Sugar production in the Caribbean has been on my mind as I work on the second Arroyo Blanco book, A Time For Desire. In it, Roberto Sandoval and Rosa Castillo, who you might remember as one of the suffragettes in A Summer for Scandal, team up against one of the land-grabbing American corporations that took over the sugar industry in the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico in the late 19th century.

—

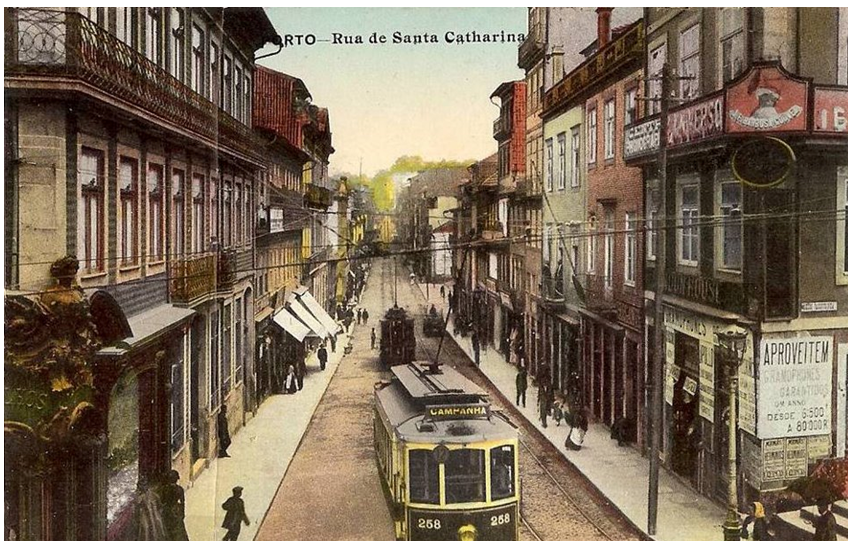

Though sugar cane was introduced to the island of Hispaniola in the early 1500s by Spanish colonists, the sugar industry in what would later become the Dominican Republic did not develop as extensively as it did in Cuba and Puerto Rico until the outbreak of two foreign wars.

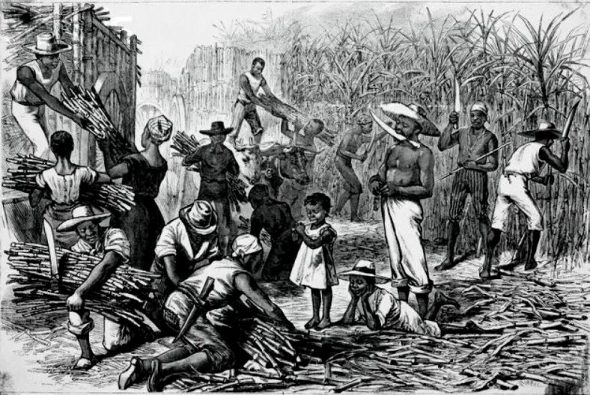

Until the mid-19th century, the Dominican sugar industry had been largely in command of criollo planters. (Criollos were the descendants of Europeans who were born in America.) Cattle ranching had been the predominant economic activity on that side of the island; during the first four hundred years of the colony, sugar cane cultivation was never as prevalent in Santo Domingo as it was in neighboring Haiti, Puerto Rico or Cuba. Various factors contributed to this, the main one being that the labor-intensive sugar production was maintained by the use of slave labor.

For decades, limited resources in the eastern half of Hispaniola discouraged the importing of slaves. Once slavery was abolished when Haitian forces assumed control of the Dominican side of the island in 1822, sugar production decreased even more.

Political instability throughout the first half of the 19th century, from the Haitian occupation of 1822 to the War of Restoration in 1865, continued to limit sugar production.

At the beginning of the 1860s, civil war broke out in the United States. The booming sugar industry of the American South was severely impacted by the conflict. As production decreased and market demand increased, greater amounts of sugar were imported from the Caribbean.

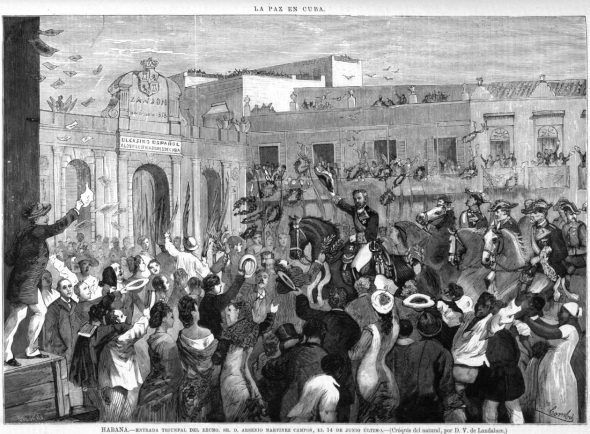

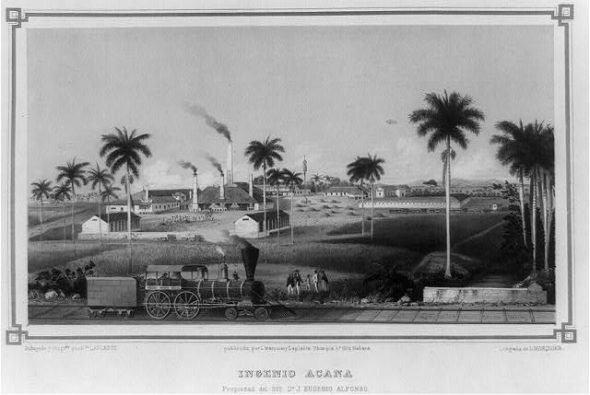

1868 marked the beginning of the Ten Years’ War in Cuba. Cuban planters fled to the neighboring Dominican Republic, where they contributed to the modernization of the sugar industry and became, along with Spanish and Italian entrepreneurs, the main investors in the revitalized industry.

By the beginning of the 20th century, traditional Dominican export crops like coffee, cacao and tobacco had been replaced by sugar. While Dominicans still cultivated sugar cane in their fields, ownership of the great sugar mills had passed to these foreign investors…and to large American corporations like the New-Jersey based South Porto Rico Sugar Company and the Connecticut-based West Indies Sugar Finance Corporation.

Aided by concessions and tax exemptions from the Dominican government, these corporations established large sugar estates in the eastern provinces. The land for these agricultural estates came from the independent farmers who’d lived in and worked on the land for generations. “By a combination of outright purchase, cajolery, tricks, threats, violence and legal maneuvers, the sugar companies easily wrestled homesites, farms and grazing land from their former holders or owners, leaving them landless and destitute,” wrote the American Bruce J. Calder 1 , who recounted how these suddenly landless peasants became dependent these sugar estates for wages.

Unemployment grew in the east, unrelieved by the corporations, who preferred to import labor from Haiti and other Caribbean islands during harvest time.

It was these displaced farmers who would take up arms against U.S. troops during the 1916 Military Occupation (caused in part by the desire to protect American sugar interests from the constant revolutions that broke out during the first decade of the 20th century), motivated largely by their resentment of the American corporations that had driven them into landlessness and poverty, as well as the brutal aggression employed by U.S. marines. As conflicts between these insurgents and marines became more frequent and bloodier, and the marines’ reprisals to revolutionaries and pacifists alike grew more violent, the displacements continued. More and more families chose to flee the east and settle in the more sparsely populated north.

It wasn’t until well after the end of the Occupation in 1924 that sugar production in the Dominican Republic returned to the hands of Dominicans…or, that is to say, one Dominican in particular, the dictator Rafael Trujillo, whose iron control over the island’s economic interests extended to the sugar industry.

- Calder, Bruce. Caudillos and Gavilleros versus the United States Marines. Duke University Press, 1978. ↩