Elizabeth Robins Pennell, an American biographer, food and art critic, and traveler who settle in London with her artist husband, Joseph Pennell, had a weakness for eating, cookery, and cookbooks. By the time of her death in 1936, she had accumulated a collection of over 400 cookbooks, all of which she bequeathed to the Library of Congress.

Breakfast means many things to many men. Ask the American, and he will give as definition: “Shad, beefsteak, hash, fried potatoes, omelet, coffee, buckwheat” cakes, waffles, cornbread, and (if he be a Virginian) batter pudding, at 8 o’clock A.m. sharp.” Ask the Englishman, and he will affirm stoutly: “Tea, a rasher of bacon, dry toast, and marmalade as the clock strikes nine, or the half after.” And both, differing in detail as they may and do, are alike barbarians, understanding nothing of the first principles of gastronomy.

Seek out rather the Frenchman and his kinsmen of the Latin race. They know: and to their guidance the timid novice may trust herself without a fear. The blundering Teuton, however, would lead to perdition; for he, insensible to the charms of breakfast, does away with it altogether, and, as if still swayed by nursery rule, eats his dinner at noon—and may he long be left to enjoy it by himself! Therefore, in this, as in many other matters that cater to the higher pleasures, look to France for light and inspiration.

Upon rising—and why not let the hour vary according to mood and inclination?—forswear all but the petit déjeuner: the little breakfast of coffee and rolls and butter. But the coffee must be of the best, no chicory as you hope for salvation; the rolls must be crisp and light and fresh, as they always are in Paris and Vienna; the butter must be pure and sweet. And if you possess a fragment of self-respect, enjoy this petit déjeuner alone, in the solitude of your chamber. Upon the early family breakfast many and many a happy marriage has been wrecked; and so be warned in time.

At noon once more is man fit to meet his fellow-man and woman. Appetite has revived. The day is at its prime. By every law of nature and of art, this, of all others, is the hour that calls to breakfast.

When soft rains fall, and winds blow milder, and bushes in park or garden are sprouting and spring is at hand, grace your table with this same sweet promise of spring. Let rosy radish give the touch of colour to satisfy the eye, as chairs are drawn in close about the spotless cloth: the tiny, round radish, pulled in the early hours of the morning, still in its first virginal purity, tender, sweet, yet peppery, with all the piquancy of the young girl not quite a child, not yet a woman. In great bunches, it enlivens every stall at Covent Garden, and every greengrocer’s window; on the breakfast table it is the gayest poem that uncertain March can sing. Do not spoil it by adding’ other h’ors d’œuvres; nothing must be allowed to destroy its fragrance and its savour. Bread and butter, however, will serve as sympathetic background, and enhance rather than lessen its charm.

Vague poetic memories and aspirations stirred within you by the dainty radish, you will be in fitting humour for œufs aux saucissons [eggs with sausages], a dish, surely, invented by the Angels in Paradise. There is little earthly in its composition or flavour; irreverent it seems to describe it in poor halting words. But if language prove weak, intention is good, and should others learn to honour this priceless delicacy, then will much have been accomplished. Without more ado, therefore, go to Benoist’s, and buy the little truffled French sausages which that temple of delight provides. Fry them, and fry half the number of fresh eggs. Next, one egg and two sausages place in one of those irresistible little French baking-dishes, dim green or golden brown in colour, and, smothering them in rich wine sauce, bake, and serve—one little dish for each guest. Above all, study well your sauce; if it fail, disaster is inevitable; if it succeed, place laurel leaves in your hair, for you will have conquered. “A woman who has mastered sauces sits on the apex of civilisation.”

Without fear of anti-climax, pass suavely on from œufs aux saucissons to rognons sautés [sauteed kidneys]. In thin elegant slices your kidneys should be cut, before trusting them to the melted butter in the frying pan; for seasoning, add salt, pepper, and parsley; for thickening, flour; for strength, a tablespoonful or more of stock; for stimulus, as much good claret; then eat thereof and you will never repent.

Dainty steps these to prepare the way for the breakfast’s most substantial course, which, to be in loving sympathy with all that has gone before, may consist of côtelettes de mouton au naturel [plain mutton chops]. See that the cutlets be small and plump, well trimmed, and beaten gently, once on each side, with a chopper cooled in water. Dip them into melted butter, grill them, turning them but once that the juice may not be lost, and thank kind fate that has let you live to enjoy so delicious a morsel. Pommes de terre sautées [fried potatoes] may be deemed chaste enough to appear —and disappear—at the same happy moment.

With welcome promise of spring the feast may end as it began. Order a salad to follow: cool, quieting, encouraging. When in its perfection cabbage lettuce is to be had, none could be more submissive and responsive to the wooing of oil and vinegar. Never forget to rub the bowl with onion, now in its first youth, ardent but less fiery than in the days to come, strong but less imperious. No other garniture is needed. The tender green of the lettuce leaves will blend and harmonise with the anemones and tulips, in old blue china or dazzling crystal, that decorate the table’s centre; and though grey may be the skies without, something of May’s softness and June’s radiance will fill the breakfast-room with the glamour of romance.

What cheese, you ask? Suisse, of course. Is not the month March? Has not the menu, so lovingly devised, sent the spring rioting through your veins? Suisse with sugar, and prolong the sweet dreaming while you may. What if work you cannot, after thus giving the reins to fancy and to appetite? At least you will have had your hour of happiness. Breakfast is not for those who toil that they may dine; their sad portion is the mid-day sandwich.

Wine should be light and not too many. The true epicure will want but one, and he may do worse than let his choice fall upon Graves, though good Graves, alas! is not to be had for the asking. Much too heavy is Burgundy for breakfast. If your soul yearns for red wine, be aristocratic in your preferences, and, like the Stuarts, drink Claret—a good St. Estéphe or St. Julien.

Coffee is indispensable, and what is true of coffee after dinner is true as well of coffee after breakfast. Have it of the best, or else not at all. For liqueur, one of the less fervent, more maidenly varieties, Maraschino, perhaps, or Prunelle, but make sure it is the Prunelle, in stone jugs, that comes from Chalon-sur-Saone. Bring out the cigarettes—not the Egyptian or Turkish, with suspicion of opium lurking in their fragrant recesses—but the cleaner, purer Virginian. Then smoke until, like the Gypsy in Lenau’s ballad, all earthly trouble you have smoked away, and you master the mysteries of Nirvana.

— The Feasts of Autolycus: The Diary of a Greedy Woman (1900)

Sounds better than my breakfast, that’s for sure.

I got hungry creating this post, LOL. Actually ate a real breakfast instead of reheated leftovers!

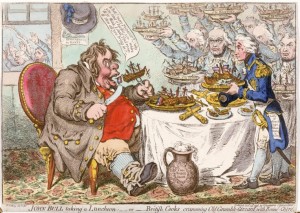

The Edwardian waistline must have been very difficult to manage. I recall that Edward VIi had the custom of weighing-in his guests at Sandringham weekends by having each sit in a weighing-chair used for jockeys. Then, as each left, they were invited to weigh-out. Now that’s some discipline, I suppose.

Fascinating anecdote!

It’s funny that Edward VII would do this–perhaps that’s why his circle called him “Tum-Tum” behind his back!

What a “flowery” approach to eating! 🙂 This was charming.

Yes! I love reading ERP for her luscious descriptions of food.