The Philippine-American War (1899-1913) is one reason why the new president of the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte, has announced his “separation from the United States” and his dependence on China. “America has one too many [misdeeds] to answer for,” Duterte said. Which misdeeds? And why have we not heard of them before?

The Philippine-American War was our first great-power conquest and our first overseas insurgency. It was first time we tried to exert American authority and values abroad. (See my previous post on New Imperialism.) And this war was not a small one. It was the Edwardian Vietnam. As a percentage of the contemporary population, three times as many American soldiers died in the Philippine-American War as did in the recent Iraq War. More than three-quarters of a million Filipinos died from war and related causes, nearly 10% of the population.

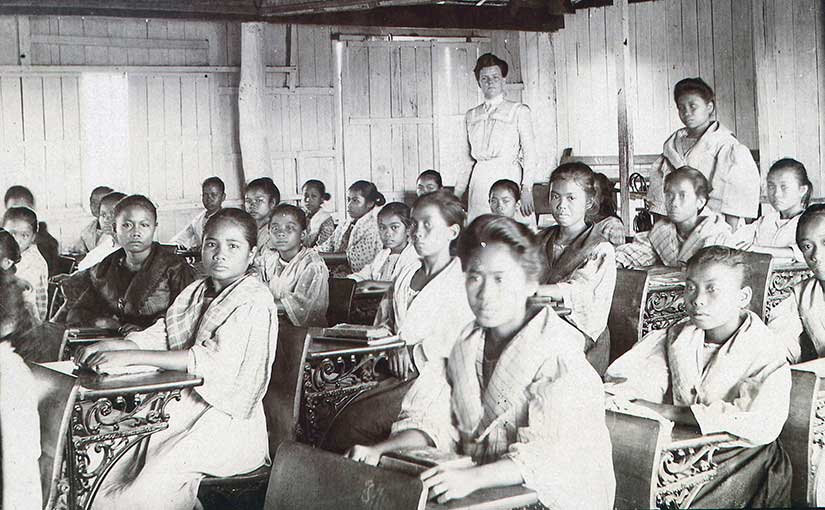

Though Duterte does not want to admit it, there were some good aspects to American rule, and some of these were the inspiration behind my own fiction writing. For example, the Americans sent 1000 schoolteachers to the islands—and not just to Manila, but to the boondocks, too. (That’s a bit of an inside joke. See, the word boondocks comes from the Filipino (Tagalog) word bundok, or mountain.) These teachers were regarded as the best American import of all, especially by the women of the islands who had been only sparingly educated by the Spanish—and that only if they were wealthy enough to afford it. In my novel Under the Sugar Sun, I reimagined one of these teachers as a Boston schoolmarm named Georgina Potter. Georgie is sent to the boondocks of Bais only to find her fiancé straying, her soldier brother missing, and the local sugar baron flirting. Adventures (and love) ensue.

There were other investments in infrastructure and human capital made by the Americans, from ports to the development of the Philippine Supreme Court. Philippine universities founded in this era have become regional attractions, particularly for their science and medical educations.

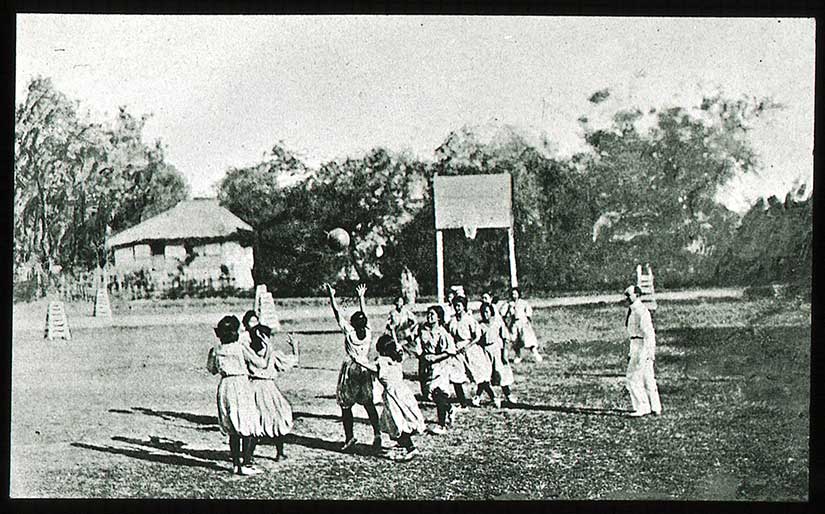

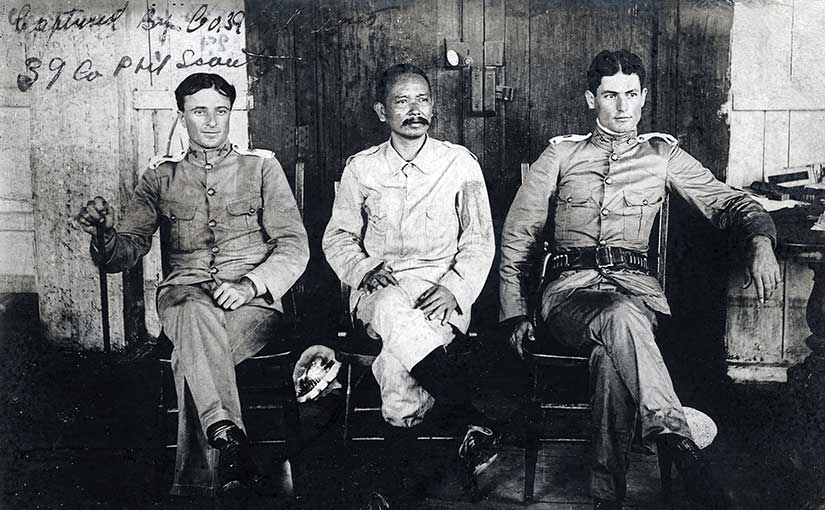

But it was not all bailes and basketball—though basketball is still wildly popular. There was also a down side to imperialism, and this appears in my books, too. The second book of the Sugar Sun series, Sugar Moon, will feature a character who survived a surprise attack at a town named Balangiga in 1901. Forty-eight Americans died there, the biggest loss for the Army since Little Big Horn. The Americans retaliated disproportionately. General Jacob “Hell Roaring Jake” Smith told his men to turn the whole island of Samar into a “howling wilderness”:

I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn, the more you kill and burn the better it will please me.

When asked the limit of age to respect, General Smith said “Ten years.” Smith declared the coasts of Samar to be “safe zones,” but anyone inland was assumed hostile to the United States and therefore a valid target. The entire island was embargoed. Cities grew crowded and diseased, and many starved. There is still a lot of debate about the number of Samareños who died in this period, with figures ranging from 2500 to 50,000. Either way, a lot.

Samar was the My Lai—or the Abu Ghraib—of the Philippine-American War. Your counterpart in 1901-1902 would have read daily reports on General Smith’s court-martial. (Yes, he was court-martialed, but only after a round-about investigation of a totally different incident.) With the advent of the trans-Pacific telegraph cable, people could follow events with an immediacy that had been previously impossible. As a result, even though General Smith received only a slap on the wrist, popular outcry in the US later forced President Roosevelt to demand the general’s retirement. Why so light still? The dirty secret was that Smith’s commanding officers wanted this “chastisement” policy because they agreed with him that “short, severe wars are the most humane in the end. No civilized war…can be carried on on a humanitarian basis.” And the leaders of the insurgency in Samar did surrender in April 1902, only seven months after the attack at Balangiga. The Americans thought the ends justified the means.

The incident that Duterte likes to talk about the most was not in Samar, though. The president is from the island of Mindanao, where the United States fought its first war against Muslim separatism. Islam was the primary Filipino religion before the arrival of the Catholic Spanish, and still today about five percent of Filipinos are Muslim. Ninety-four percent of Filipino Muslims, dubbed Moros by Spanish, still live the large southern island of Mindanao. When the Americans first arrived in the Philippines in 1898, they had enough problems on their hands with the Filipino Christians, so they made a “live and let live” agreement with the Moros. Once the rest of the islands were pacified, though, the Americans tried to extend their rule over Mindanao. They wanted to issue identity cards, collect taxes, outlaw slavery, and disarm the population.

Not all of these are bad things—I’m thinking mostly of the abolition of slavery—but to the Moros these laws struck at the heart of local autonomy. In the resulting fight, young warriors attacked anyone considered an enemy of Islam—and though they were not specifically bent on suicide, they were not afraid of death, either. They were so relentless, in fact, that the American Army had to requisition a whole new firearm, the .45-caliber—the only pistol with enough stopping power to fight Moros armed only with knives. This pistol, named the 1911 after the year it was adopted, was a standard-issue firearm until 1985, and it still remains a favorite of many in the military today.

Americans fought their largest engagements against the Moros, and this meant some of the worst massacres happened against the Moros, as well. At Bud Dajo in 1906, the Moros had retreated to the interior of an extinct volcano and were surrounded by American forces who had the high ground. Instead of a slow siege, the Americans fired down into the crater and killed 900 Moros, including women and children. Reports of the event shocked Americans at home, but it did not stop the war, which would rage on for seven more years, until 1913.

Part of the reason the Moro War stretched on so long was that it was all “chastisement” and relatively little “attraction.” In other words, there was a lot less “benevolent assimilation” here—fewer hospitals, almost no teachers, less infrastructure, and so on. Today, the Moros have the same complaint against the majority Catholic government of the Philippines—they are not getting the public works and development projects they see in the rest of the islands, but they cannot run their own affairs, either. Though part of Mindanao has been made an autonomous region, such a compromise has not brought an end to the violence. Some groups aim for legitimate political goals, some groups are professional kidnappers-for-hire, and a few are eager hangers-on of the latest Islamist terror organizations, including al Qaeda and ISIS.

Yep, those guys. Did you know the dress rehearsal for 9/11 was in the Philippines? Ramzi Yousef and Khalid Sheik Muhammad, masterminds of the 1993 and 2001 World Trade Center attacks, respectively, both operated out of the Philippines in the 1990s. The Philippine National Police thwarted an attempt of these men to fly a plane into CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia. This is why, only ten years after the Philippine Congress evicted the Americans from leased naval and air force bases in the islands, the Yanks were back. Special Forces operated continuously out of Mindanao from 2001 until 2016. Now Duterte wants the US Army out. He claims this is for the Americans’ protection, but it may also be that he wants to tone down the fighting in order to put forward a federalist plan. (There is a lot of irony in the fact that a politician known for encouraging vigilante squads wants to pursue a peaceful political solution to this conflict, but Mindanao is his home, so we’ll see.)

Rest assured: Duterte has not cut off ties with the United States. According to the Agence France-Press:

A frequent pattern following Duterte’s explosive remarks against the United States, the crime war and other hot-button issues has been for his aides or cabinet ministers to try to downplay, clarify or otherwise interpret them.

And within a few hours of Duterte’s separation remarks, his finance and economic planning secretaries released a joint statement saying the Philippines would not break ties with Western nations.

Moreover, the White House insists no one has officially asked for a change in relations. The real test will be to see if the Philippines really buys weapons from China and Russia, settles its legal dispute with China over the Spratly Islands bilaterally (cutting out the United States and United Nations), and ceases joint exercises with the US military in the South China Sea. None of these things are good for the strategic interests of the United States—but to many in the Philippines, this is exactly what they like about Duterte.

None of this is happening in a vacuum. It is more like a family dispute, where discussions and disagreements today are affected by the baggage of our shared history over the last 120 years. If we approach the news only with an eye on today and ignore the way that relationships have developed over time, we miss all the important subtext.

As Lydia San Andres pointed out last week, there is a whole century—and a whole globe—of American intervention to study. I will leave the Caribbean to her talented pen (and keyboard), but if you would like to know more about how the Philippine-American War launched the American Century, you should know that I take this show on the road!

I have an illustrated talk—“America in the Philippines: Our First Empire”—that shows how our experience in Asia fundamentally changed the U.S. role in the world and launched some of our best known political and military figures, to boot. I will tell you more about the good, the bad, and the ugly of how Americans ruled—and why, despite it all, the Filipino-American friendship has been so strong for so long. I will also show how recent stump speeches on transpacific trade, immigration, and national security are actually reprises of the early 1900s. Finally, I have a few stories of my own from living in the fabulous Philippines, many of which have shaped what and how I write. Read more and find my contact information here.

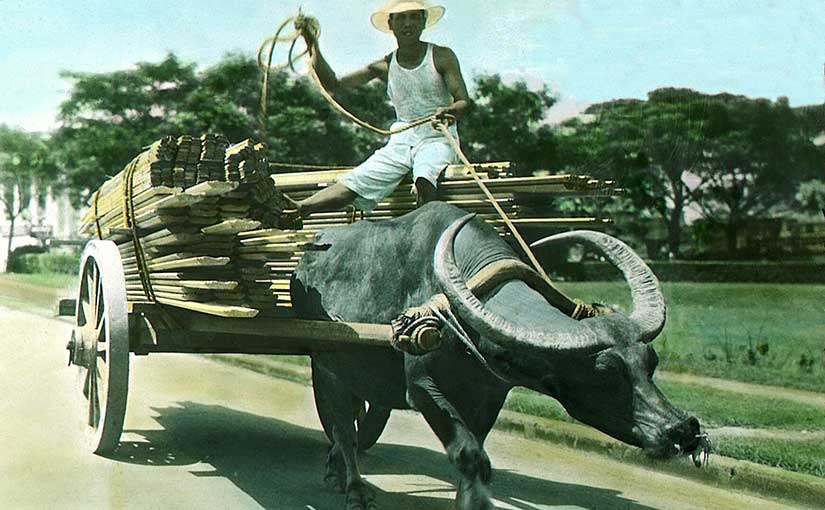

Tell your local librarian, community college, high school, veterans group, historical society, book club, or other non-profit. My talk is free to these groups…as long as I can get there. I’m not traveling by carabao, though…