With the declarations of War in August of 1914, the epoch alternately known as the Edwardian age, La Belle Epoque, or more ominously, fin de siècle, ended with—literally—a bang. Nearly one hundred years after its conclusion, WWI appears a preventable tragedy, or a baffling piece of history, and is mourned for the loss of “innocence” with which the long, sunny summers bathed the Edwardians. On its surface, Downton Abbey promulgates this image, though a closer look at the twists and turns of the script worries at the genial, dazzling sheen.

In reality, though war was unexpected, it was largely inevitable (Mr. Pamuk’s presence in England was not entirely for pleasure!) and when it was declared the world seemed to heave a sigh of relief and shrug its shoulders in anticipation of relieving the incredible tension built up between the Powers and its satellites stretching back to the unification of Germany in 1871! In the wake of the disastrous Franco-Prussian War (1870-71), which saw the demise of Napoleon III’s Second Empire, this bold move by Prussia disrupted the balance of power set in place during the Congress of Vienna in 1814–15, and set the stage for the diplomatic, and sometimes military tussles, of the period between 1877 and 1914, which culminated in the inescapable specter of the Great War.

And yet, society was largely ignorant of the impending conflict. The social seasons of Paris, London, New York, et al remained brilliant, and the only turmoil worrying England was domestic: militant suffragettes (though force-feedings and the “Cat and Mouse Act” forced leaders of the movement to flee imprisonment), the Irish Question, and “serious industrial unrest and an enormous increase in trade union membership, which affected all industries.” But not even the rising nationalism within the British Empire (notably in India) failed to alarm the English. Mostly, the topic of war remained unfathomable because so many believed it utterly impossible in the face of so many exciting technological advances, advances that proved the might and intelligence of mankind over its formerly primitive state (ironically, technology hastened the war and increased its deadliness—dreadnoughts, chemicals [mustard gas], submarines, airplanes, machine guns, etc). Besides, war was simply out of date!

And yet, society was largely ignorant of the impending conflict. The social seasons of Paris, London, New York, et al remained brilliant, and the only turmoil worrying England was domestic: militant suffragettes (though force-feedings and the “Cat and Mouse Act” forced leaders of the movement to flee imprisonment), the Irish Question, and “serious industrial unrest and an enormous increase in trade union membership, which affected all industries.” But not even the rising nationalism within the British Empire (notably in India) failed to alarm the English. Mostly, the topic of war remained unfathomable because so many believed it utterly impossible in the face of so many exciting technological advances, advances that proved the might and intelligence of mankind over its formerly primitive state (ironically, technology hastened the war and increased its deadliness—dreadnoughts, chemicals [mustard gas], submarines, airplanes, machine guns, etc). Besides, war was simply out of date!

Many memoirs and diaries published in the aftermath of WWI chronicled the end of their relatively peaceful era, and most expressed the contentment, confusion and disbelief of the weeks leading up to the declaration of war. That summer, the summer of 1914 was marked for its warmth and fineness, the best in living memory; the “thunderbolt, when it fell, descended from a cloudless sky.”

One morning in June, 1914, Desmond Chapman-Huston “motored in Tisbury to get petrol or something. The newspapers had not arrived before I left. As the tank was being filled I idly noted a poster which said: ‘Murder of an Austrian Archduke.’.” While Germany invaded Belgium, leaving Britain to deal with an ultimatum expiring midnight on August 3rd, “Monday, August 1st, the party broke up, some to go to Cowes for Cowes Week, I to go to Fleet to my mother for a few days…I left Fleet after luncheon; the train was crowded with Naval and Military Reservists recalled to their units by telegram…Soldiers were everywhere!”

Wilfrid Scawen Blunt’s diary offers a succinct, yet anxious picture of this tumultuous time:

30th June. — There has been another assassination, this time of the heir of the Austrian Emperor. I do not quite know how it affects the political situation.

27th July. — To-day’s papers are sensational. War seems to have begun on the Danube, and there has been rioting in Dublin, with firing on the mob and a bayonet charge, with two or three people killed and many wounded. This will bring things to a head and oblige Asquith to allow the arming of the National Volunteers if he does not throw up his cards and resign. This is an astonishing show of weakness and mismanagement. I see the Labour members are threatening a revolt from Asquith and a hundred Liberals as well if he does not withdraw the Amendment Bill and keep the Army in order.

30th July. — The crisis is worse than ever, with panic on all the Stock Exchanges of Europe and our own. Advantage is being taken of it to defer any settlement of the Irish question on the ground that all parties are of one patriotic mind, Irish as well as English, towards events abroad. This is of course absurd, but so long as the King puts his signature to the Home Rule Bill, the rest will not matter. The first shots have been fired in Servia.

31st July. — The ‘Times’ to-day has a special article in largest print recommending England to go to war in aid of France against Germany, but I do not believe in any such folly. Belgrade has been bombarded, and it is all but certain now there will be general European war, but not for us. Belloc and I differ in this. He is convinced that France is stronger than Germany. I am not. He talks of Germany as calling out to our Foreign Office to mediate. I believe Germany means war, and is rejecting Grey’s foolish intervention.

1st Aug. — There is a general panic, the London Stock Exchange closed, and the Bank rate raised to 8 per cent. Germany has sent ultimatums both to Russia and to France; general war is certain, but the ‘ Times ‘ has a letter from Norman Angell in large print to-day contradictory of its yesterday’s article. The ‘ Nation ‘ and all the Liberal papers denounce the idea of war, and I cannot believe we shall be such fools as to take part in it if we are not attacked. Italy is proclaiming neutrality ; we shall do the same.

3rd Aug. — Things are marching fast. The Germans have begun their campaign against France by seizing Luxembourg, and seem to be already in Belgium. The news of this they say reached the Cabinet while it was sitting last evening (the second in the day, and that Sunday), and united all the Ministers to resolve, it is not said what. The naval reserves are being called out.

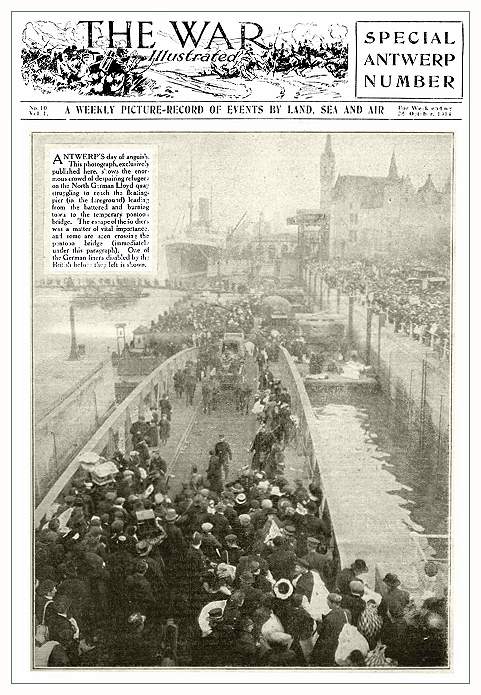

4th Aug. — Grey’s declaration turns out to be not quite what the evening papers said. It is evidently a compromise between the two opinions in the Cabinet. It denies the obligation to assist France against Germany, except to the extent of preventing bombardment by sea of the French seaboard in the Channel, but it affirms the duty of defending Belgian neutrality, and will lead us farther than the peace division think, for it must be remembered that all the action will be left in Grey’s hands at the Foreign Office, and in Winston’s at the Admiralty, and it will be easy for them to manipulate accidents into a case of necessity for despatching a land force to Antwerp. So we are not out of the wood yet. On the contrary, the British Army has been formally mobilised, and the reservists called to the colours. Our local policeman called to-day to inquire how many horses I could put up in my barns. Both Burrell and Leconfield have had a number of horses ear-marked for service, Leconfield as many as forty. I said I could put up twenty under cover, but everything connected with soldiering is hateful to me. There is talk of a British ultimatum to Germany, demanding an answer about the neutrality of Belgium being respected.

5th Aug. — The thing has been decided faster than we imagined. Yesterday Asquith announced in the Commons that Grey had sent his ultimatum to Berlin about Belgian neutrality, and had received an unsatisfactory answer, and to-day the morning papers publish “British Declaration of War against Germany.”

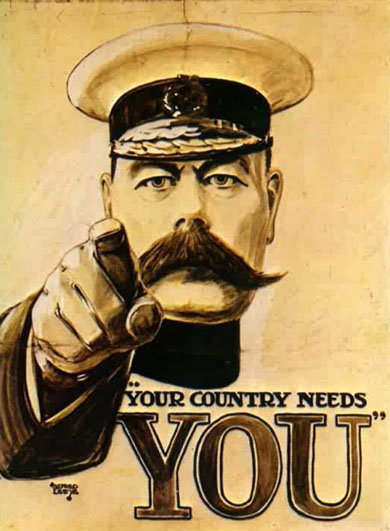

The response to this was largely patriotic. Men young and old rushed to be conscripted, their heads filled with the tales of valor and honor of warriors in the past. Public schools bred young men willing to fight for England against the tyranny of the “Hun”, for “France to be saved, Belgium righted, freedom and civilization re-won, a sour, soiled, crooked old world to be rid of bullies and crooks and reclaimed for straightness, decency, good-nature, the ways of common men dealing with common men.”

The response to this was largely patriotic. Men young and old rushed to be conscripted, their heads filled with the tales of valor and honor of warriors in the past. Public schools bred young men willing to fight for England against the tyranny of the “Hun”, for “France to be saved, Belgium righted, freedom and civilization re-won, a sour, soiled, crooked old world to be rid of bullies and crooks and reclaimed for straightness, decency, good-nature, the ways of common men dealing with common men.”

The early War poems of Kipling, Brooke, and Grenfell, expressed the ecstatic outlook of aristocratic men, which, along with reassurances that the war would be “over by Christmas” whipped up enthusiasm for enlistment. What we–and what they very quickly realized–know now is that the battle was a long, slow, and arduous slaughter, after which the vestiges of the 19th century were shelled, torpedoed, and hammered until a new society, a 20th century society, emerged from the ashes. Yet, when we continue to look at the post-WWI era, the roots of modernism stand strong in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, waiting for the right spark to bring them to fruition.

Further Reading:

The Guns of August by Barbara Tuchman

Edwardian Promenade by James Laver

Edwardian England, 1901-1914, ed by Simon Nowell-Smith

1913, an End and a Beginning by Virginia Cowles

Origins of the First World War by Gordon Martel

My Diaries, v.2, by Wilfrid Scawen Blunt

Great post Evangeline!

Thank you Elizabeth!

One thing I wondered after the episode of DA last night-why did Grantham receive a personal letter (or telegram?) that WWI was starting? Was it because he’s a member of the House of Lords?

I would say yes, though the script didn’t show Lord Grantham sitting in Parliament or taking an interest in politics.

Isn’t it interesting that the slow lead up to WW1 could be located way back into the 19th century. Even by 1910, 11, 12 and 13, when people might have been watching Germany cautiously, there didn’t seem to be any urgency about.

Yet your first witness said “I left Fleet after luncheon; the train was crowded with Naval and Military Reservists recalled to their units by telegram…Soldiers were everywhere!” Once war was declared in 1914, all hell broke loose that VERY day, it would seem!

It is interesting–and is one of my absolute favorite topics to discuss about the Edwardian era (I had to restrain myself from going overboard when writing this post, lol). People were alarmed by German militarism, and anti-German paranoia was stirred up by William Le Queux’s invasion literature, but I posit that many wanted to believe in Norman Angell’s theory espoused in his 1909 book, Europe’s Optical Illusion (that “the integration of the economies of European countries had grown to such a degree that war between them would be entirely futile, making militarism obsolete.”) despite evidence to the contrary.