Baby Flo – The Child Wonder Whistler.” Her mother, Charlotte A. Bridgwood, was a vaudeville actress known professionally as Lotta Lawrence and was both leading lady and director of the Lawrence Dramatic Company. After the death of Florence’s father in 1898, her mother moved the family–consisting of Florence and her two elder brothers–to Buffalo, New York, where Florence attended local schools and developed athletic skills, in particular horseback riding and ice-skating.

Florence continued to develop her acting talents, but like many hopeful actresses haunting the casting rooms of Broadway, success was elusive. The early years of the American cinema were both lean and abundant–lean of actors who were skeptical of this new medium (which, due to its start in cheap nickelodeons, were seen as entertainment for the poor)–and abundant in pioneers eager to enter uncharted territories and audiences eager for more movies. Florence was likely one of many unemployed young actresses who viewed the motion pictures as a last resort, but when she was cast in Daniel Boone; or, Pioneer days in America, an Edison Manufacturing Company film, it was the beginning of a marvelous career.

She portrayed Daniel Boone’s daughter, and her old riding skills came in handy as she got the part because she knew how to ride a horse. Her mother also found a role in the film, and they were each paid five dollars a day for two weeks of outdoor filming in freezing weather. In 1908, Florence went on to make 38 movies at Vitagraph, most roles given to her because of her equestrian skills. She turned briefly to the more legitimate and respectable stage, but after touring with Seminary Girls, Lawrence resolved that she would “never again lead that gypsy life.”

Her fortunes changed when a fellow Vitagraph actor, Harry Solter, sought a “a young, beautiful equestrian girl” for a D. W. Griffith production at Biograph Studios. When Lawrence learned of this opportunity, she quickly convinced Solter and Griffith she was the right actress for the part, and came to Biograph in 1908, where she earned a whopping $25 a week at a time when the average annual income was less than $500 a year. Her starring role in Griffith’s The Girl and the Outlaw was followed by starring roles in sixty-five films by 1909. She went on to marry Harry Solter, but ironically, this was when audiences began to clamor for her name. Florence, like the cinema’s other leading ladies, was known only by the name of her studio–the Biograph Girl–due to fears that film stars would demand higher salaries. But the cult of celebrity had struck the motion picture industry, and the name “Florence Lawrence” became more prominent than “Biograph Pictures.”

Now known by name, with the much-feared privileges that accompanied stardom, Florence and her husband decided to strike out on their own. They wrote to the Essanay Company to offer their services as leading lady and director, but rather than accept this offer, Essanay reported the offer to Biograph’s head office, and they were promptly fired. Now cast adrift, the Solters joined with Carl Laemmle’s Independent Moving Pictures Company of America, where Laemmle created the “star system.” In 1910, Lawrence left IMP, but not before choosing an 18 year old Mary Pickford as her successor at the company. Two years later, via a deal the Solters made with Laemmle, they formed their own studio, Victor Film Company, where they made a number of successful films before selling out to Universal Studios.

Things look promising for Florence’s career, and despite a brief period of retirement, she continued to remain the cinema’s top draw. However, tragedy struck during the making of Pawns of Destiny, when a staged fire got out of control and Florence was burned, suffered a serious fall, and fell into shock for months. She divorced Solter, blaming him for the accident, and to add to her problems, Universal refused to pay her medical expenses. She took time off to recover, but discovered that at 29, her days of stardom had ended. Subsequent comeback attempts were marred by her health and the public having moved on, and all of her screen work after 1924 would be in uncredited bit parts. Her personal life was in shambles, having divorced and remarried twice (the last husband abusing her physically), losing her mother in 1929, and the stock market crash depleting her fortunes. In 1936, sympathetic MGM gave her and other old stars small parts for seventy-five dollars a week, but alone, discouraged, and suffering with chronic pain from myelofibrosis, a rare bone marrow disease, Florence Lawrence decided to end her life.

On the 27th of December, she was found unconscious in bed in her West Hollywood apartment after she had attempted suicide by eating ant paste. She was rushed to a hospital but died a few hours later, and sadly, just nine years after she had paid for an expensive memorial for her mother, Lawrence was interred in an unmarked grave not far from her mother in the Hollywood Cemetery (now Hollywood Forever Cemetery, in Hollywood, California). Nevertheless, Florence Lawrence not only became the first motion picture star, she made an astounding 298 films between 1906 and 1936, and also invented the first turn signal for automobiles.

Further Reading:

Florence Lawrence, the Biograph Girl: America’s First Movie Star by Kelly R. Brown