Abroad, the English are credited with possessing a hundred religions and one sauce; but thanks to the many excellent schools of cookery which have been established of late years all over the kingdom, the latter half of the statement at any rate is now incorrect, though what was once sauce for the gander is more than ever considered sauce for the goose.

Seriously speaking, the career of cook and the pursuit of cooking as a practical art, is one of the few ways of gaining a livelihood left comparatively open to the average intelligent girl who finds herself thrown on the world at an age when a long apprenticeship or the acquirement of a regular profession are out of the question.

There is a constant and unceasing demand for good plain and high-class cooks, and this both in town and country. A methodical young lady with some knowledge of account-keeping added to her culinary knowledge can easily earn as head cook in a large establishment far move than even a well-paid literary secretary acquainted with shorthand and typewriting, and, what is more, her pecuniary value as cook will increase as the years go on, instead of diminishing, as is the case with almost every other kind of work.

Another, and to main’ a pleasanter, way of turning culinary and general knowledge to account is to take a position as teacher or lecturer under the auspices of the local School Boards and of the County Council. Tin’s opens up a sphere of agreeable work for those who possess a fair education, and the life led by a lady lecturer armed with the necessary diplomas, is infinitely freer and more agreeable than that led by a governess or companion—the more so that the teacher has much of her time to herself, part of which she is generally allowed to devote to private tuition, which sometimes takes the form, in country districts, of a demonstration lecture and a practical lesson given in the roomy kitchen of some historic country house.

It should be added, however, that the demand for cooking teachers and lecturers has lately decreased owing to the greater supply and to the fact that Board-School teachers are now qualifying themselves to add a practical and theoretical knowledge of cookery to their other subjects. Thanks to the energetic efforts of a few sensible men and women, notably the late Countess of Rosebery, the Hon. E. F. Leveson-Gower, Miss Guthrie Wright, Miss L. Stevenson, and, last but not least, Mrs. Charles Clarke, the capable and kindly Lady Superintendent of the London National Training School for Cookery, there is now no large town lacking adequate cookery tuition.

Those, especially girls, who are compelled to earn their own living, too often find themselves from the first face to face with the difficult “ways and means ” problem. But, nowadays, a certain amount of thorough training must be’ gone through before even the most practical woman can hope to obtain regular and fairly paid employment, and the time and money spent in obtaining a cooking diploma or certificate, could not, in many cases, be better laid out; while those parents who are willing to add what may, under many circumstances, prove to be an invaluable possession to their daughters’ general requirements, cannot do better than let them acquire a knowledge of, at least, good plain cookery.

Although single lessons and complete courses of tuition in special branches of cookery can be taken without any reference to time or ultimate object, it is always better to try for a certificate or diploma.

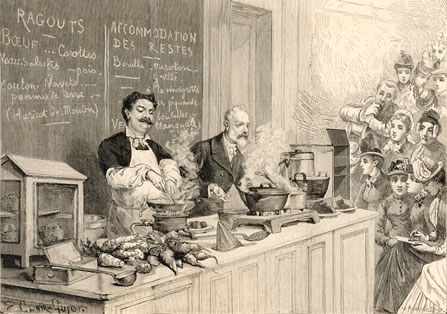

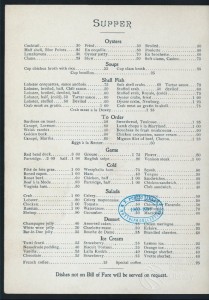

At the National Training School (now established in Buckingham Palace Road, S.W.) a Plain Cookery certificate can be obtained after five weeks’ regular attendance, and for a fee of £5 5s. In exchange for this comparatively modest sum a pupil is initiated into the mysteries of roasting and boiling meat and poultry, taught all plain sauces and gravies, and also many appetising ways of preparing cold meat. A course of soups and stews is included, as, also, twelve ways of cooking fish; some cheap dishes are added, and vegetables, pastry, puddings, sweets, cakes, breakfast dishes, and, what is, perhaps, the most important of all, a practical course of sick-room cookery.

Each pupil is expected to prepare and dish up a plain dinner of four or five courses during the five weeks of the training.

Those who wish to obtain a teacher’s diploma have a far longer and more expensive course of training to go through. No student is admitted under eighteen or over thirty-five years of age. Students must also be able to pass in common arithmetic, and their speaking, writing, and spelling will all be taken into account during the examination; for a considerable portion of a teacher’s work may lie in demonstration lectures, and clear, distinct enunciation is of importance.

Before a student is qualified for a Teacher’s diploma she must have attended the school during thirty weeks, that is seven. to eight months. The fee is £20, payable in three installments, each in advance. Pupils are only admitted on the first Monday of every month, and though the rules are few, they must be obeyed; thus, students in training are expected to be at the school every day (except Saturday) at a quarter to ten, and they seldom leave before half-past three. A medical certificate is the only excuse for absence. The above particulars not only refer to the National Training School, but apply in great measure to most of the larger provincial schools, where, however, notably, in the Edinburgh School of Cookery and Domestic Economy (3, Atholl Crescent, Edinburgh), many other subjects, such as dressmaking, knitting, plain needlework, millinery, and lectures on hygiene, are added to the cookery classes. A visit to the National Training School of Cookery is a delightful experience, especially if the tour of inspection is taken in company with the Lady Superintendent herself. Mrs. Clarke has seen pass through her hands something like fifty thousand young people, and her heart is in the work to which she has now devoted twenty years of her life.

Gas stoves play such a part in the latter-day kitchens that many mistresses of small households may like to hear that all the lessons in the National Training School are given on luminous gas stoves; a plain cookery course is often given to the general servant of some lady willing to pay the fee and put up with the temporary absence of some “household treasure” who lacks a knowledge of the culinary art to make her perfect; while not infrequently are to be found among the students young matrons turning their leisure to the best account by the acquirement of a few dainty entrees or savouries easily passed on, when once learnt, to any good plain cook.

A special feature is made of artisan cookery; and it is impossible to calculate the difference, as regards health and subsequent happiness, which would be attendant on anything like a wide dispersion of the knowledge here instilled in those students who are trained with a view to the Artisan and Household Cookery Diploma. To take but one section—that concerned with the practical knowledge of scullery work. Many a workman’s wife is, when she marries, ignorant of the best way of lighting, managing, and economising a fire; still fewer understand the regulation of heat in an oven, or the management of an open and close range. The knowledge of these and kindred matters has, as often as not, to be obtained by hard and bitter experience, and at the cost of weeks of ill-health and general discomfort.

In connection with this and certain provincial schools of cookery, lady pupils training for teachers are boarded for something like 25s. to 35s. a week. Also, day pupils can obtain their lunch on the premises. Classes for training teachers in needlework and dressmaking will be opened this month (September), the fee being £5 5s., and the time of training four months.

People not infrequently decry the value of theoretical and, if I may so style it, scientific knowledge versus acquirement of the practical side of cookery. To these the following little true story is addressed. A teacher carefully explained to a country class the mystery of game-pie making, but omitted to insist on and explain the necessity for making a hole in the crust in order that the steam and deleterious gases might escape. The receipt was faithfully worked out by some of the pupils on their return home; but, as may be imagined, they omitted this necessary item and the most disastrous results ensued. Similar instances might be multiplied indefinitely. And those who wish to really benefit to the full by any training school should make a point of attending the lectures on the chemistry of food, which include such practical subjects as the methods of preserving food, and the action of heat and of the several processes of cooking, on food.

— “How to Become a Cordon Bleu”, The Idler, by M. A. Belloc

Visit the other blogs in the hop!

- Random Bits of Fascination (Maria Grace)

- Pillings Writing Corner (David Pilling)

- Anna Belfrage

- Debra Brown

- Lauren Gilbert

- Gillian Bagwell

- Julie K. Rose

- Donna Russo Morin

- Regina Jeffers

- Shauna Roberts

- Tinney S. Heath

- Grace Elliot

- Diane Scott Lewis

- Susan Mason-Milks

- Ginger Myrick

- Helen Hollick

- Heather Domin

- Margaret Skea

- Yves Fey

- JL Oakley

- Shannon Winslow

- Evangeline Holland (you are here)

- Cora Lee

- Laura Purcell

- P. O. Dixon

- E.M. Powell

- Sharon Lathan

- Sally Smith O’Rourke

- Allison Bruning

- Violet Bedford

- Sue Millard

This was a fun share. I loved the description that the English had been accused of “possessing a hundred religions and one sauce”. Very funny.

I wasn’t able to leave a comment on your contest, by the way.

My worst disaster – I love spicy food but one day I made a chili so hot that neither my husband nor I could eat more than one spoonful and so we had to throw it away

meikleblog at gmail dot com

I don’t cook that much, so disasters are hard to remember, but last week, I made salad with Dijon mustard, and it slipped my mind that mustard is rather salty on its own, so I added both salt and mustard quite heartily… Yeah, that wasn’t such a good salad 🙂

geriths(at)gmail(dot)com

Glutenfree bread.

Oddly, it was a pumpkin pie that I had made many times before quite successfully. Guess I freaked out when my mother in law, a fabulous cook requested it for her dinner. LOL! It was soup. I tried everything to salvage it, but ended up having to start over with a run to the store even.

Thanks for the giveaway opportunity.

sophiarose1816 at gmail dot com

i don’t cook, so no disaster to share…………

My worst cooking disaster? Gosh, it’d be hard to narrow it down to one. I’m a terrible cook! Just this past weekend, I made a jello dish that I’ve made 100 times before, and it never set. It was mush! So, if I can’t even “cook” jello, there’s not much hope for me… Anyway, thanks for the great giveaway!

Susan Heim

smhparent [at] hotmail [dot] com

My worst cooking disaster involved a crumb cake recipe that did not specify pan size. I poured the batter into an 8 x 8 inch pan (seemed to fit perfectly). Unfortunately as it baked, it rose and rose and rose…. It seems 9 x 13 inches was the correct size. What came out was delicious, but the oven looked like a cake exploded in there!

I enjoy reading something that expands my knowledge – and many of the posts on this blog hop do! Yours is no exception, I leave knowing much, much more than I did when i started my read! Thanks

My worst cooking disaster was a one shared with my mother. She decided we would make Polish garlic dill pickles like Grandma did when my mom and her siblings were young. After asking Grandma how she made them we followed her instructions. Grandma used only a salt brine solution and let them ferment naturally. My mother left the jars to set on the kitchen table and then when out with her friend. While I was watching TV, I heard pops from the kitchen and went in to investigate. There were literally pickles hanging from everything and brine running down all the walls from ceiling to floor.When my mom came home I said calmly, “You better look in the kitchen!” Needless to say, that was our last attempt at making pickles. denannduvall@gmail.com