Jack Ross (Gary Carr) in Downton Abbey, and the Louis Lester Band (Louis Lester is played by Chiwetel Ejiofor) in Dancing on the Edge, both give us a peek at the infiltration of not just jazz music, but black jazz musicians, into British society of the 1920s and 1930s. Though jazz music burst into mainstream Britain in 1919, with the arrival of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, the popularity of ragtime music in the Edwardian era laid the foundations for the acceptance of this syncopated music and its black (and sometimes white) musicians. During most of the First World War, Dan Kildare and his orchestra made Ciro’s nightclub the place to be for a spot of after hours fun–and drinking after curfew. Kildare, an American of Jamaican heritage, first earned his stripes in James Reese Europe’s venerable Clef Club Orchestra (the first black orchestra and first jazz musicians to play at Carnegie Hall in 1912) before taking the group–after Europe resigned to form the Tempo Club–to Joan Sawyer’s Persian Garden.

Sawyer, a popular ragtime dancer, and Kildare collaborated on the earliest ragtime-jazz recordings after James Reese Europe’s recordings–Europe directed Vernon and Irene Castle’s official band–ignited the music industry. Kildare’s success was short-lived due to the union and racial politics of the day, which penalized the many non-union black musicians playing at the nightclubs popping up across New York City. In early 1915, Dan Kildare and his orchestra sailed for England on the White Star Line’s Megantic, and made for London, where “they had a contract for a year’s engagement at the elegant new Ciro’s Restaurant.” WWI was England’s first brush with the stirrings of jazz music, which, incidentally happened almost concurrently with France’s introduction to jazz via the African-American troops attached to the French army in 1917-1918.

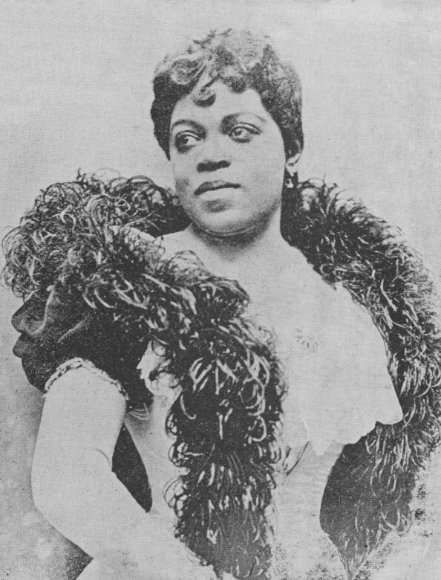

However, this was not England’s first brush with popular black performers. As early as 1903, the Williams and Walker Company’s ragtime musical, In Dahomey, smashed records on Broadway and in London’s theaterland, thus earning the company an invitation from King Edward VII for a command performance at Buckingham Palace. Other popular black entertainers of the Edwardian era included Billy McClain, Belle Davis, the Native Choir from Jamaica, and various choral groups loosely linked to the famous Fisk Jubilee Singers, to name a few. Black entertainers first brought spirituals and gospel to British audiences, then ragtime, and finally, jazz.

That said, the first jazz band to hit the mainstream, The Original Dixieland Jass Band (Jazz in 1917), was made up of white American musicians. The ODJB brought the New Orleans style jazz to prominence via recordings, and took society by storm. At the same time, the all-black Southern Syncopated Orchestra (which was made up of black Brits, West Indians, and black Americans) made serious strides in popularizing jazz music. Both bands became staples at nightclubs and private society parties, and the American-loving, very hip Prince of Wales (future Edward VIII) followed his grandfather’s suit by inviting the SSO to play at Buckingham Palace.

The jazz age, the era of the Bright Young Things, was a reaction against the slaughter of WWI and the Edwardian values that–according to the youth of the day–led to senseless war. According the Catherine Parsonage, “[i]n the 1920s, the perceived simplicity and freedom of black culture could be something desirable for whites to emulate, rather than just observe or imitate, and jazz ‘seemed to promise cultural as well as musical freedom’ for young people.” By 1926, “the Royal Albert Hall was hosting a Charleston ball, and the magazine, the Melody Maker, was actively promoting American jazz in Britain.” And by the late 1920s and early 1930s, the advent of the BBC and the increased quality of gramophone records both made jazz a bit more “respectable” (that is, acceptable in middle class drawing rooms), especially when all classes made a habit of dancing to the radio. The Prince of Wales and his brothers further led the way with the enthusiastic taking up of popular black jazz musicians and singers like Duke Ellington and Florence Mills (Mills was one of the Duke of Kent’s rumored conquests)–though aristocratic shipping heiress Nancy Cunard was considered to have taken the mingling with black entertainers a bit too far with her romantic liaison with Henry Crowder and her vocal civil rights activism.

By the closing of the Jazz Age, the music that gave the era its name had carved a place for itself in the gramophones, nightclubs, and radios of British listeners, and gave its musicians equal prominence in a time where the barriers between entertainers and Society broke away from their pre-war boundaries.

Sources

Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birth of the Recording Industry, 1890-1919 by Tim Brooks & Richard Keith Spottswood

Who’s Who of British Jazz: 2nd Edition edited by John Chilton

The Evolution of Jazz in Britain, 1880-1935 by Catherine Parsonage

Black Edwardians: Black People in Britain 1901-1914 by Jeffrey Green

A Life in Ragtime: A Biography of James Reese Europe by Reid Badger

Historical Dictionary of Anglo-American Relations by Sylvia Ellis

Harlem in Montmartre: A Paris Jazz Story Between the Great Wars by William A. Shack

Dancing on the Edge: what was life really like for black jazz bands in 1930s Britain?

WWI was indeed England’s first introduction to jazz music, but it might not have been a coincidence. In fact it seems inevitable, given France’s introduction to jazz via the African-American troops attached to the French army late in the war.

*

And I think you are spot on re the jazz age being a reaction against the senseless and useless slaughter of millions of young beautiful men during the war. If my brothers had have been obliterated in water soaked, mud filled trenches, I too would have been drinking and dancing to modern, naughty music. And my parents would have been predicting the end of civilisation as we know it.