Why sigh if summer be done, and already grey skies, like a pall, hang over fog-choked London town? The sun may shine, wild winds may blow, but every evening brings with it the happy dinner hour. With the autumn days foolish men play at being pessimists, and talk in platitudes of the cruel fall of the leaf and death of love. And what matter? May they not still eat and drink? May they not still know that most supreme of all joys, the perfect dish perfectly served? Small indeed is the evil of a broken heart compared to a coarsened palate or disordered digestion.

“Therefore have we cause to be merry!—and to cast away all care.” Autumn has less to distract from the pleasure that never fails. The glare of foolish sunlight no longer lures to outdoor debauches, the soft breath of the south wind no longer breathes hope of happiness in Arcadian simplicity. We can sit in peace by our fireside, and dream dreams of a long succession of triumphant menus. The touch of frost in the air is as a spur to the artist’s invention; it quickens ambition, and stirs to loftier aspiration. The summer languor is dissipated, and with the re-birth of activity is re-awakened desire for the delicious, the piquante, the fantastic.

Let an autumn dinner then be created! dainty, as all art must be, with that elegance and distinction and individuality without which the masterpiece is not. Strike the personal note; forswear commonplace.

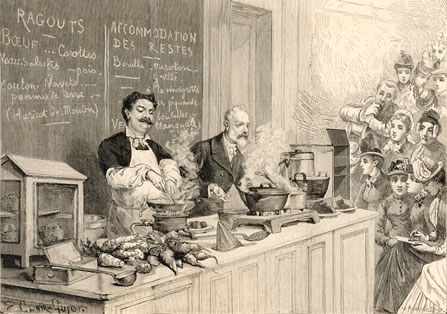

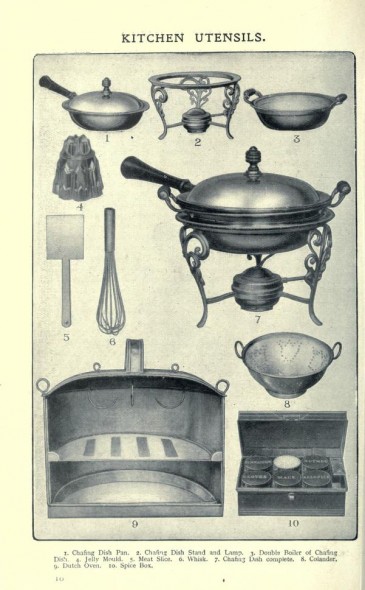

The glorious, unexpected overture shall be soupe aux moules. For this great advantage it can boast: it holds the attention not only in the short—all too short—moment of eating, but from early in the morning of the eventful day; nor does it allow itself to be forgotten as the eager hours race on. At eleven—and the heart leaps for delight as the clock strikes—the pot-au-feu is placed upon the fire; at four, tomatoes and onions—the onions white as the driven snow—communing in all good fellowship in a worthy saucepan follow; and at five, after an hour’s boiling, they are strained through a sieve, peppered, salted, and seasoned. And now is the time for the mussels, swimming in a sauce made of a bottle of white wine, a bouquet-garni, carrot, excellent vinegar, and a glass of ordinary red wine, to be offered up in their turn, and some thirty minutes will suffice for the ceremony. At this critical point, bouillon, tomatoes, and mussels meet in a proper pot well rubbed with garlic, and an ardent quarter of an hour will consummate the union. As you eat, something of the ardour becomes yours, and in an ecstasy the dinner begins.

Sad indeed would it prove were imagination exhausted with so promising a prelude. Each succeeding course must lead to new ecstasy, else will the dinner turn out the worst of failures. In turbot au gratin, the ecstatic possibilities are by no means limited. In a chaste silver dish, make a pretty wall of potatoes, which have been beaten to flour, enlivened with pepper and salt, enriched with butter and cream—cream thick and fresh and altogether adorable—seasoned with Parmesan cheese, and left on the stove for ten minutes, neither more nor less; let the wall enclose layers of turbot, already cooked and in pieces, of melted butter and of cream, with a fair covering of breadcrumbs; and rely upon a quick oven to complete the masterpiece.

After so pretty a conceit, where would be the poetry in heavy joints or solid meats? Ris de veau aux truffes surely would be more in sympathy; the sweetbreads baked and browned very tenderly, the sauce fashioned of truffles duly sliced, marsala, lemon juice, salt and paprika, with a fair foundation of benevolent bouillon. And with so exquisite a dish no disturbing vegetable should be served.

And after? If you still hanker for the roast beef and horseradish of Old England, then go and gorge yourself at the first convenient restaurant. Would you interrupt a symphony that the orchestra might play ” God save the Queen”? Would you set the chorus in “Atalanta in Calydon” to singing odes by Mr. Alfred Austen? There is a place for all things, and the place for roast beef is not on the ecstatic menu. Grouse, rather, would meet the diner’s mood— grouse with memories of the broad moor and purple heather. Roast them at a clear fire, basting them with maternal care. Remember that they, as well as pheasants and partridges, should “have gravy in the dish and bread-sauce in a cup.” Their true affinity is less the vegetable, however artistically prepared, than the salad, serenely simple, that discord may not be risked. Not this the time for the bewildering macédoine, or the brilliant tomato. Choose, instead, lettuce; crisp cool Romaine by choice. Sober restraint should dignify the dressing; a suspicion of chives may be allowed; a sprinkling of well-chopped tarragon leaves is indispensable. Words are weak to express, but the true poet strong to feel the loveliness now fast reaching its climax.

It is autumn, the mood is fantastic: a sweet, if it tend not to the vulgarity of heavy puddings and stodgy pies, will introduce an amusing, a sprightly element. Omelette soufflée claims the privilege. But it must be light as air, all but ethereal in substance, a mere nothing to melt in the mouth like a beautiful dream. And yet in melting it must yield a flavour as soft as the fragrance of flowers, and as evanescent. The sensation must be but a passing one that piques the curiosity and soothes the excited palate. A dash of orange-flower water, redolent of the graceful days that are no more, another of wine from Andalusian vineyards, and the sensation may be secured.

By the law of contrasts the vague must give way to the decided. The stirring, glorious climax after the brief, gentle interlude, will be had in canapé des olives farcies, the olives stuffed with anchovies and capers, deluged with cayenne, prone on their beds of toast and girded about with astonished watercress.

Fruit will seem a graceful afterthought; pears all golden, save where the sun, a passionate lover, with his kisses set them to blushing a rosy red; grapes, purple and white and voluptuous; figs, overflowing with the exotic sweetness of their far southern home; peaches, tender and juicy and desirable. To eat is to eschew all prose, to spread the wings of the soul in glad poetic flight. What matter, indeed, if the curtains shut out stormy night or monstrous fog?

Rejoice that no blue ribbon dangles unnecessarily and ignominiously at your buttonhole. Wine, rich wine to sing in the glass with “odorous music,” the autumn dinner demands. Burgundy, rich red Burgundy, it should be; Beaune or Pomard as you will, to fire the blood and set the fancy free. And let none other but yourself warm it; study its temperature as the lover might study the frowns and smiles of his beloved. And the Burgundy will make superfluous Port and Tokay, and all the dessert wines, sweet or dry, which unsympathetic diners range before them upon the coming of the fruit.

Drink nothing else until wineglass be pushed aside for cup of coffee, black and sweet of savour, a blend of Mocha and Mysore. Rich, thick, luxurious, Turkish coffee would be a most fitting epilogue. But then, see that you refuse the more frivolous, feminine liqueurs. Cognac, old and strong-hearted, alone would meet the hour’s emotions—Cognac, the gift of the gods, the immortal liquid. Lean back and smoke in silence, unless speech, exchanged with the one kind spirit, may be golden and perfect as the dinner.

— The Feasts of Autolycus: The Diary of a Greedy Woman by Elizabeth Robins Pennell

What a poetic writer this woman was. It really put me into the atmosphere of the age.